Unfolding

Rice Paper 100 grm - Alpha Cellulose White

“To suffer is one thing; another thing is living with the photographed images of suffering, which does not necessarily strengthen conscience and the ability to be compassionate...Once one has seen such images, one has started down the road of seeing more and more….after repeated exposure to images (an event) becomes less real” Susan Sontag, On Photography.

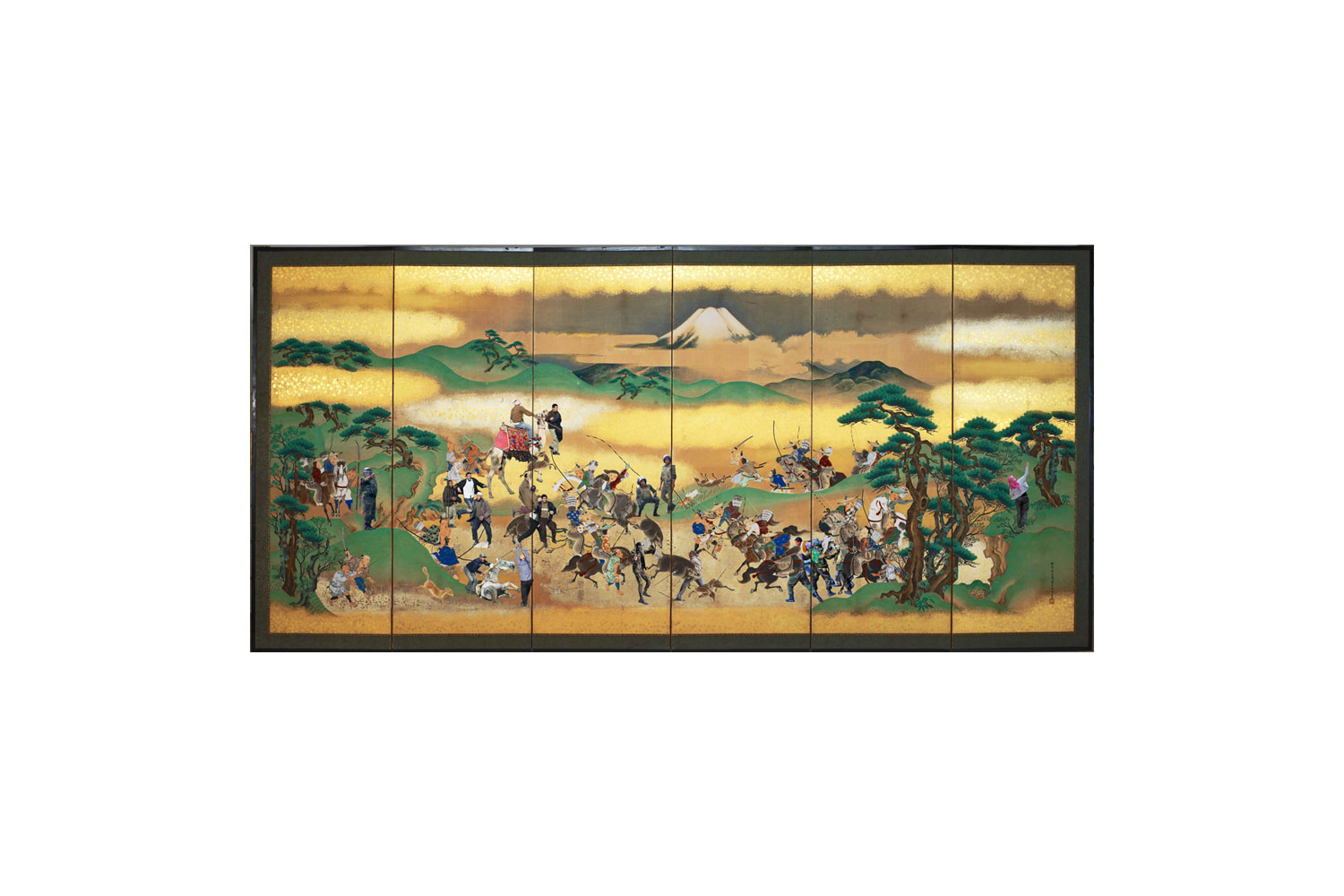

