Upekkha

Hahnemuhle Fine Art Pearl 285 grm

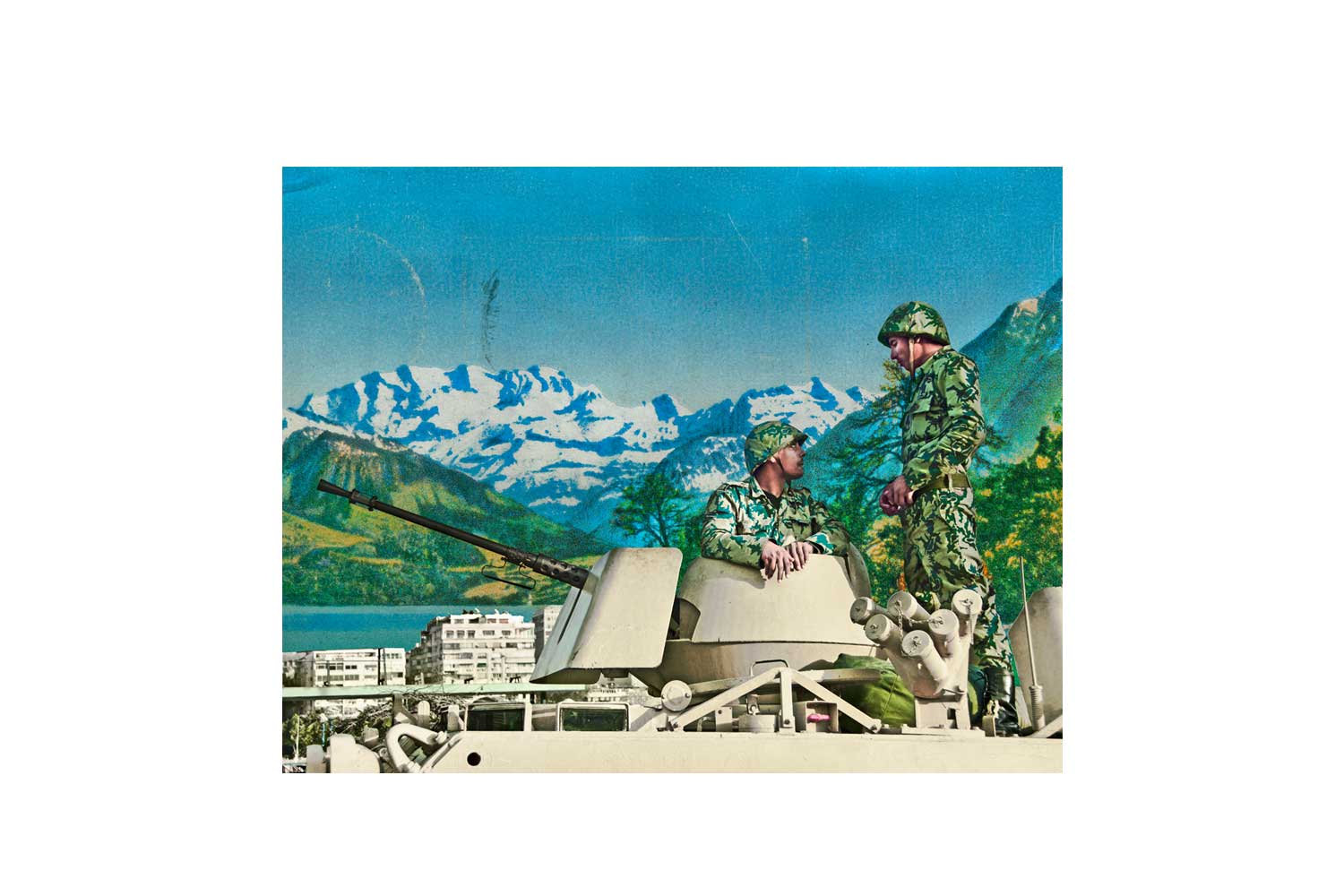

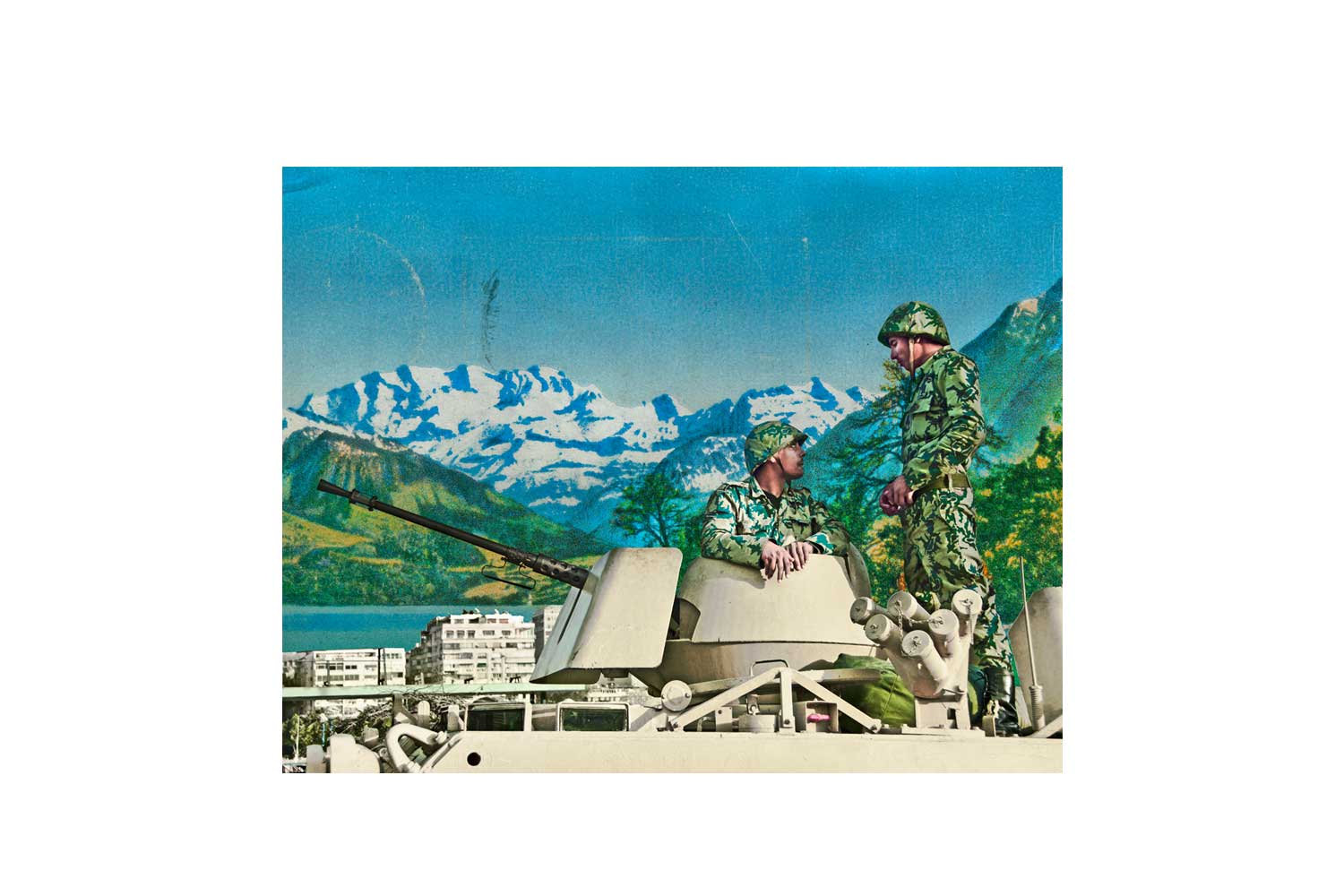

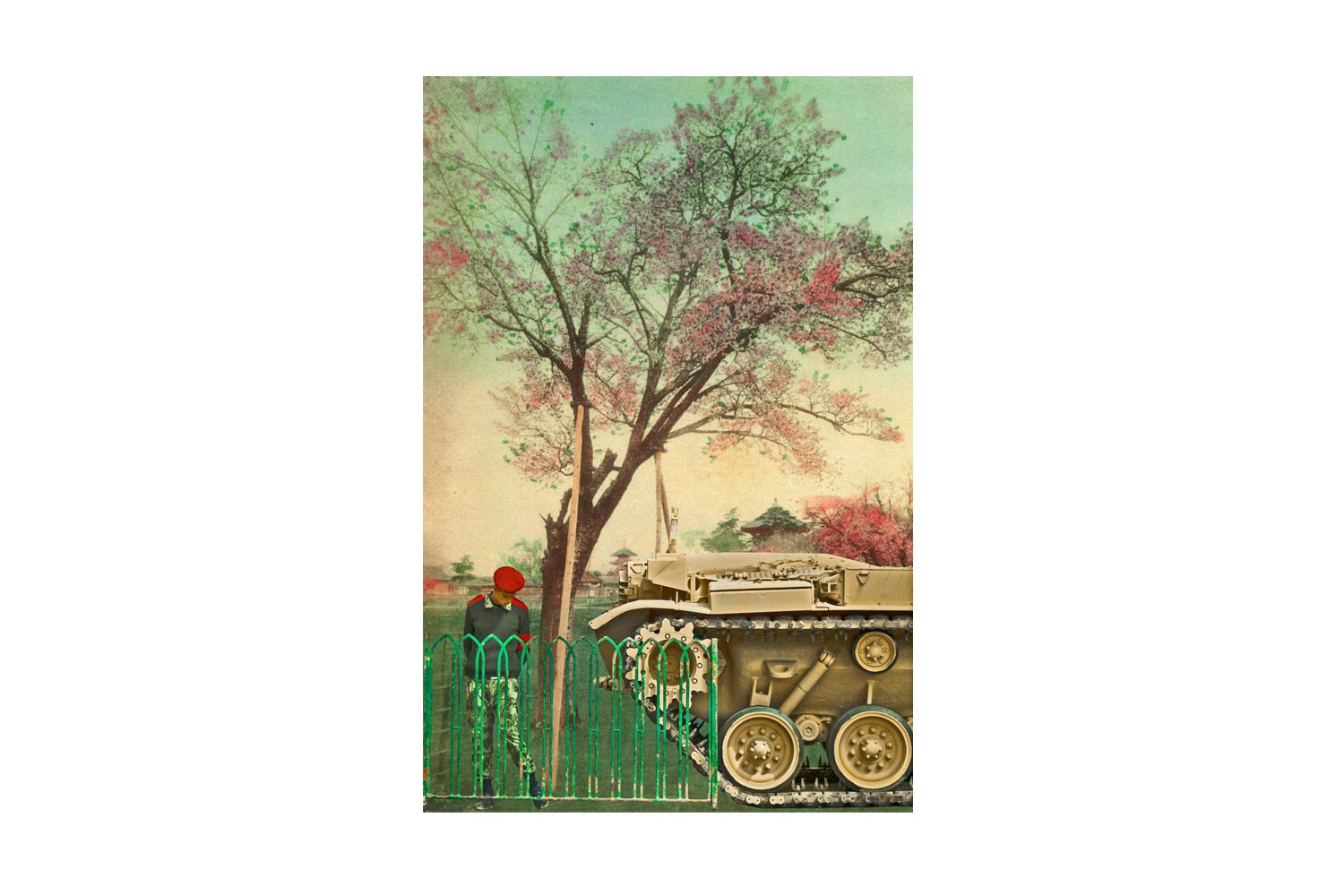

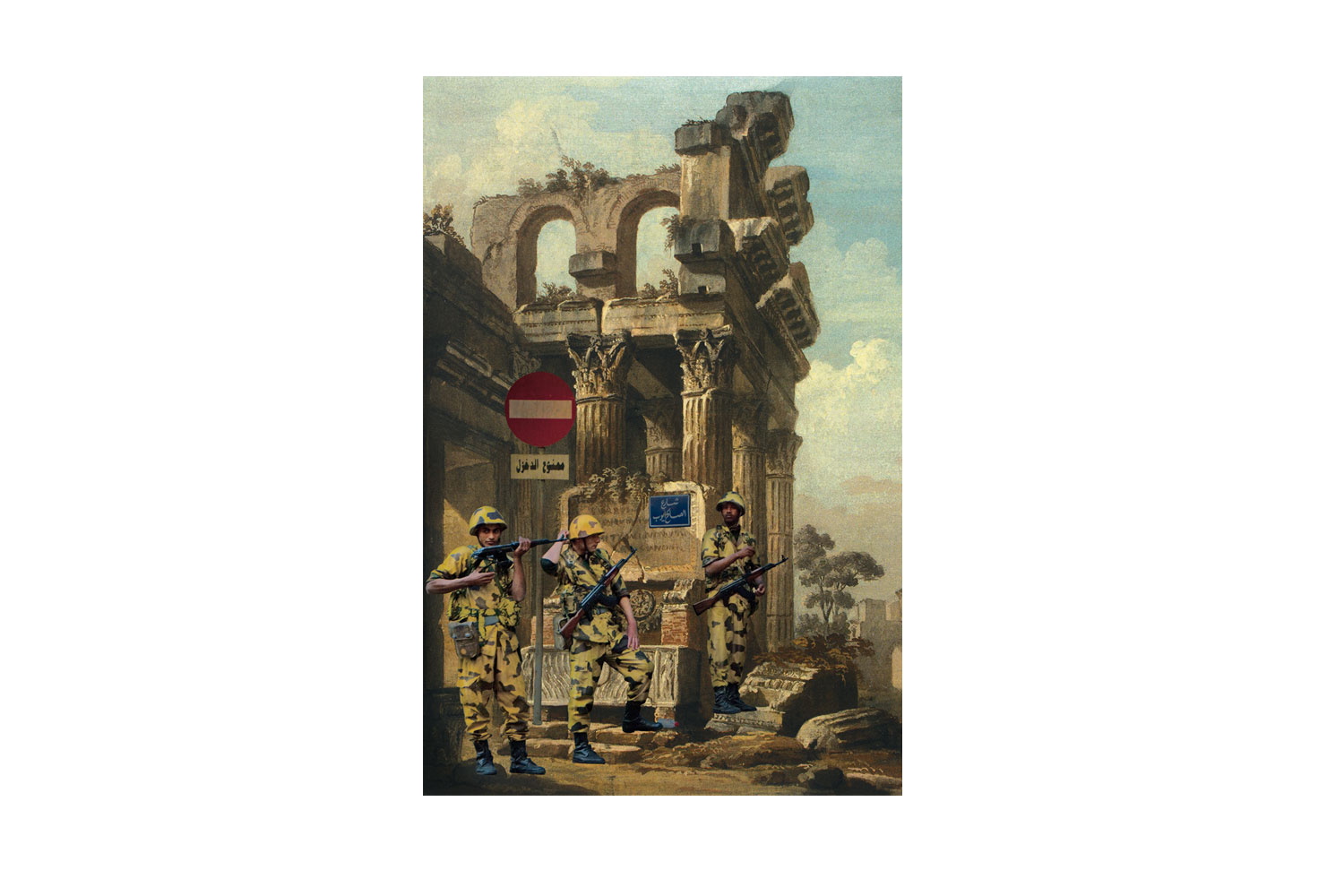

During Egypt’s January revolution we heard with apprehension that the army was on its way. This mythical force was leaving its barracks in the desert and joining citizens in Tahrir Square. And then they came, descending upon us in the square, cumbersome tanks screeching through Cairo’s desolate streets where, only days before, there had been bustle and congestion.