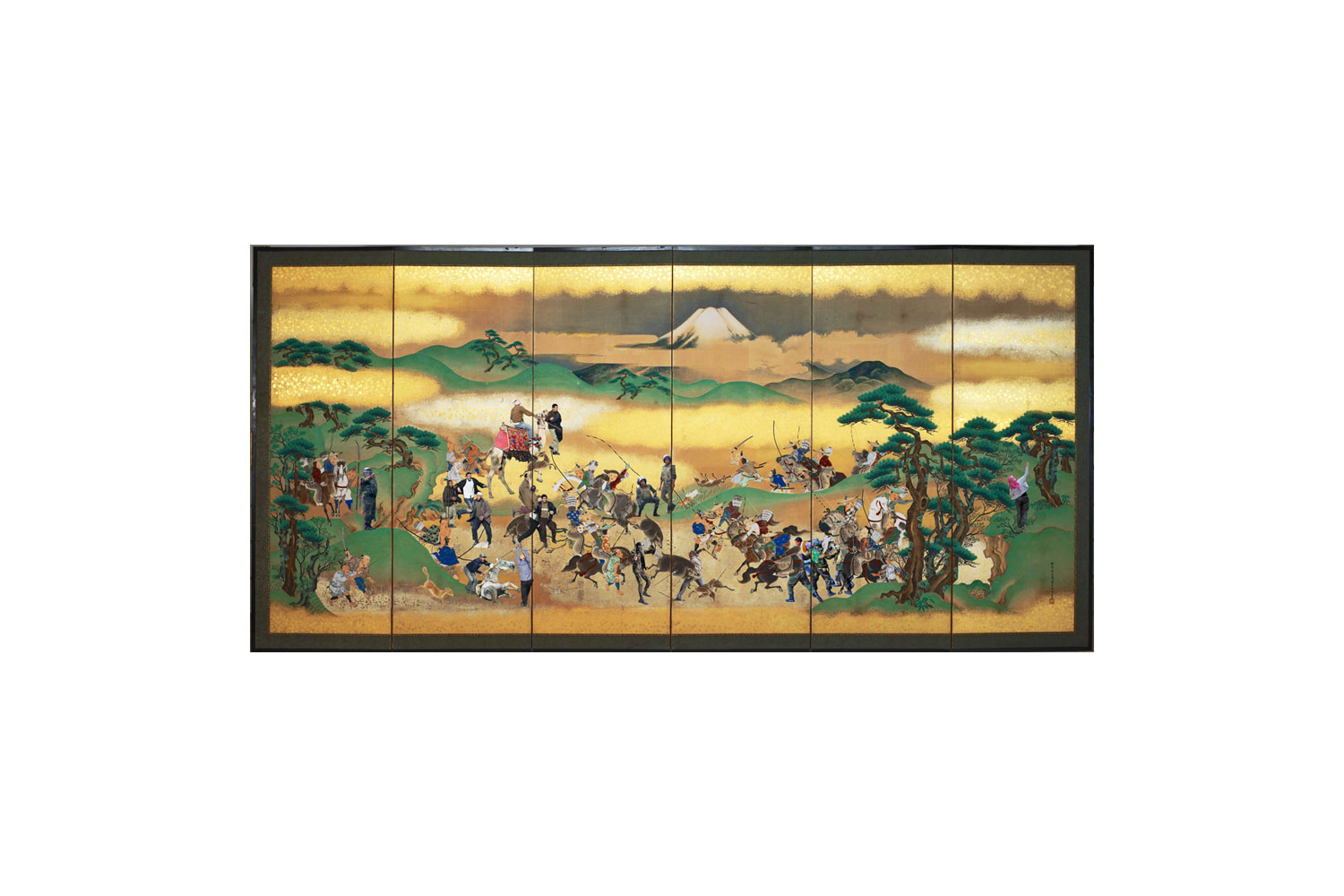

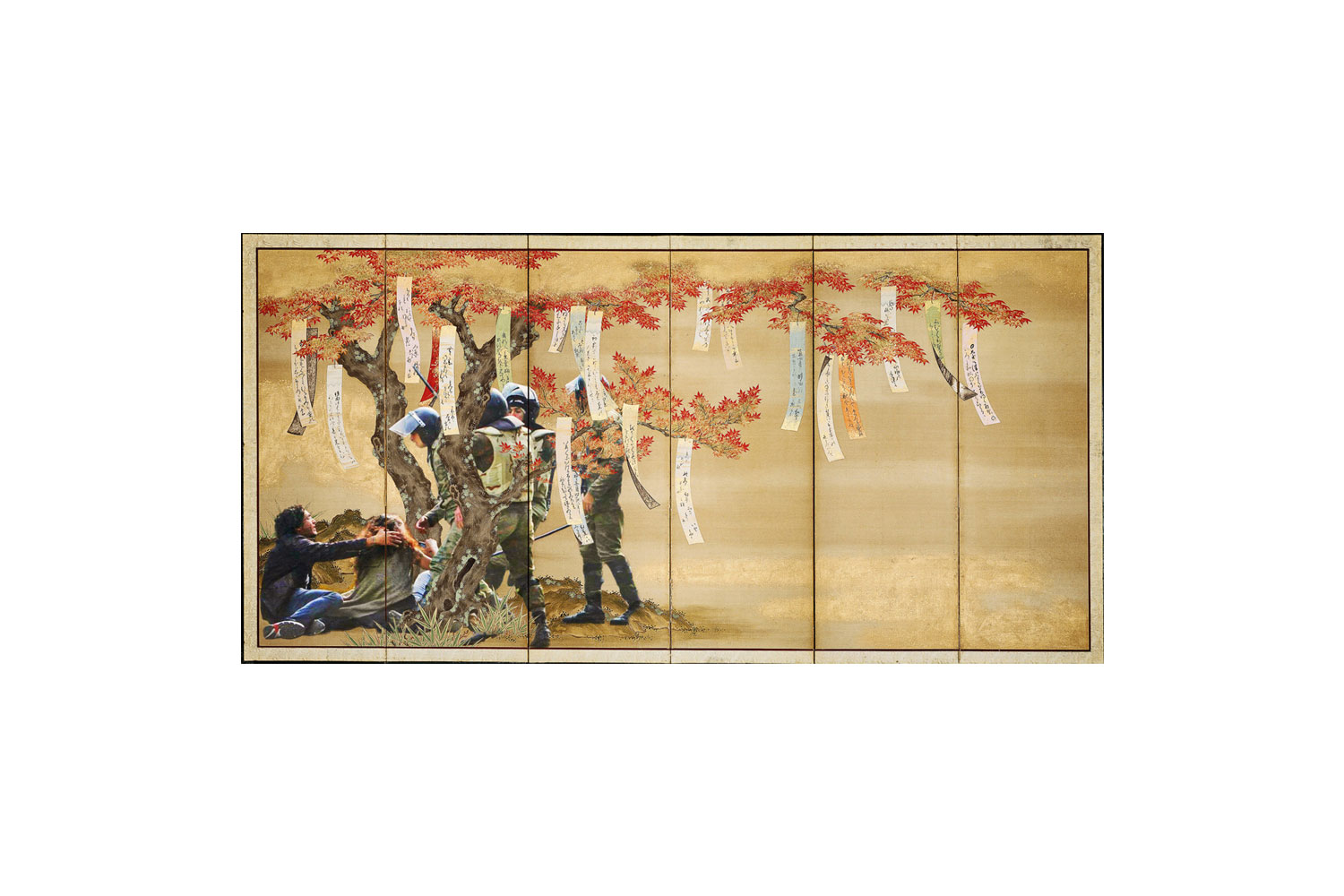