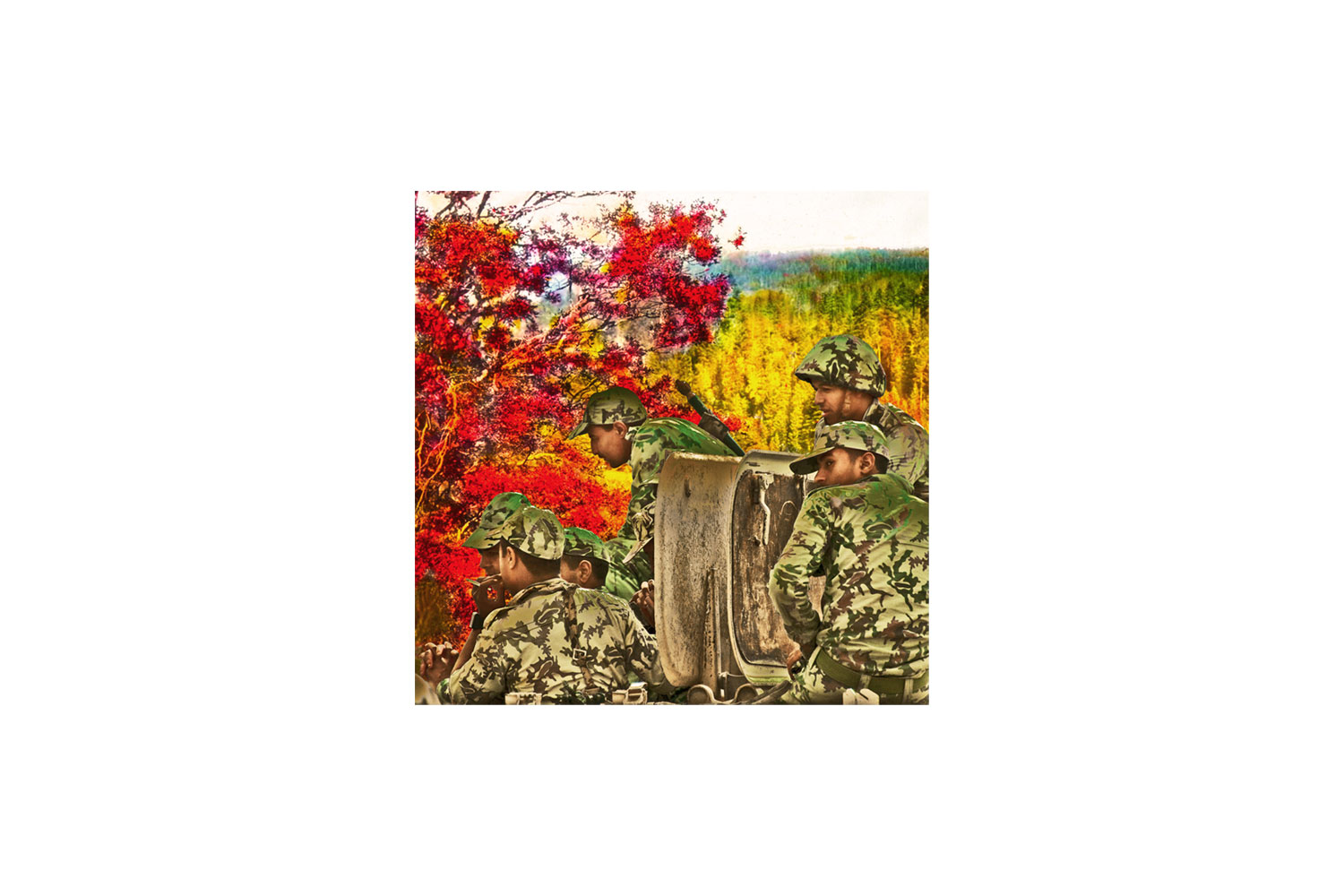

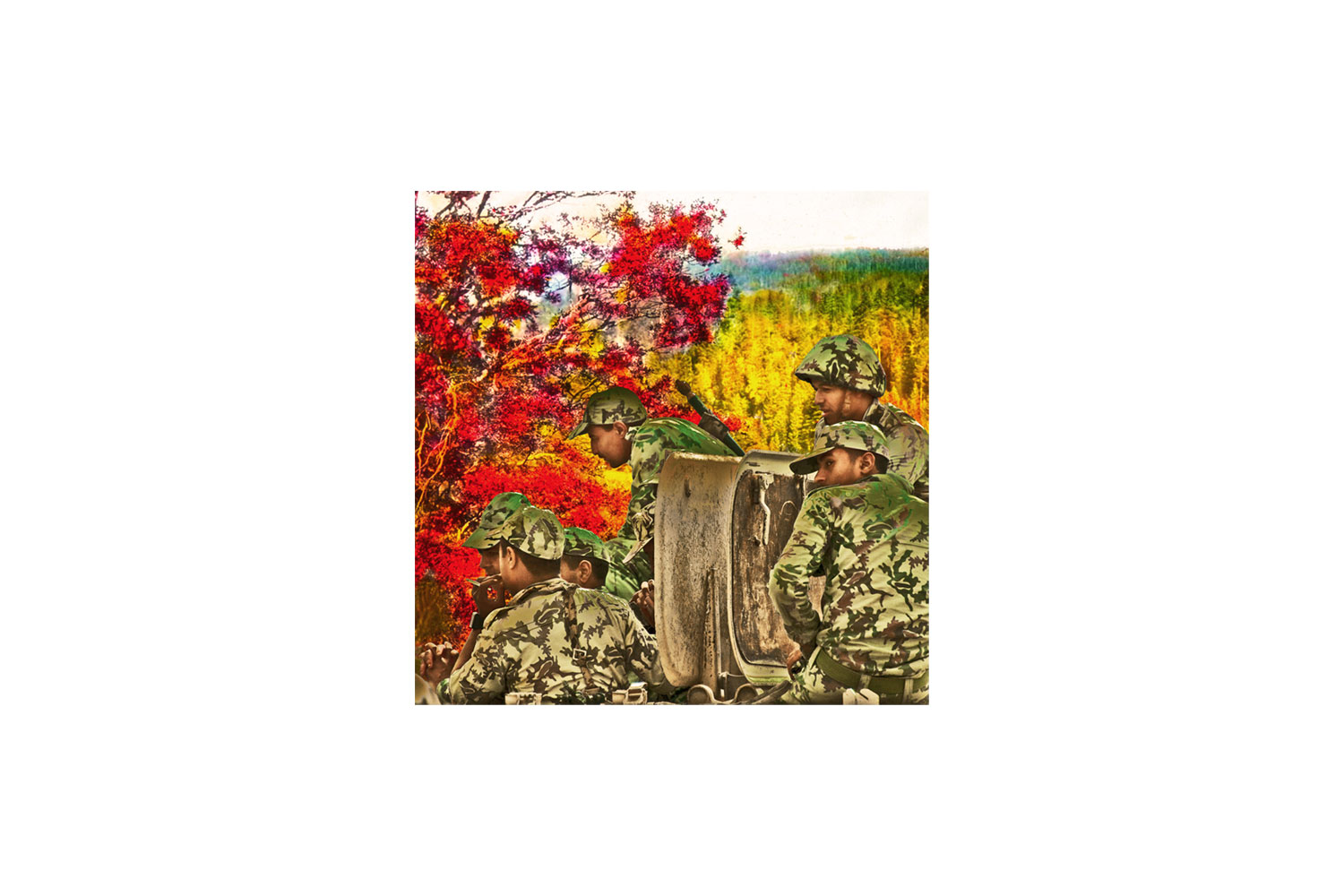

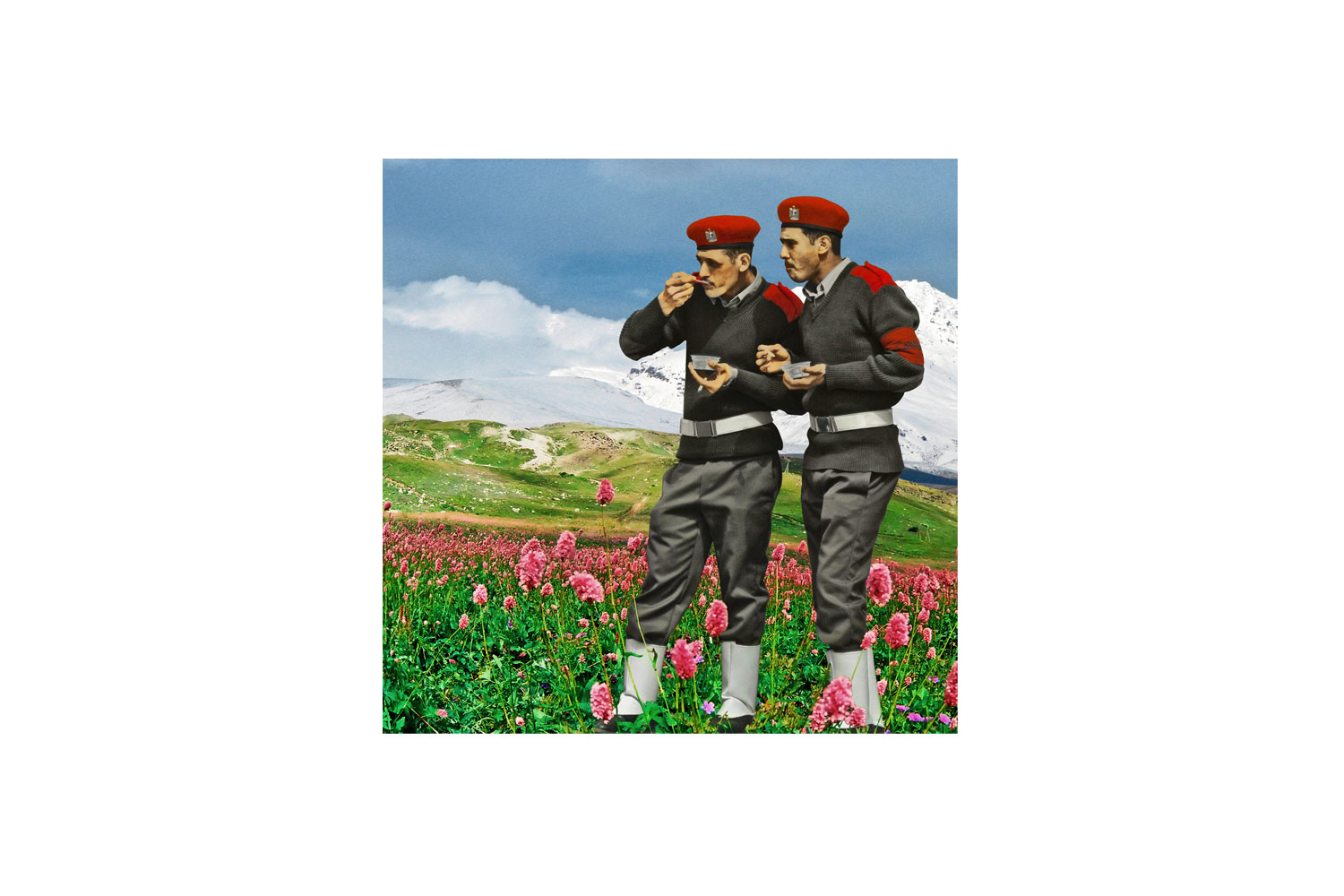

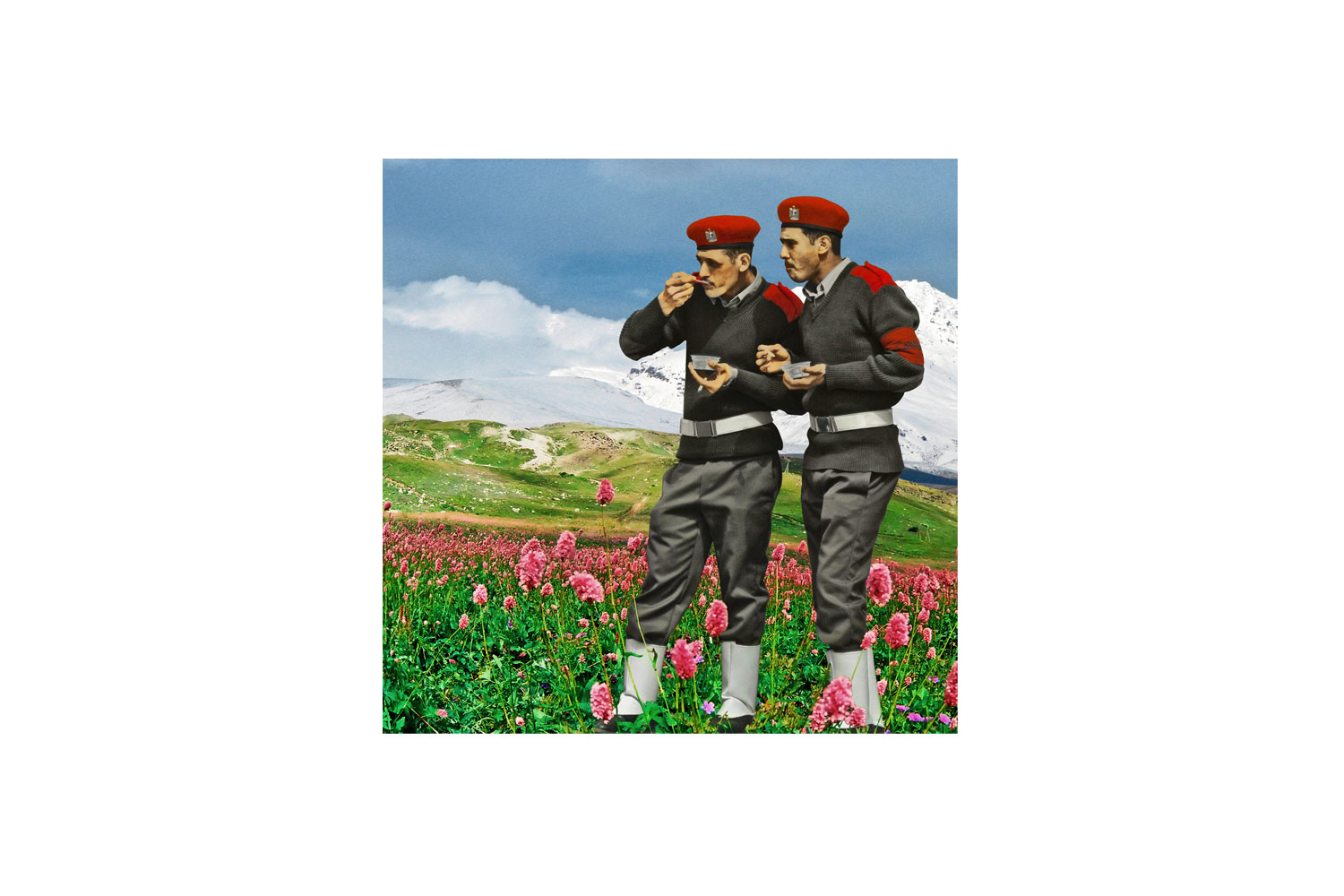

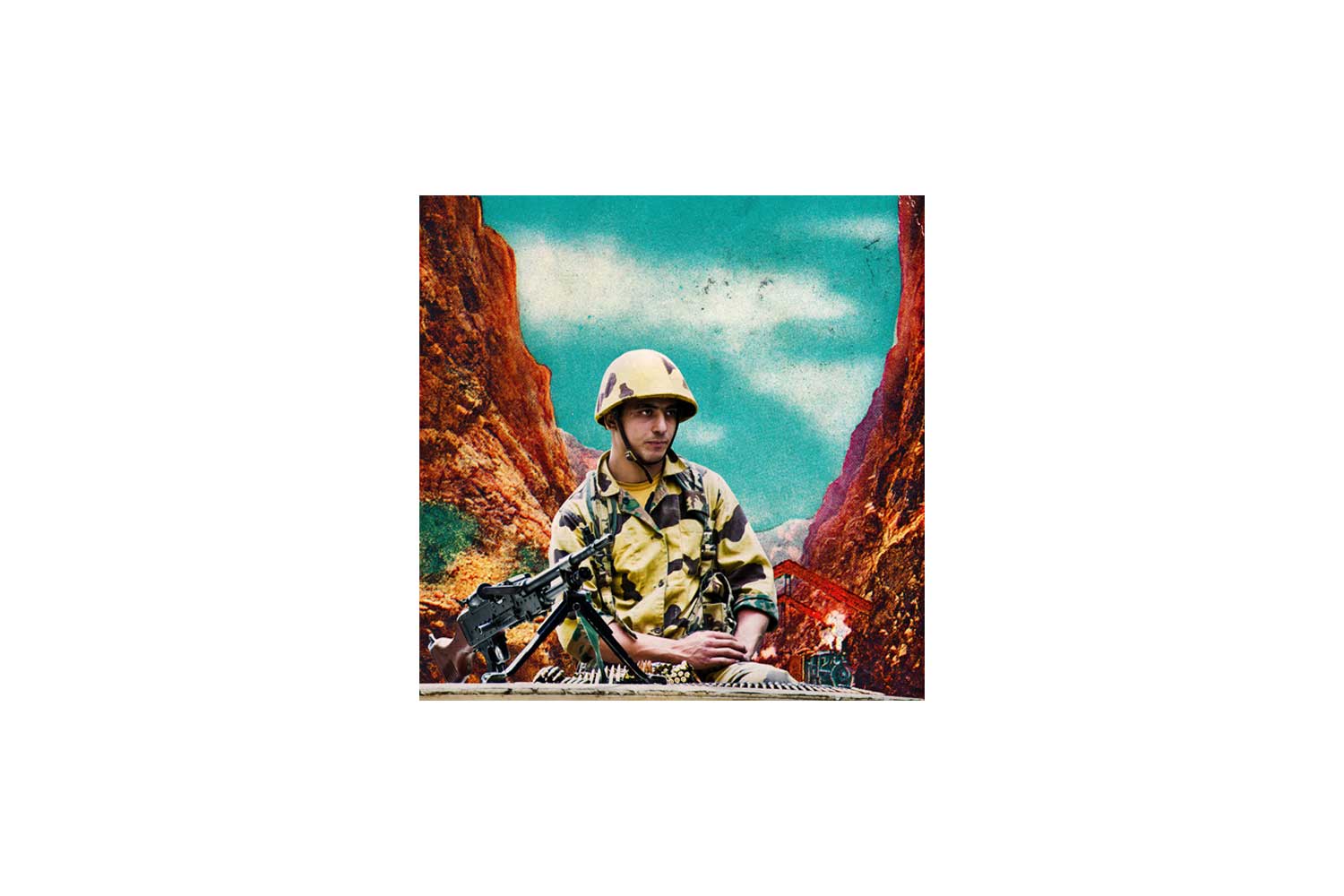

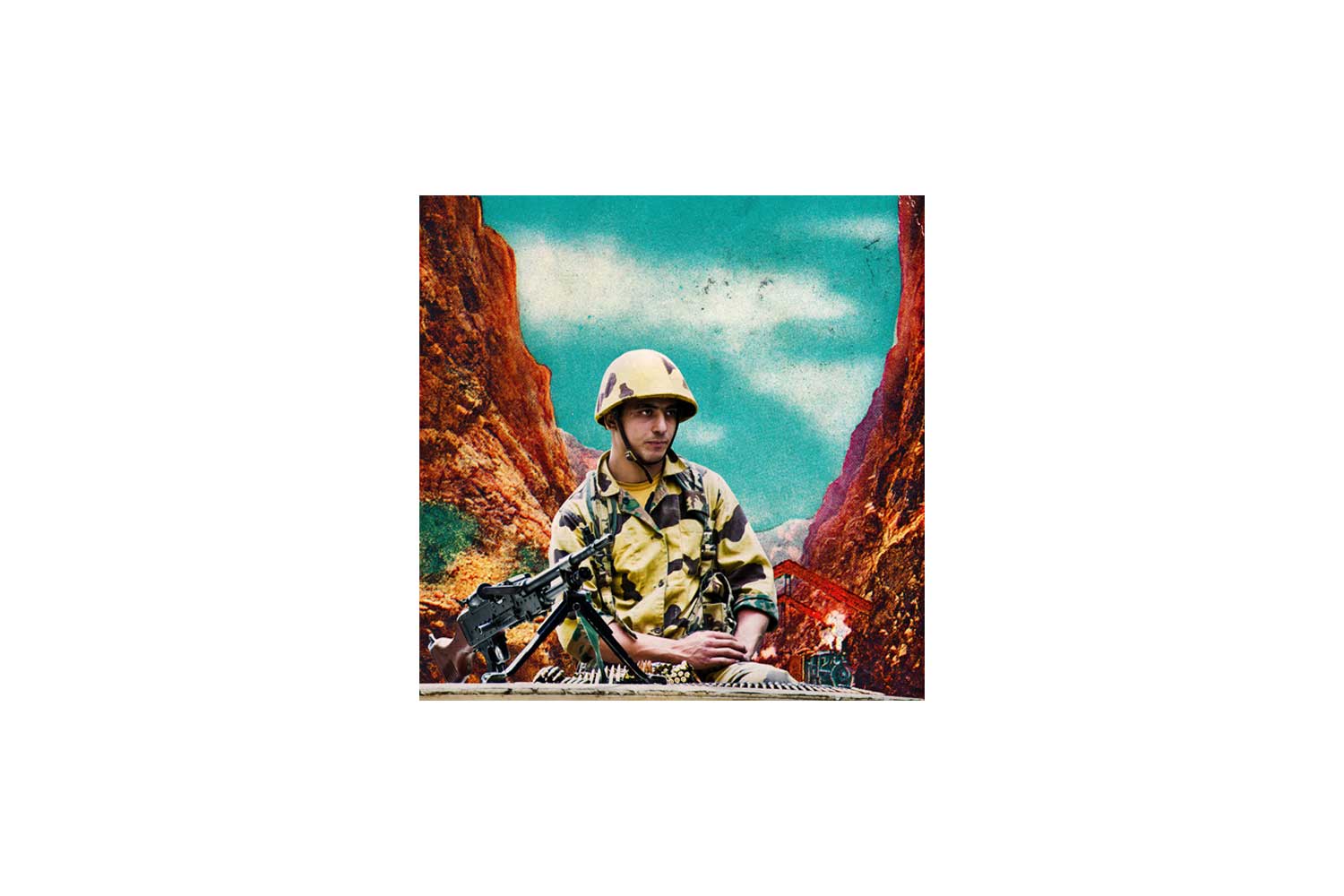

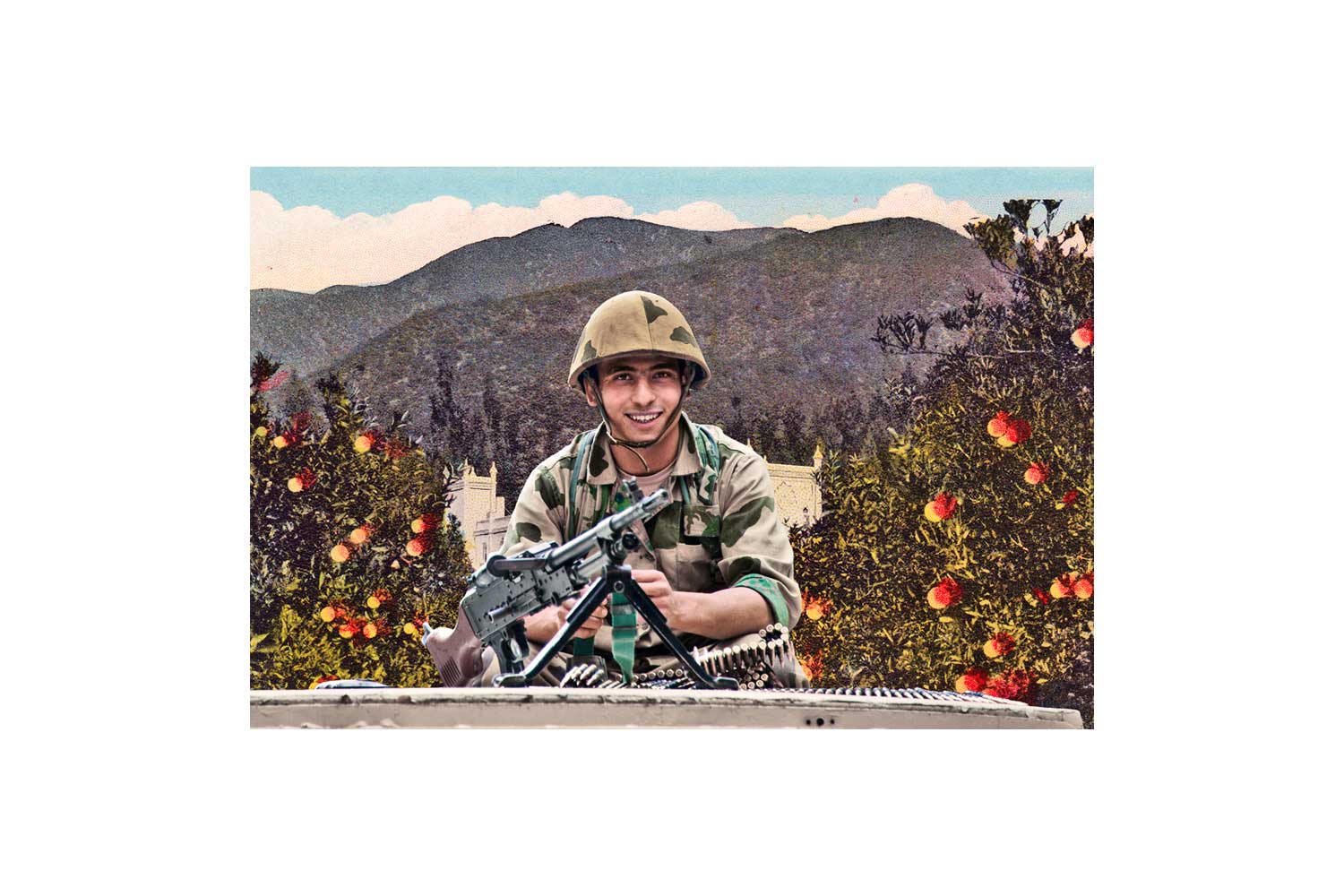

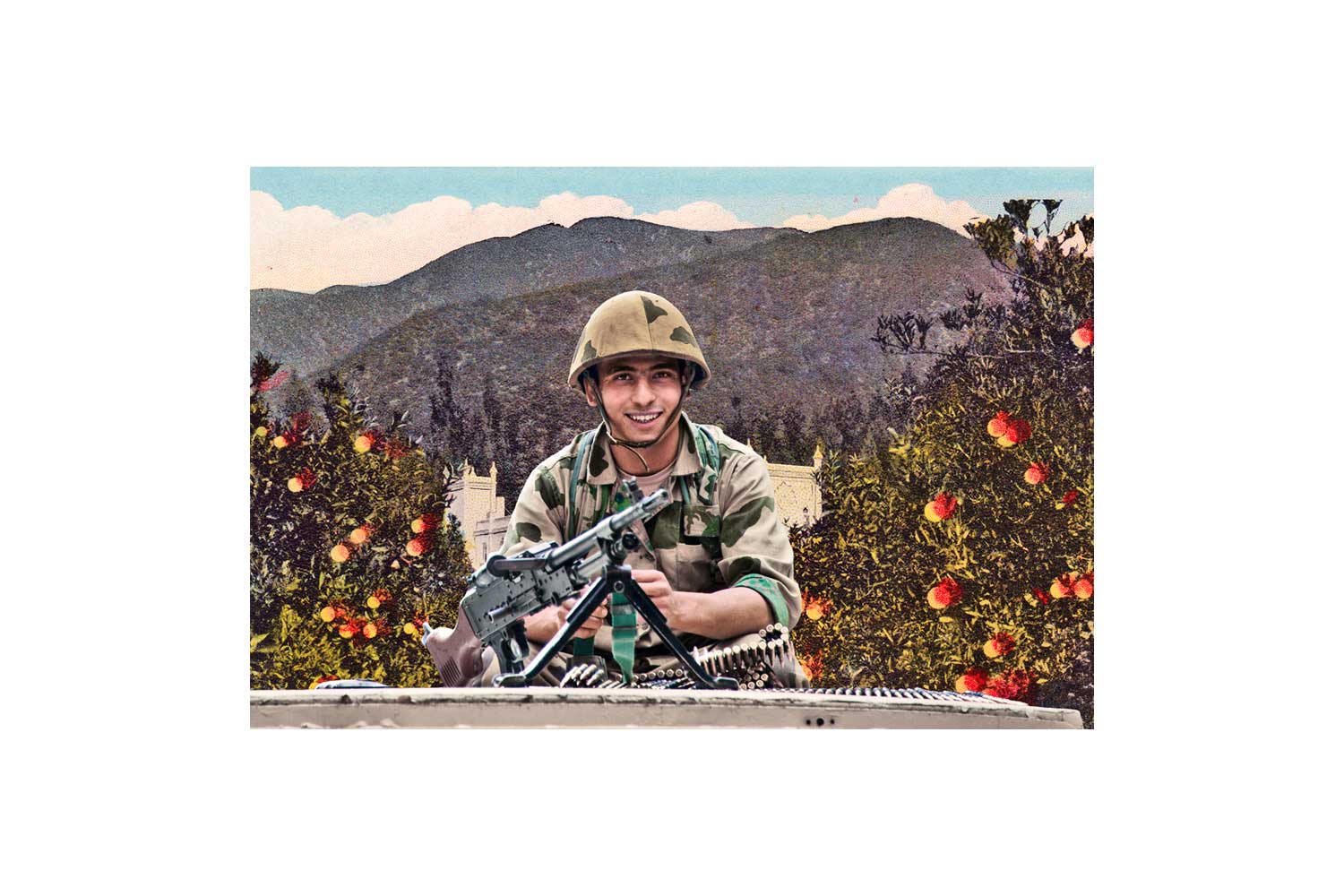

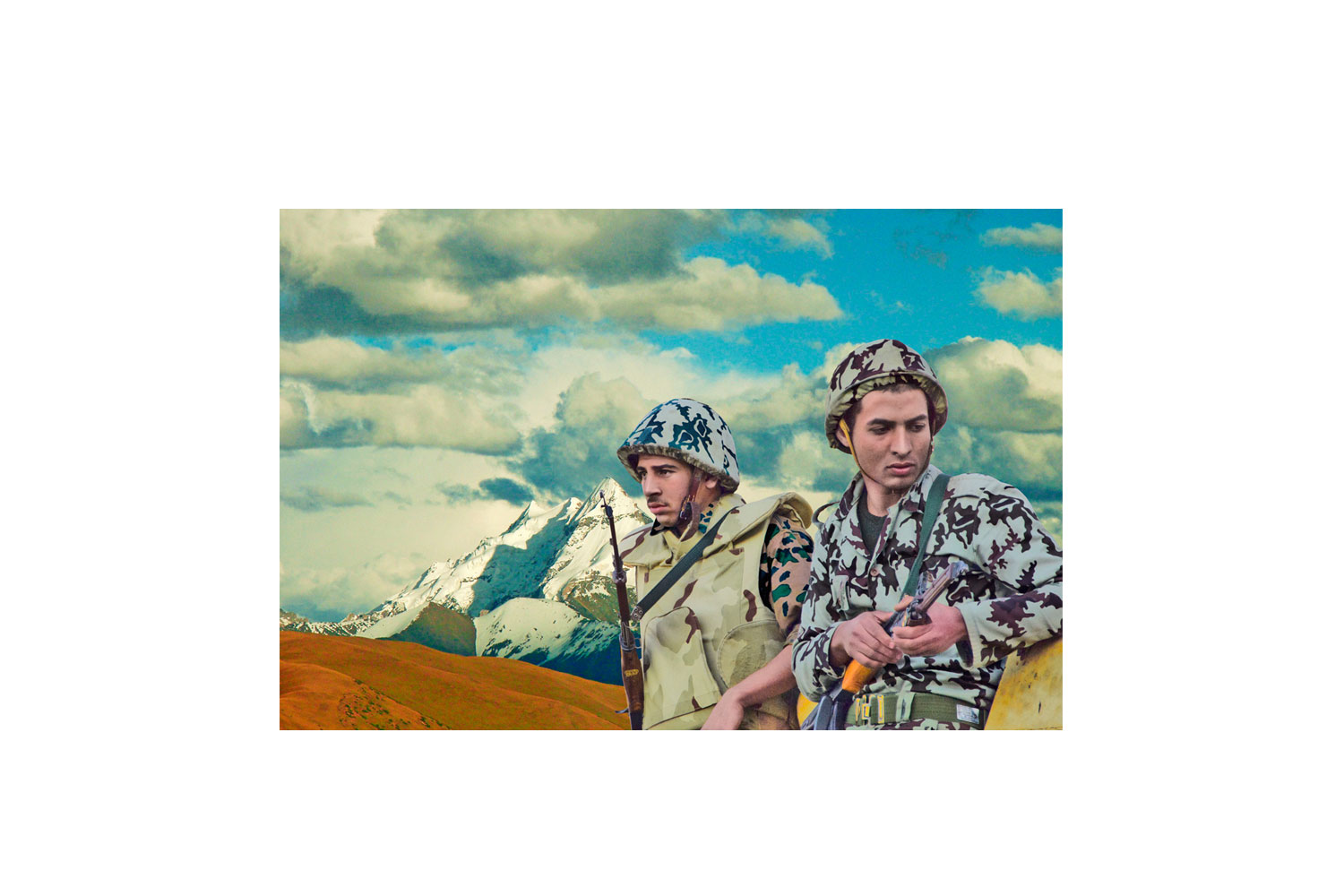

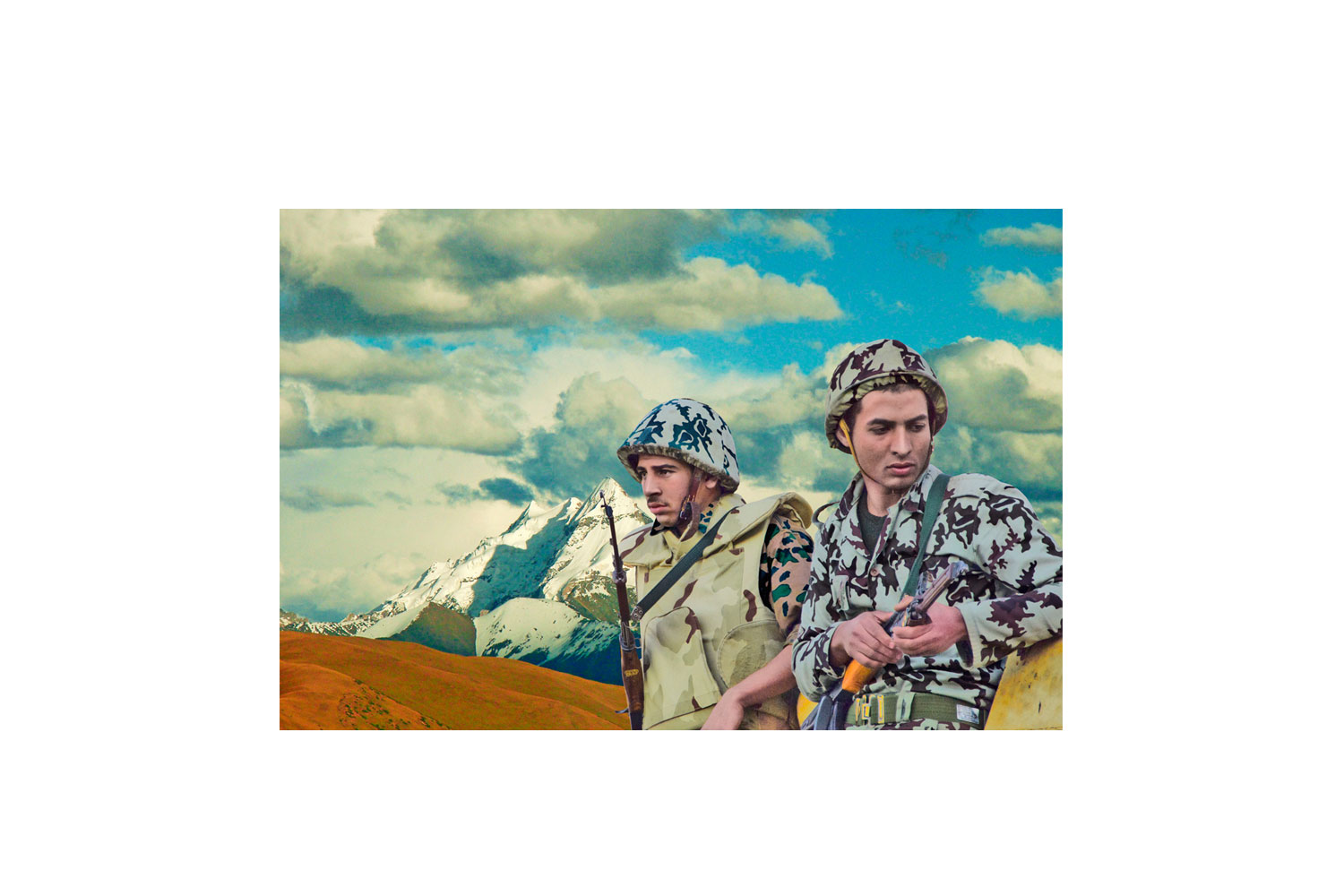

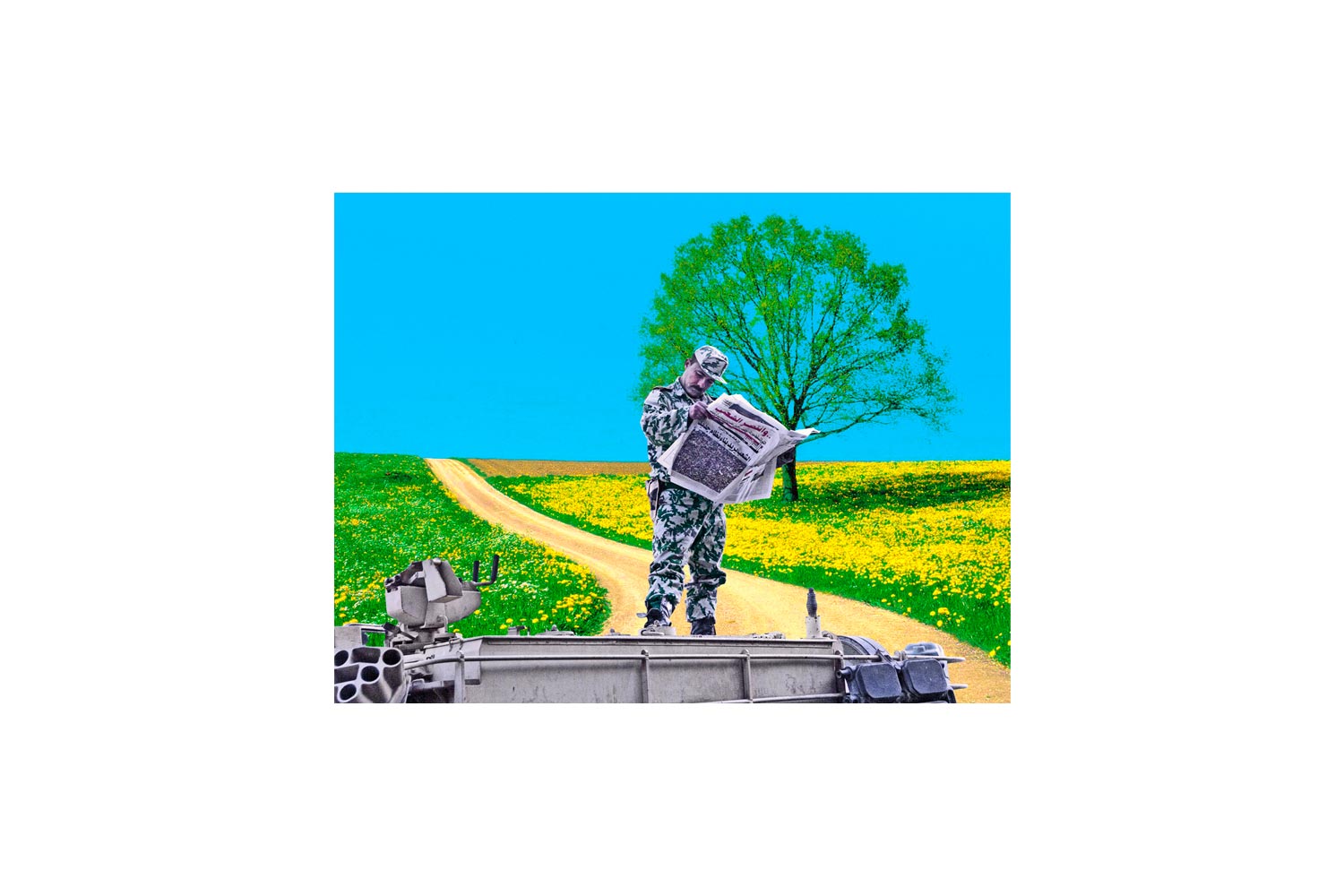

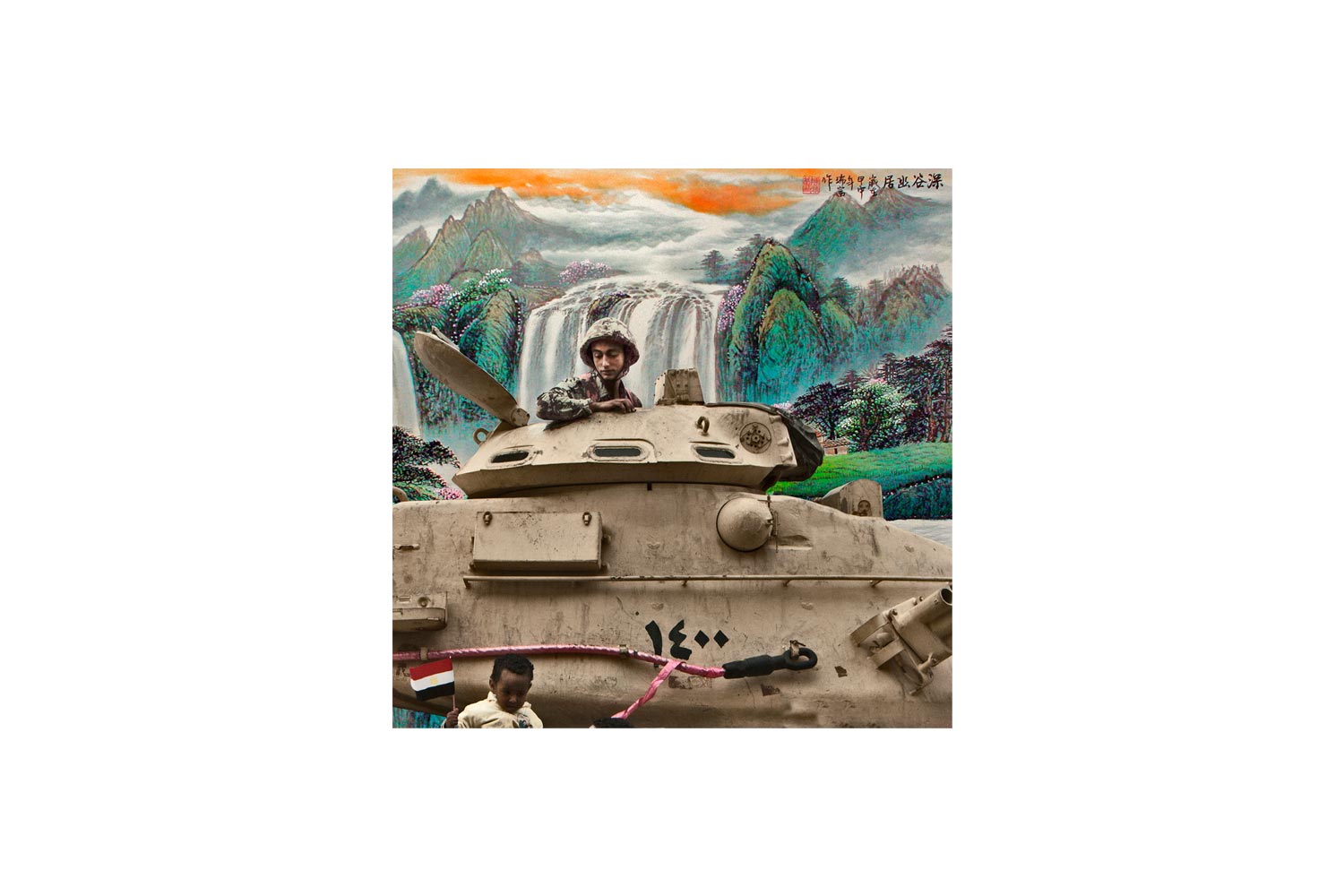

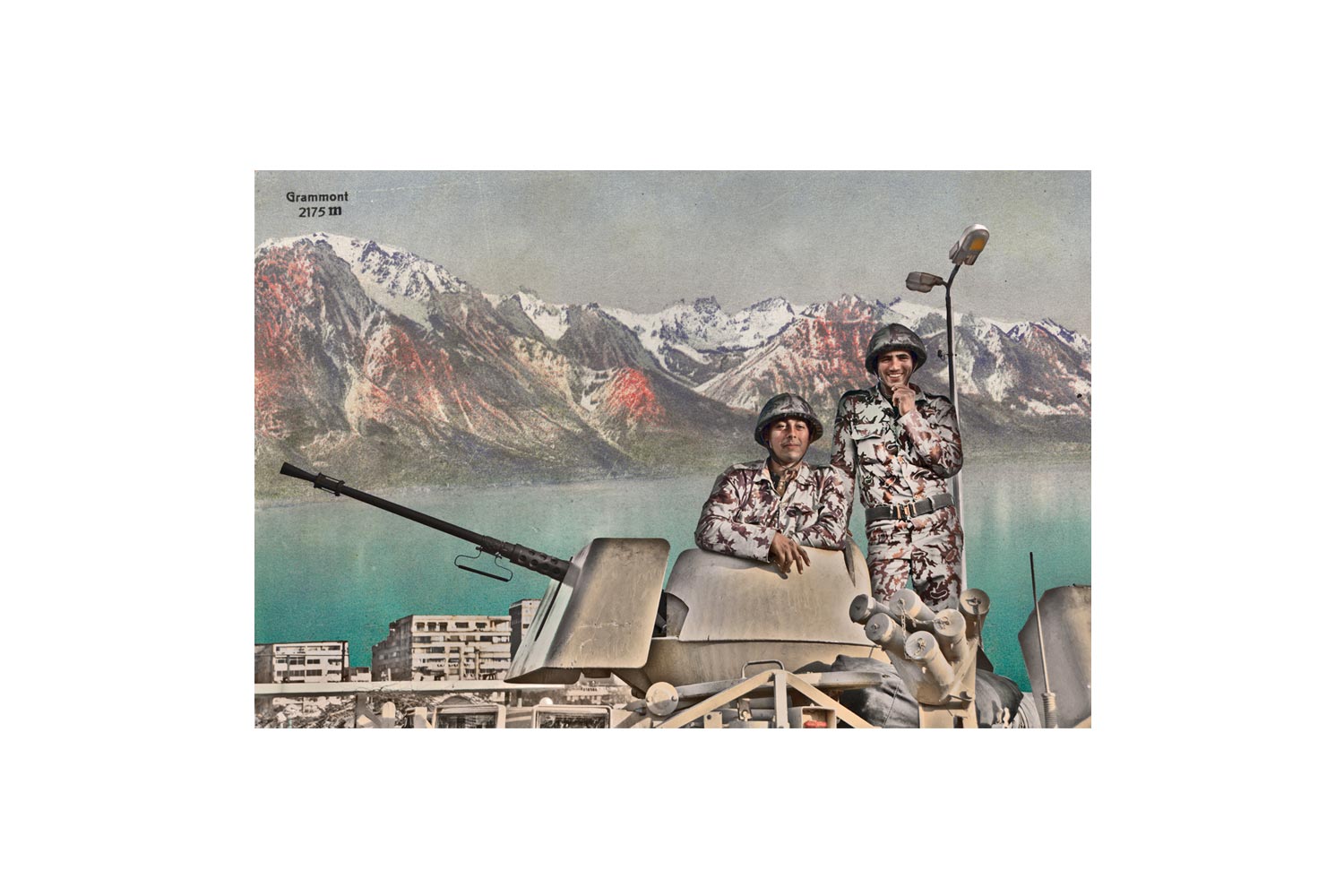

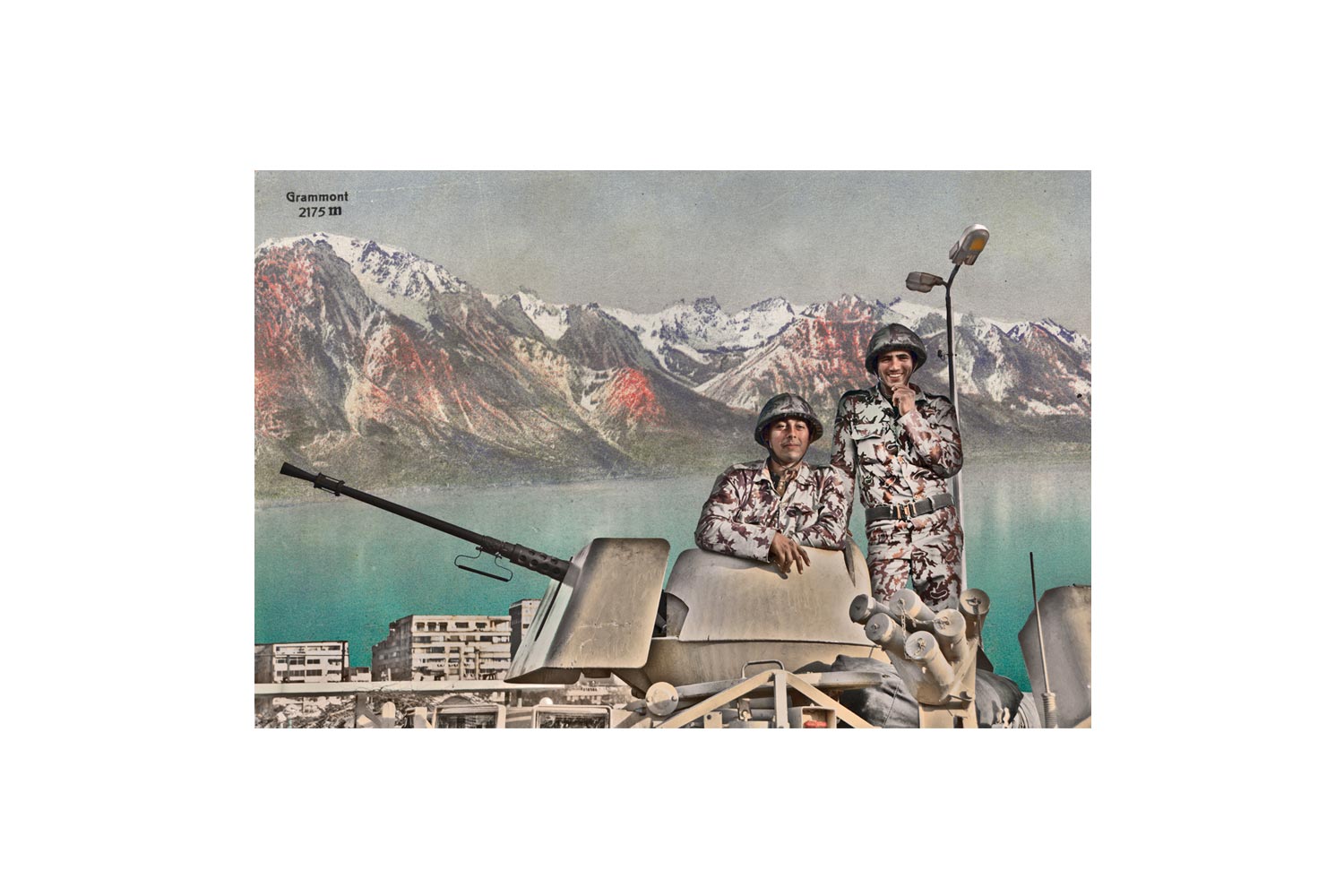

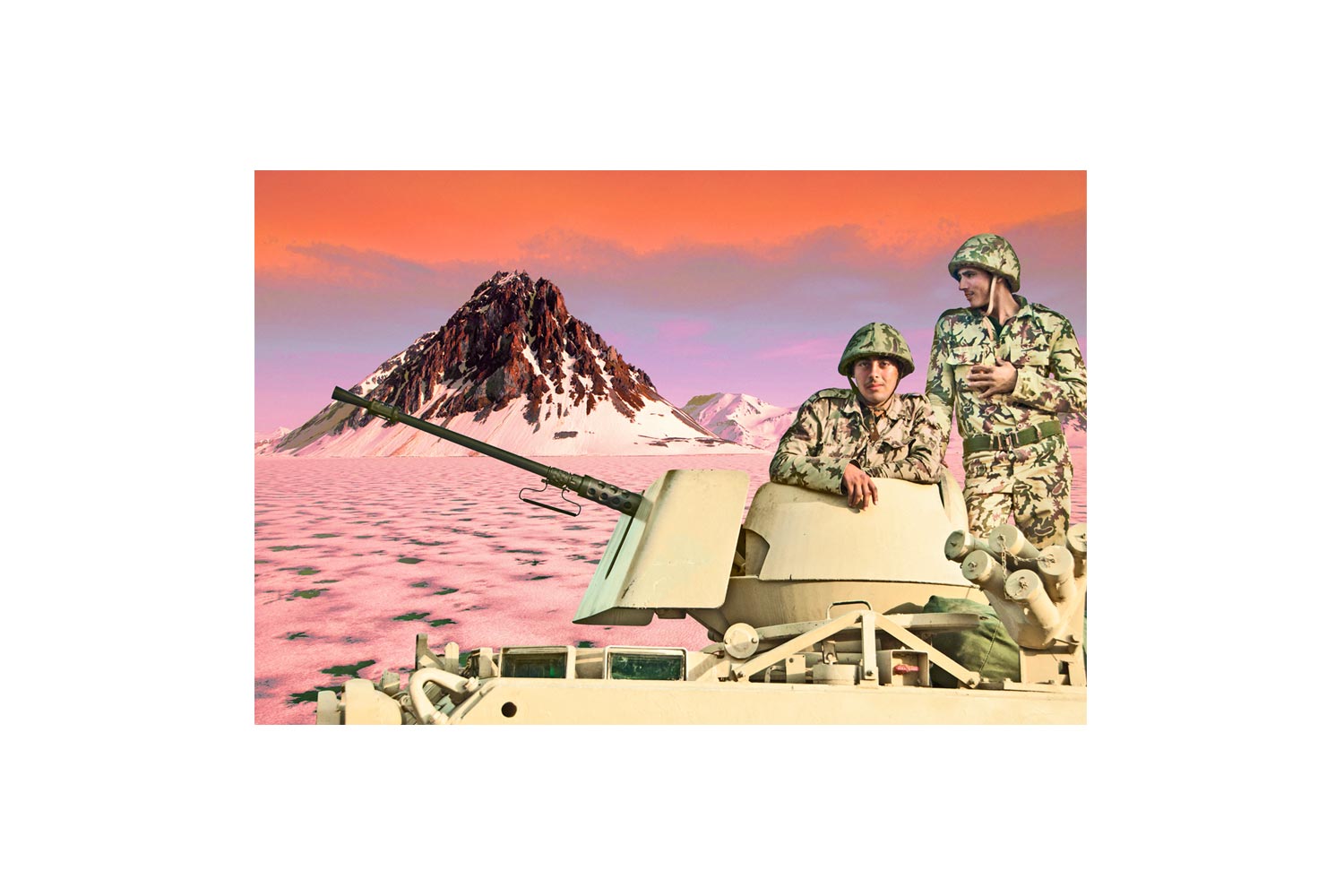

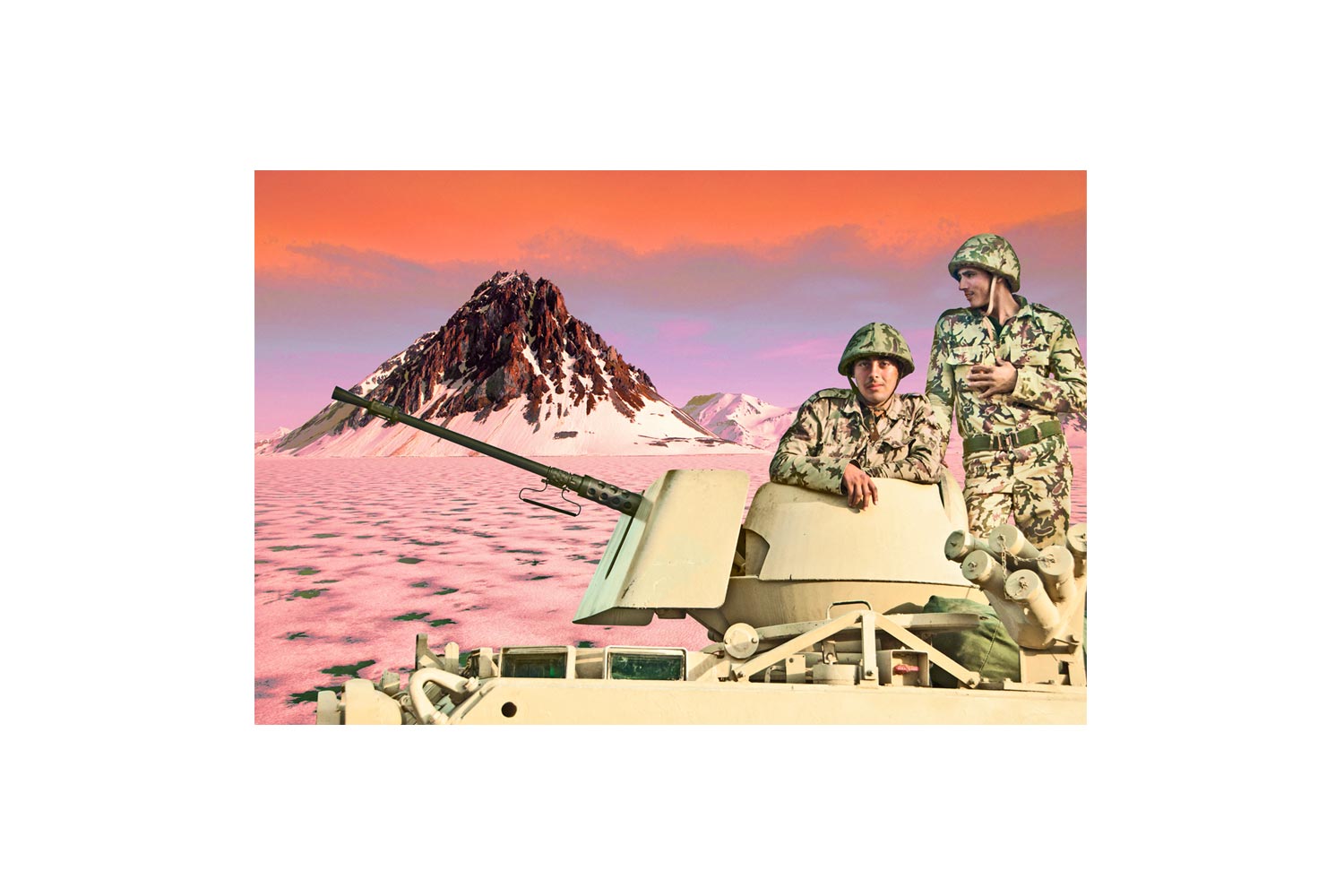

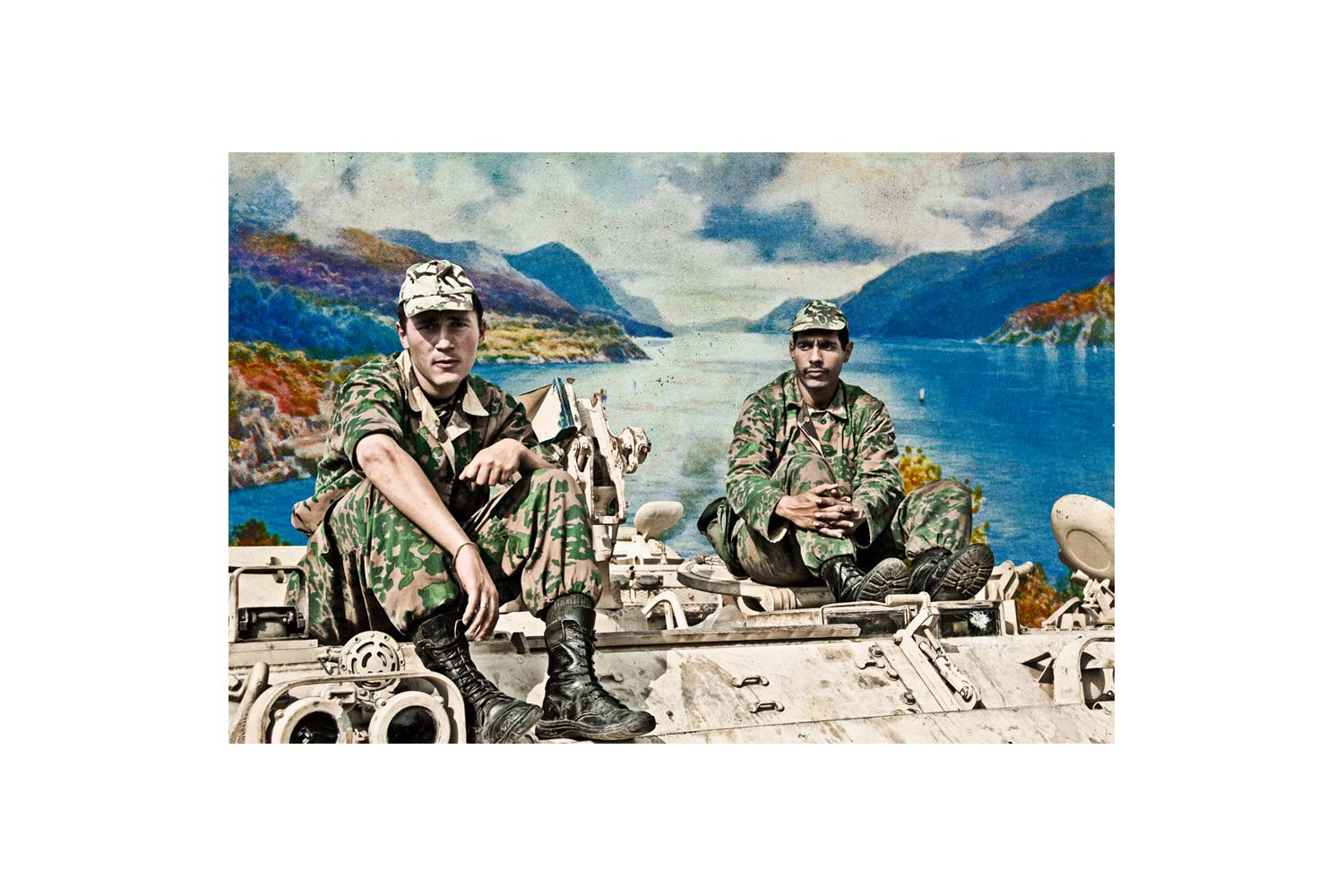

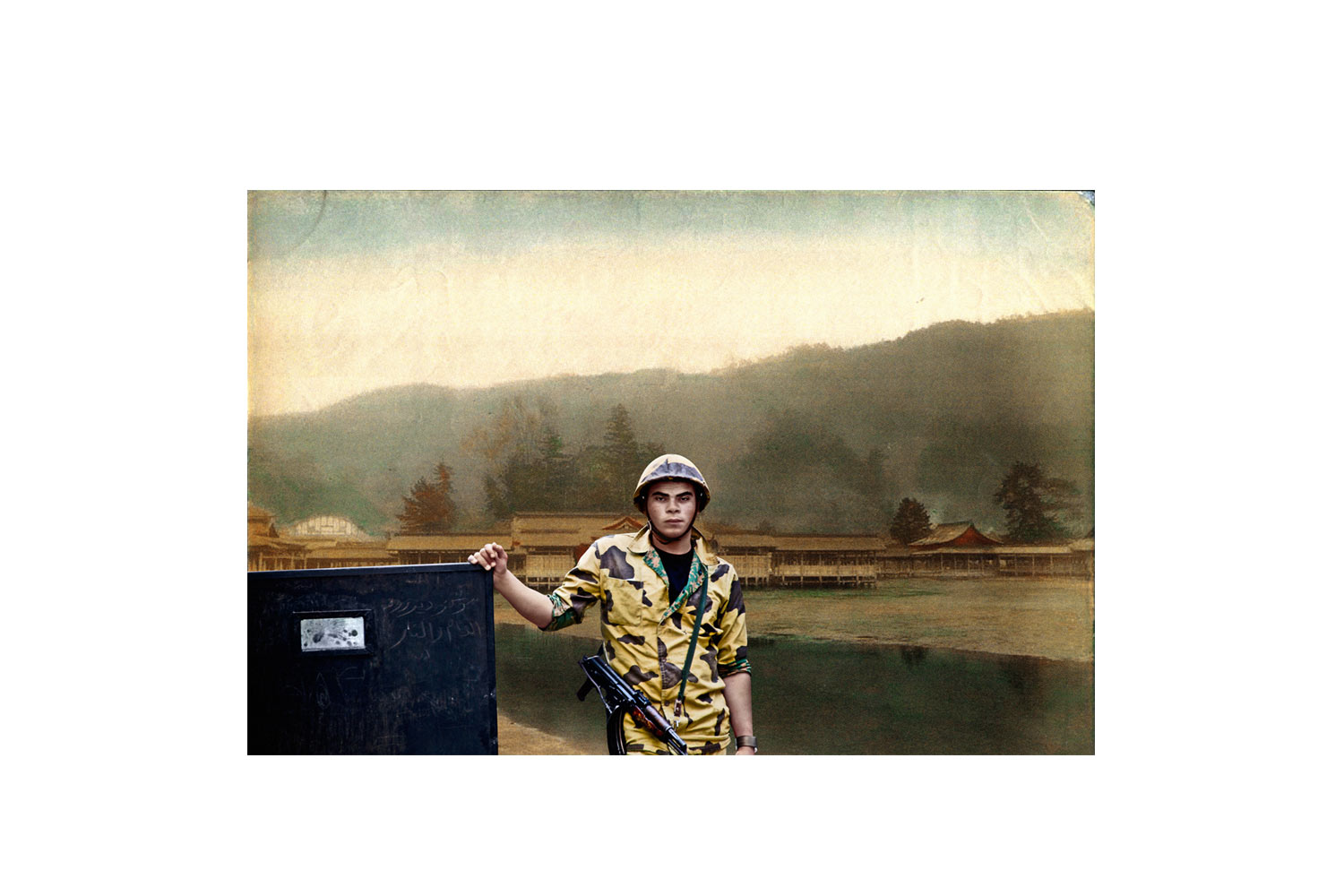

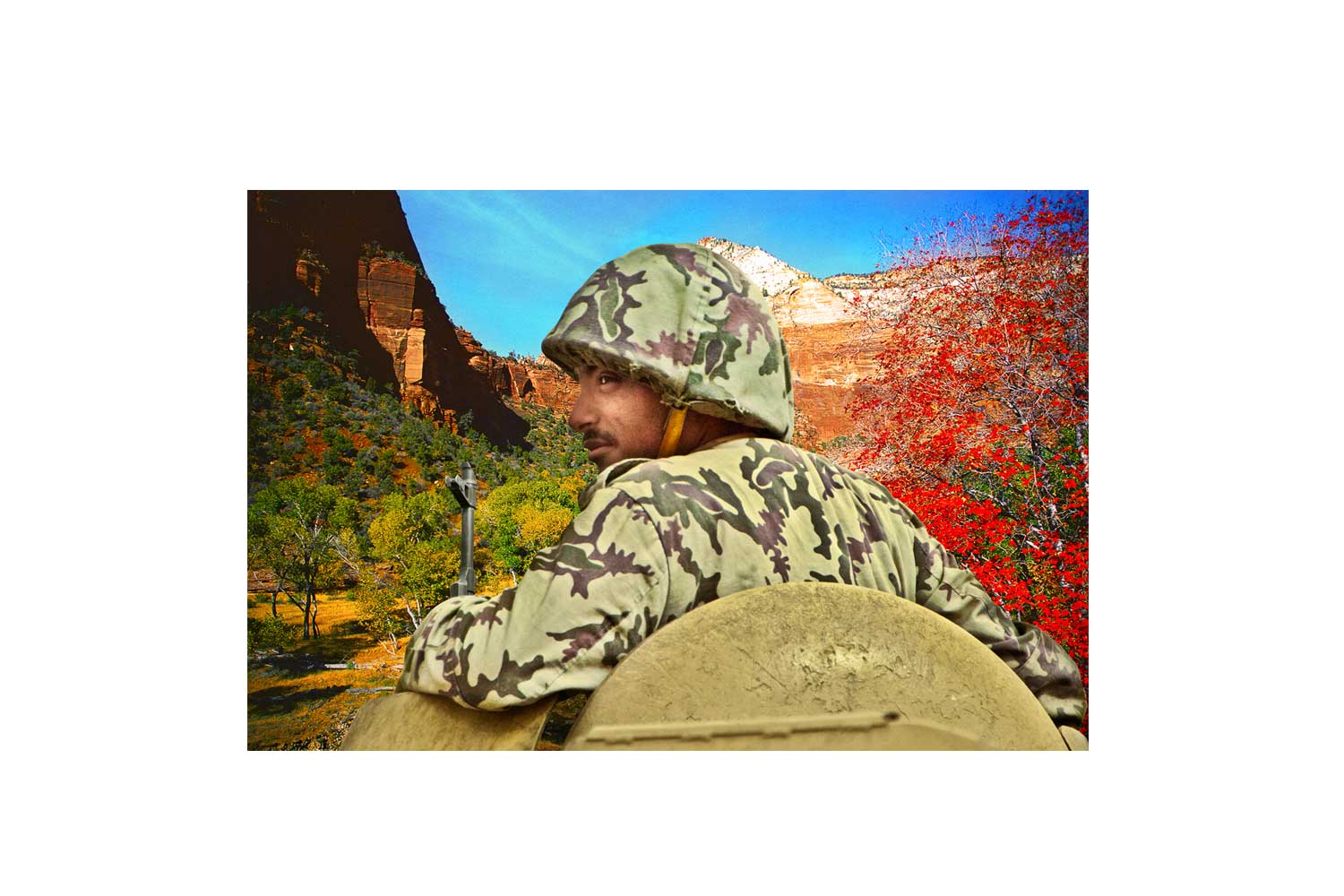

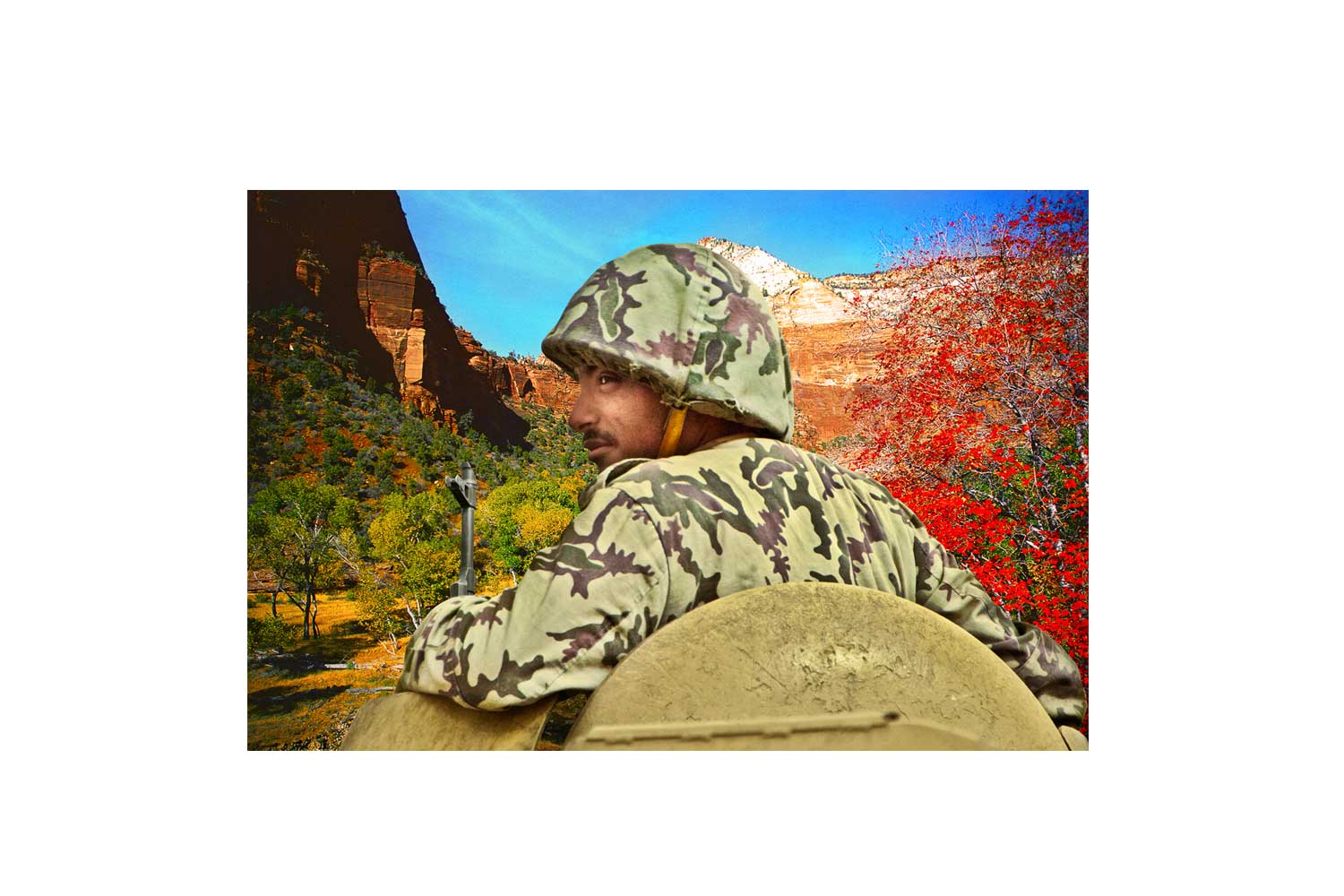

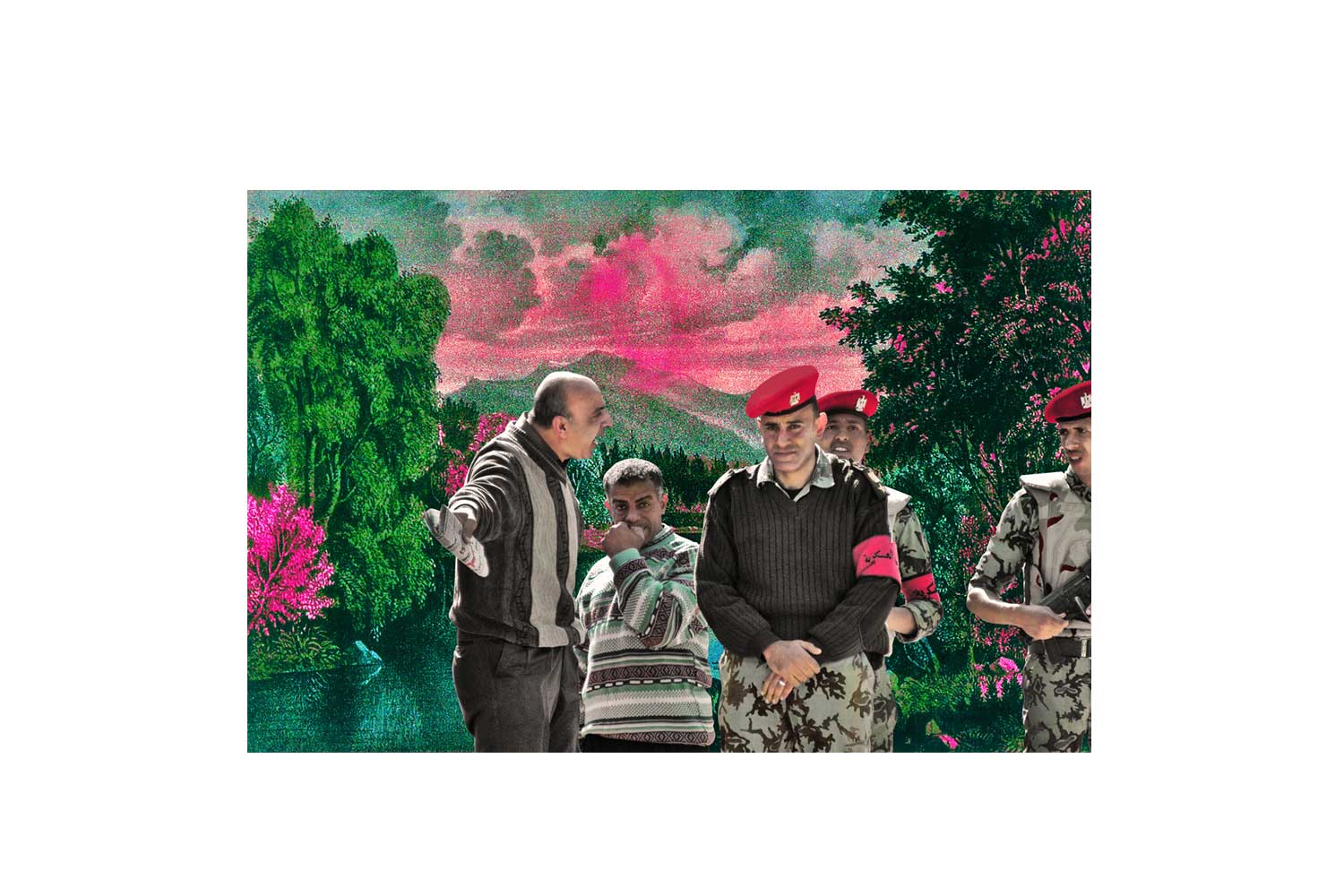

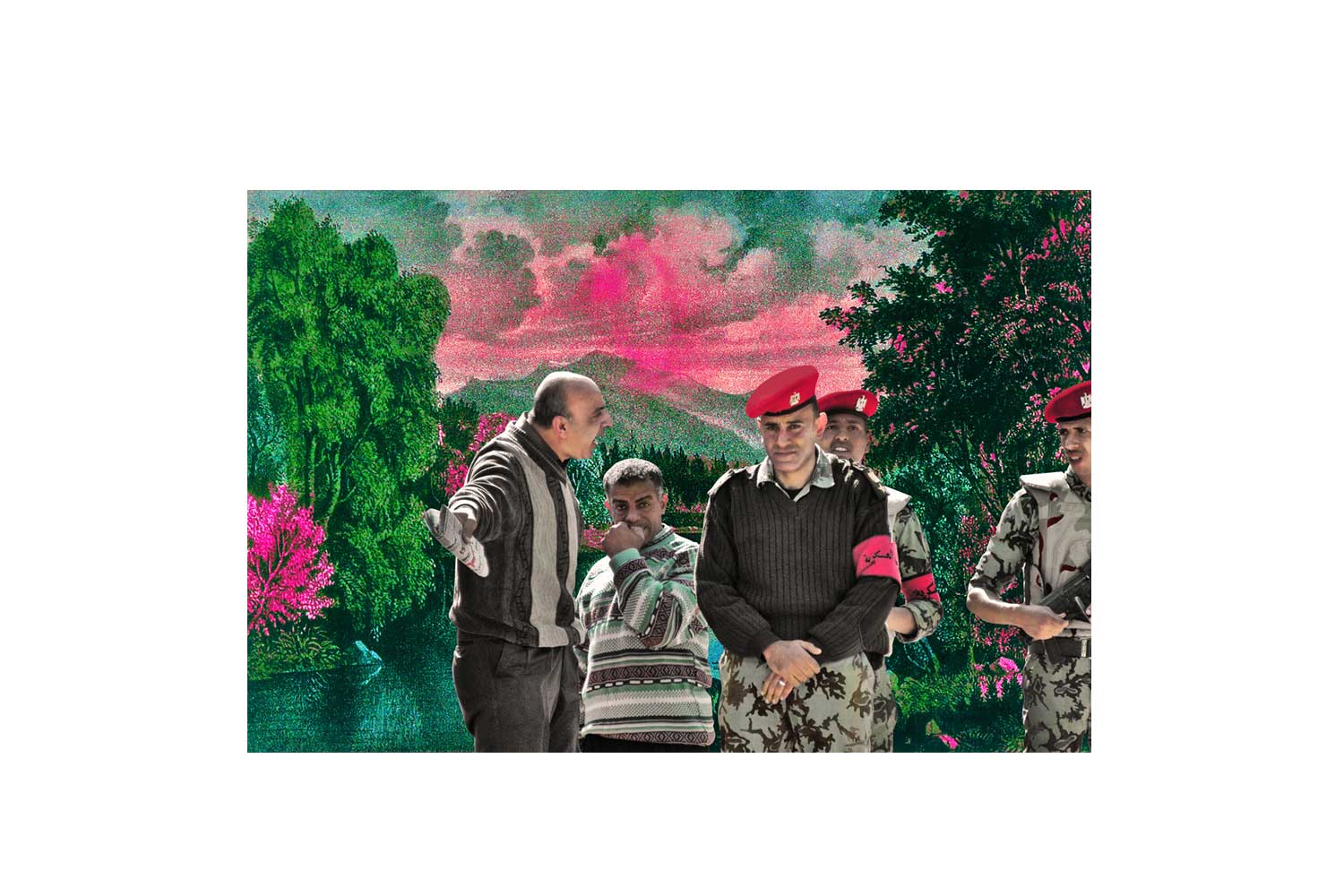

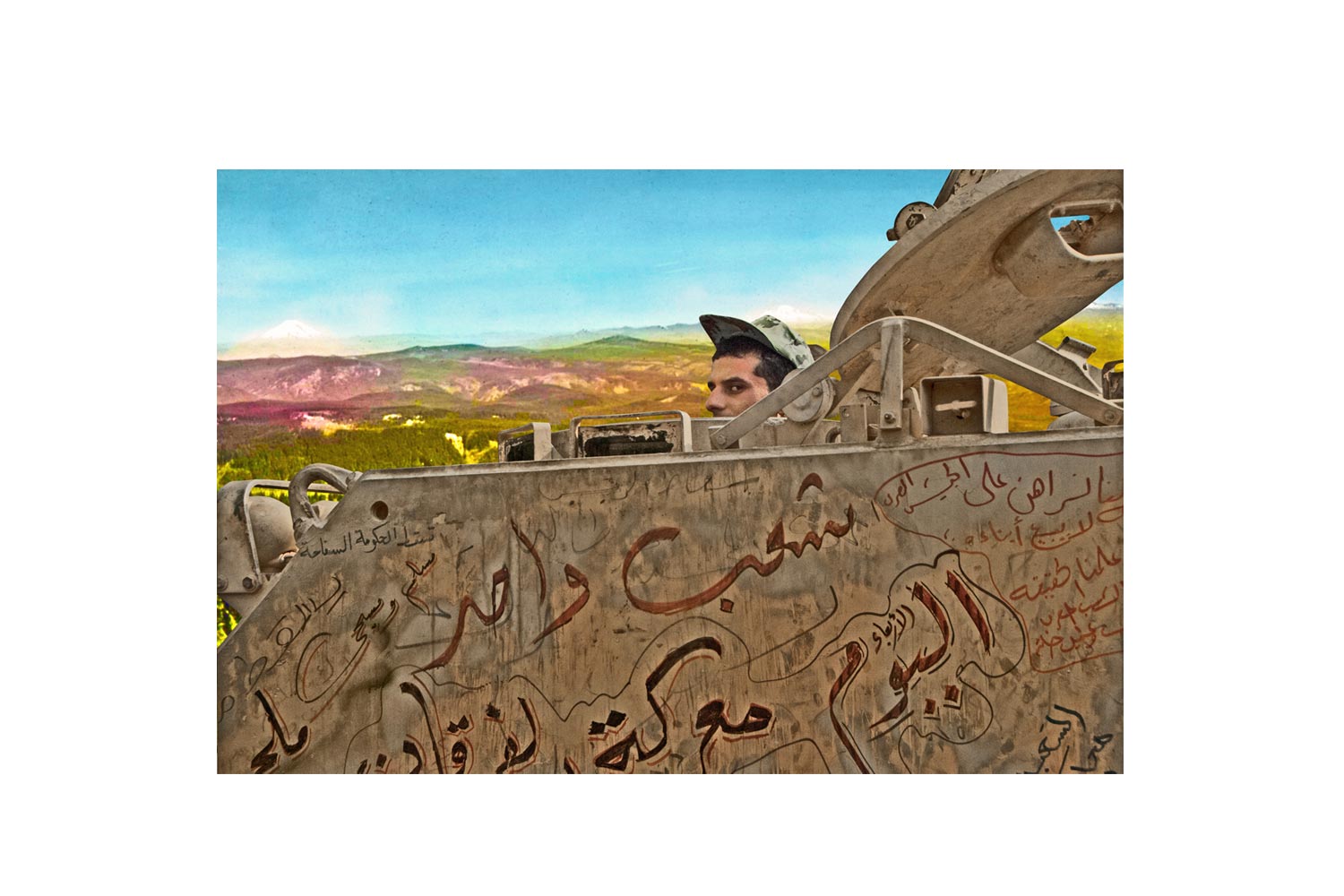

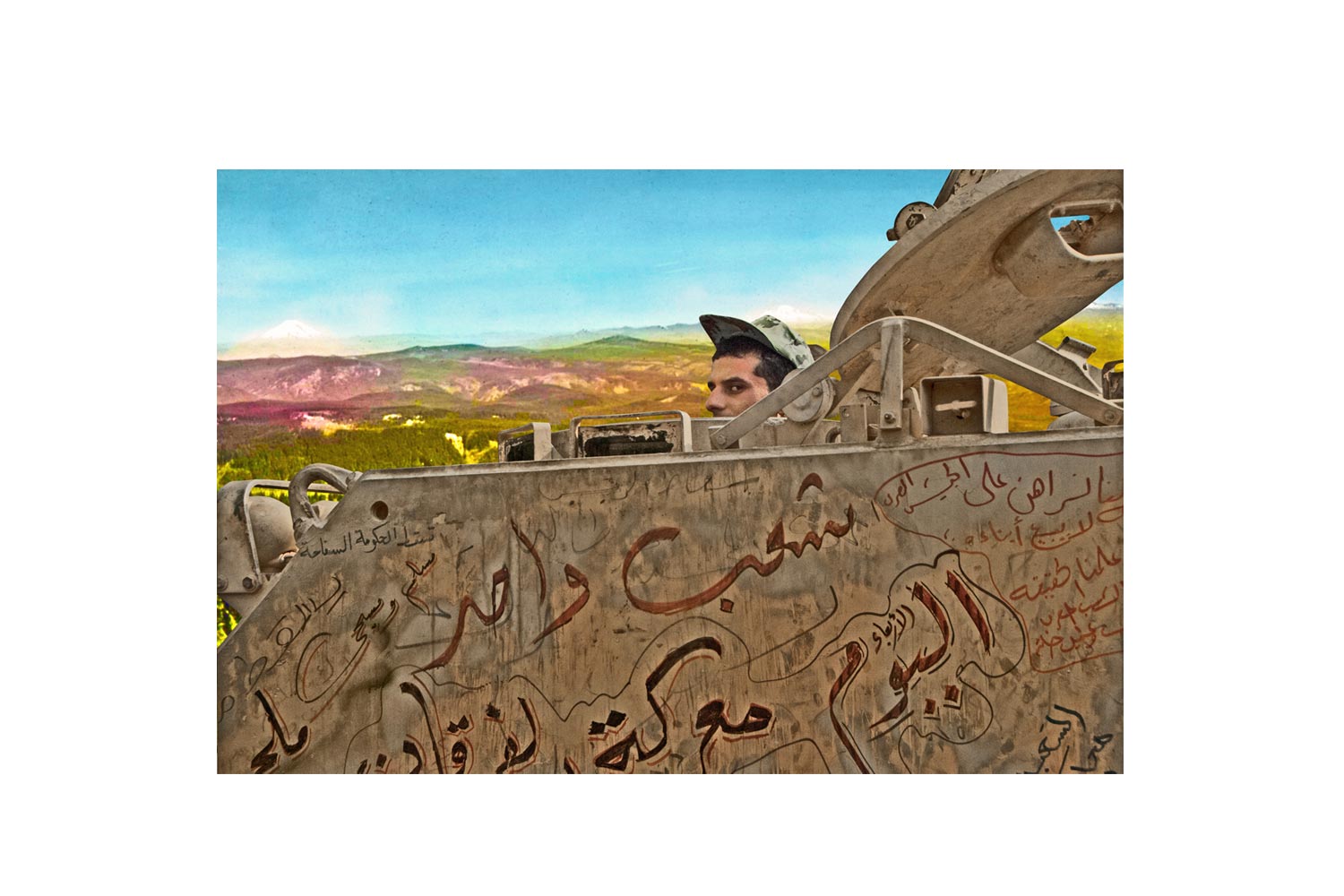

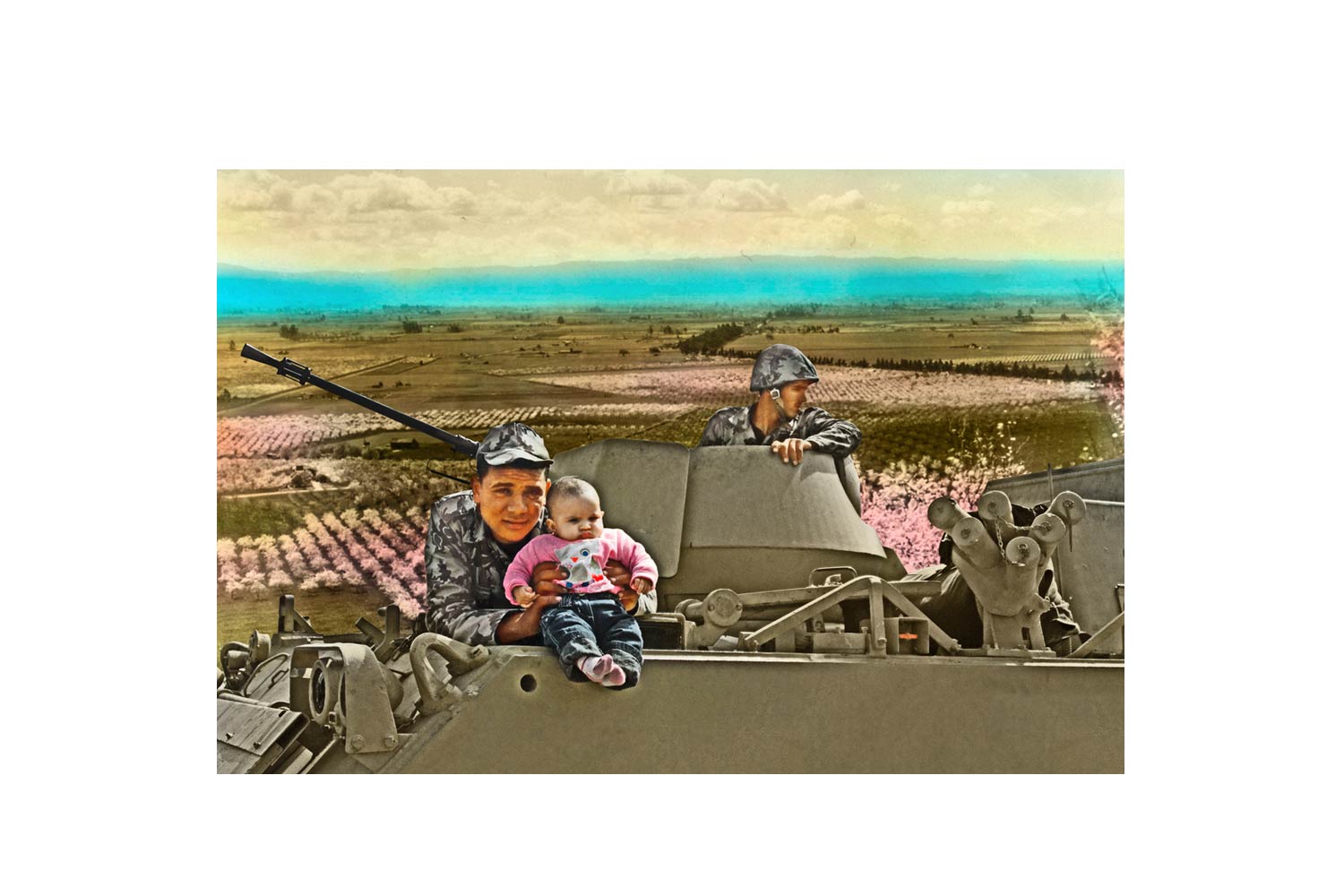

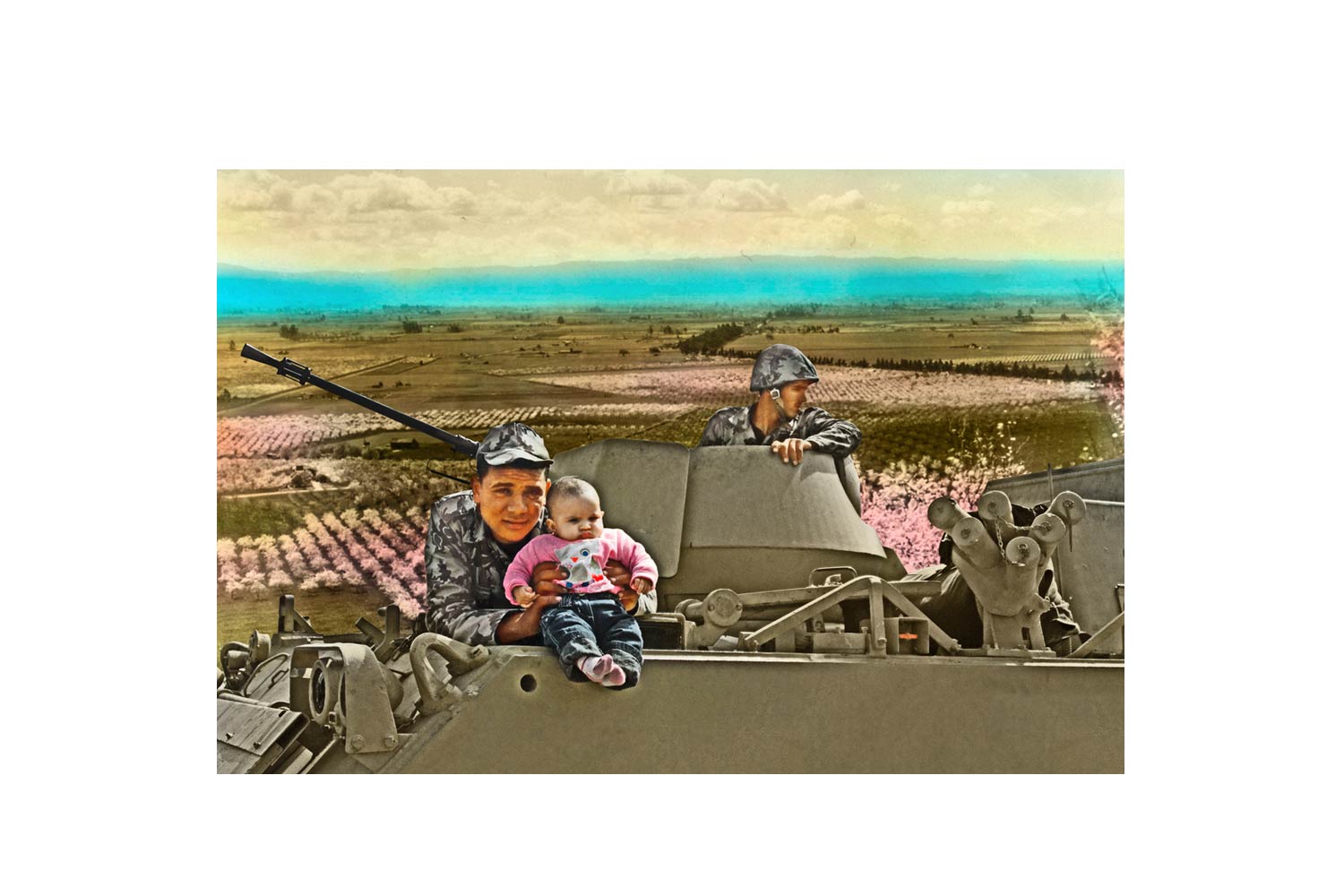

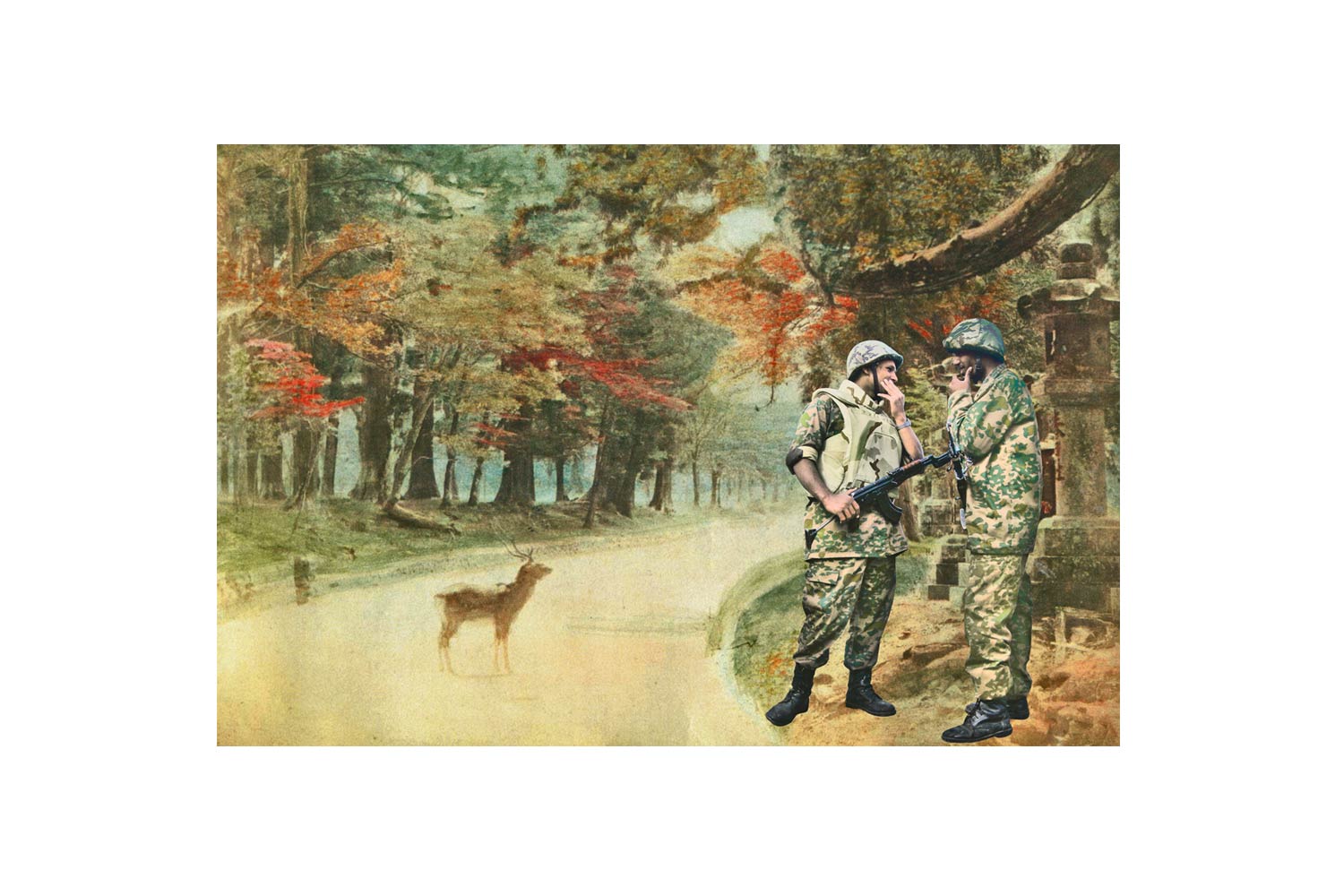

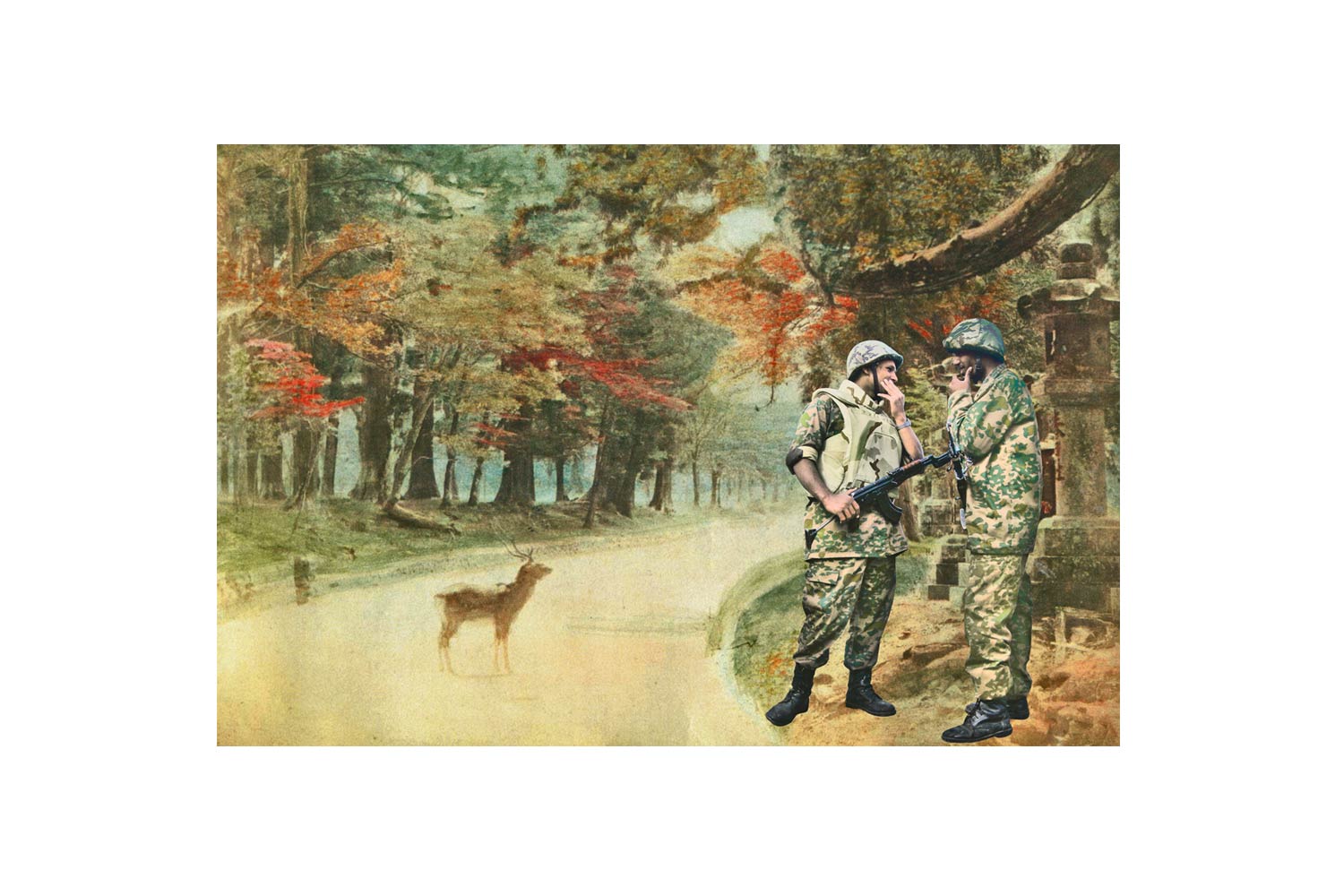

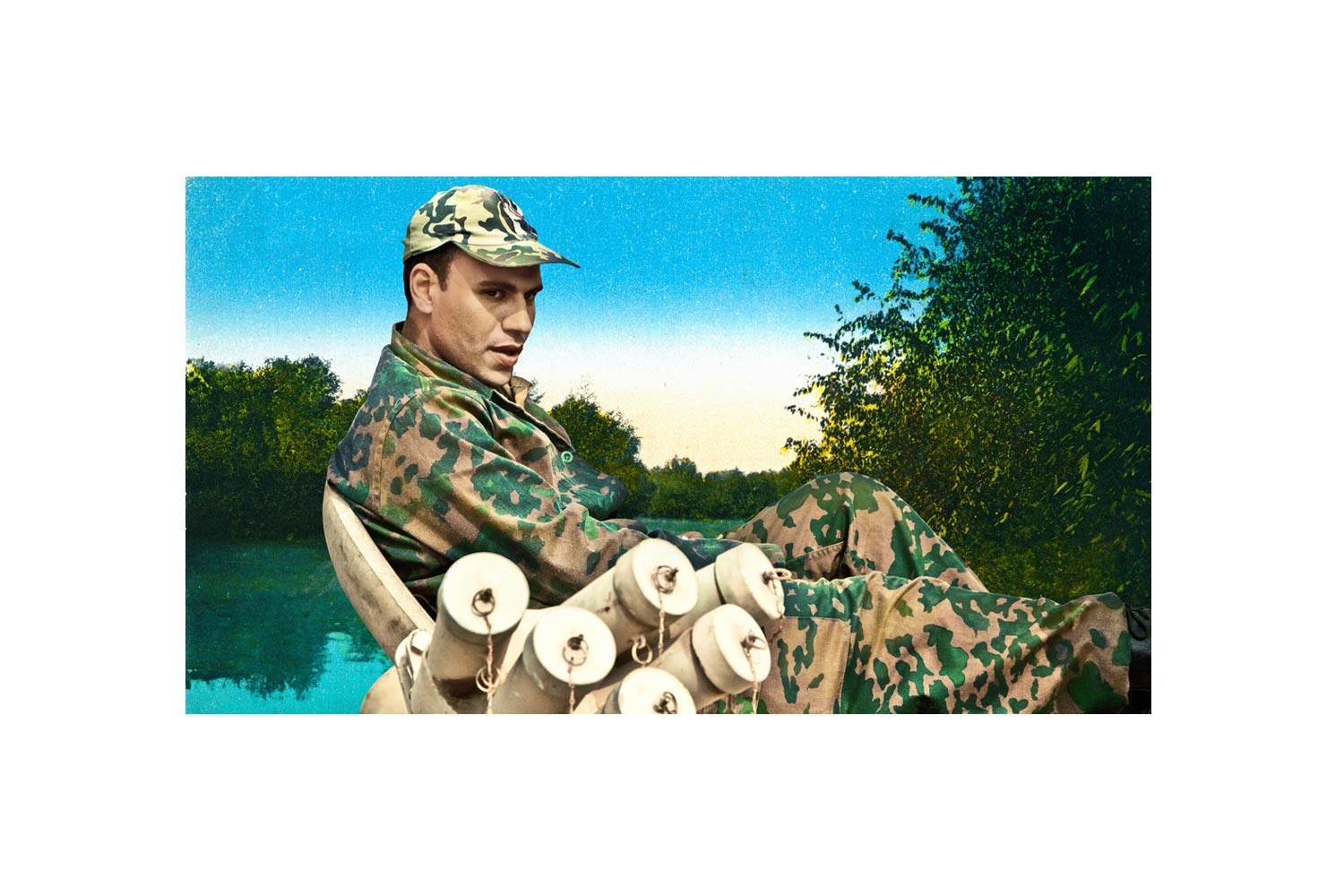

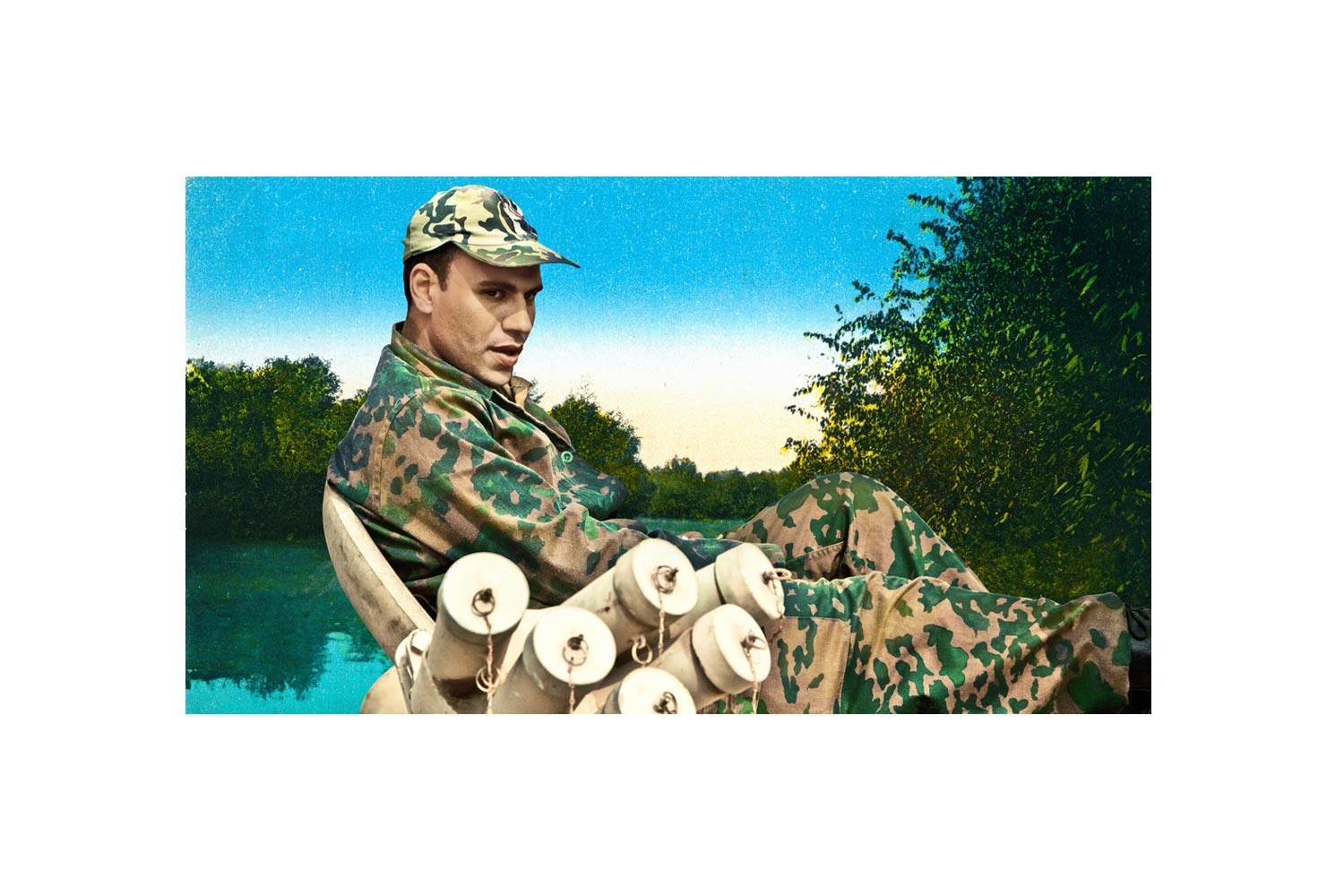

But as the hatches opened, and doors of military vehicles were thrown wide, what emerged was not the angry stereotypes of power and masculinity we expected, but wide-eyed youths with tiny frames, squinting at the cacophony of Cairo. The soldiers’ vulnerability and sheer youth baffled me. I had come to Tahrir to photograph images of military might. Instead, what emerged was its opposite: military tenderness, virile coquetry and masculine frailty.

Watching these young soldiers in ill-fitting army fatigues, astride incongruous military hardware, I wondered: What is power and who, ultimately, wields it? Then it dawned on me: Power is a myth, a construct. It resides only in the images that we hold of it, rather than in its inherent reality.

During that time, the power of the military was symbiotic: a frantic to and fro between army and civilians. Power conferred by onlookers, endorsed by long-held beliefs and projected back on those who looked on it, as fact. Soldiers and citizens, alike, engaged in that transference of power: from us to them and back.

Growing up, we learned that power has a certain ‘look’. Now, I see that it is an elaborate performance complete with props. What transforms wide-eyed youths into the loaded symbol of the army is a carefully choreographed performance of uniforms and equipment, a strength in numbers, a united display of force.

In the act of photographing the soldiers, unwittingly the individual was reclaimed from the group, “re-personalizing” the “de-personalized” and unmasking the spectacle. Individual soldiers were caught in unguarded moments, laying down their display of power, young and vulnerable amidst their gadgetry. In this process, I found myself approaching power from an unexpected vantage point; allowing me to see that other side of power: the frailty that crouches behind stereotypes of force masquerading in a regalia of military hardware.

After seeing these protagonists, so young, innocent and de-masculinized, I felt an urge to parody propaganda posters from the 1940s and 1950s that feature strong nubile men and women in idealized settings; posters parading power to the masses. During the 18 days of revolution, in the face of thousands of peaceful protestors, the army seemed inactive, observers of the scene before them. Military power appeared to me deflected and disarmed, turned in on itself, by the indomitable power of peaceful confrontation. Perhaps power cannot survive without powerlessness: it is robbed of its hegemony. The backgrounds emphasize the discordant presence of armed men among civilians in Tahrir: men of war in Paradise.

I have often wondered if photography offers the power to see behind the mask. Does it seek to destabilize, picking up that which should be seen and that which must remain hidden? Was the very act of photographing soldiers a personal gesture of subversion– an inversion of traditional hierarchies of power? As a woman, I zoomed into this masculine sphere from which I am traditionally excluded. To photograph the soldiers was to present the possibility of them as young and vulnerable , desiring and desired.

Our collective subconscious favours large, overarching symbols of power, to the smaller, real life narratives that make up human experience. We prefer the two-dimensional, mass-produced images of Stalin, or Mao, or the faceless facade of military might, to life’s myriad microcosms of power. The postcards act as a balance to this. Unlike the staged invincibility of the military machine, postcards admit to the delicacy of memory. Peace and tranquility can only ever be experienced as transient and fleeting. Postcards are an attempt to send these specific emotions into the future. All that is left of power is the image of it; it stays in our psyche as picture.

The Utopian form of the postcards betrays a peculiar nostalgia. The work anticipates its own fading, the reframing of revolutionary dreams as mundane political history. After all, “Upekkha” captures a particular moment in time that can never be relived. The nostalgic memory of an organization, so sparing in its appearances and generous in its dealings with the people, is now hard to recall.

Upehkka refers to the Buddhist aspiration of experiencing the world through a lens of equanimity. Perfecting detachment offers the opportunity to reorganize society differently, to notice the contradictions within the images. Social upheaval requires us to consider the coquettish smile of a soldier in khaki, the precariousness of a paradisiacal landscape. We must work out how to fear and admire, fight off and channel, mock and respect the terrible frailty of power.

90 x 50 cm

90 x 50 cm

90 x 50 cm

90 x 50 cm

90 x 60 cm

90 x 60 cm

60 x 96

50 x 50 cm

90 x 50 cm

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit

Nulla blandit