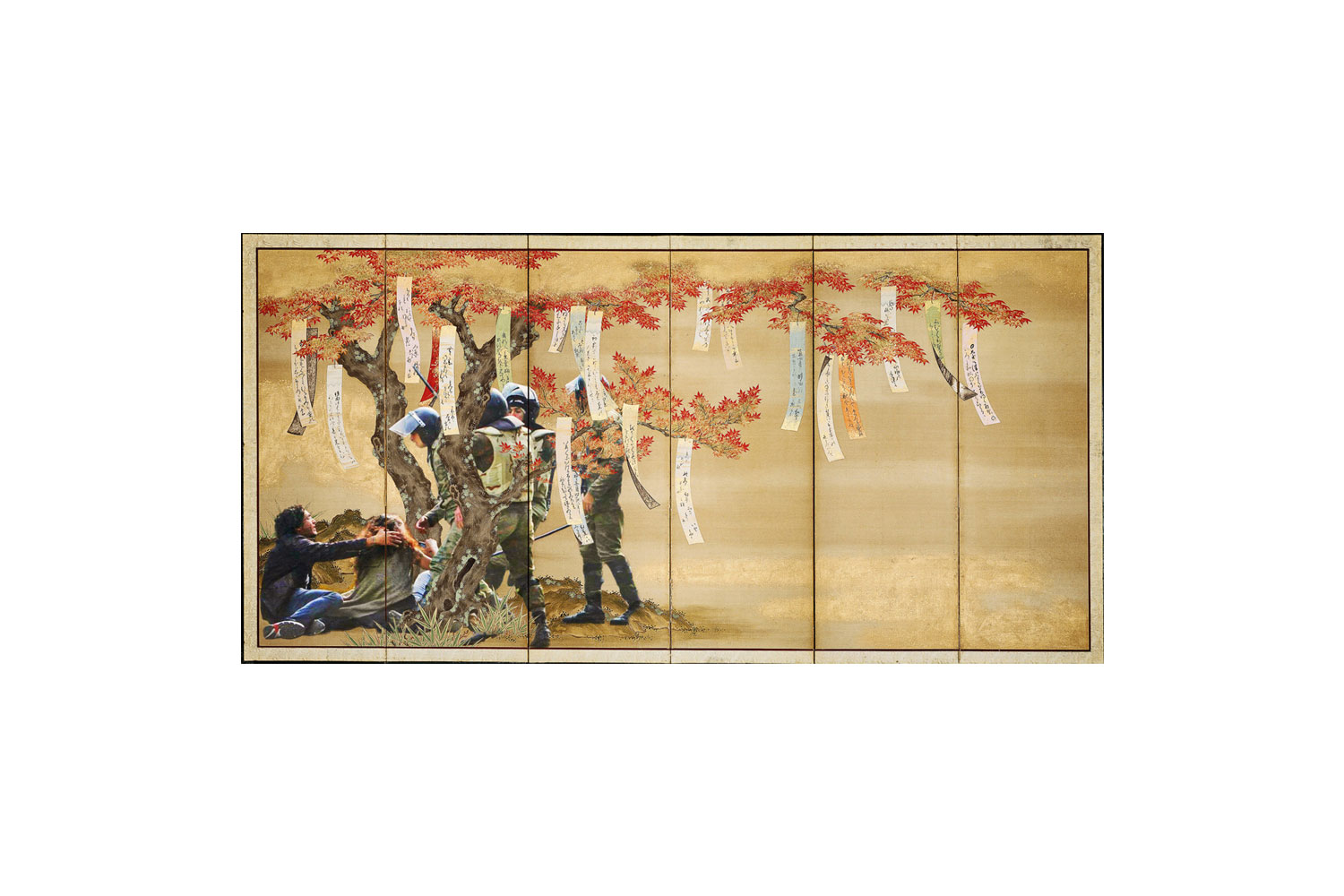

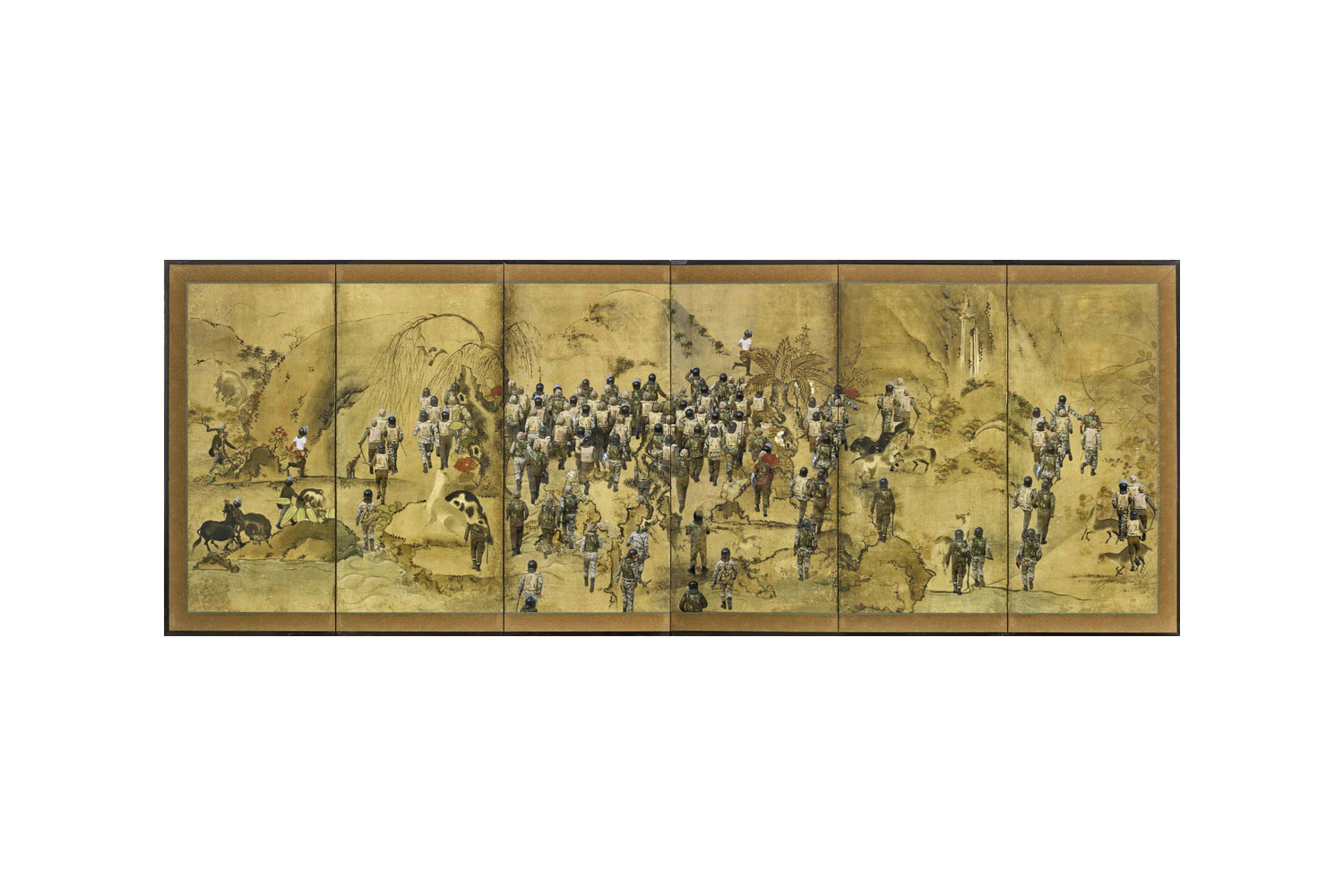

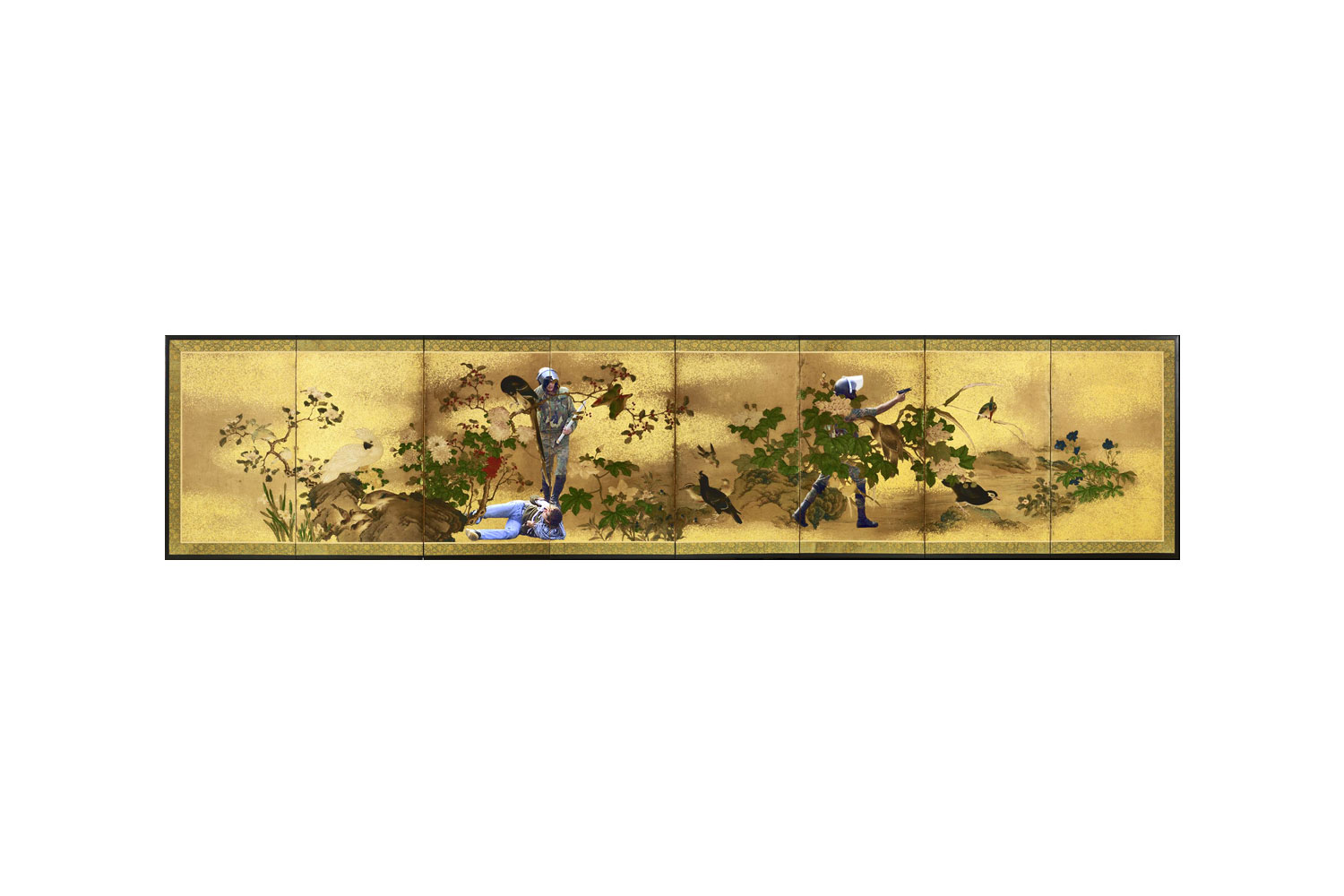

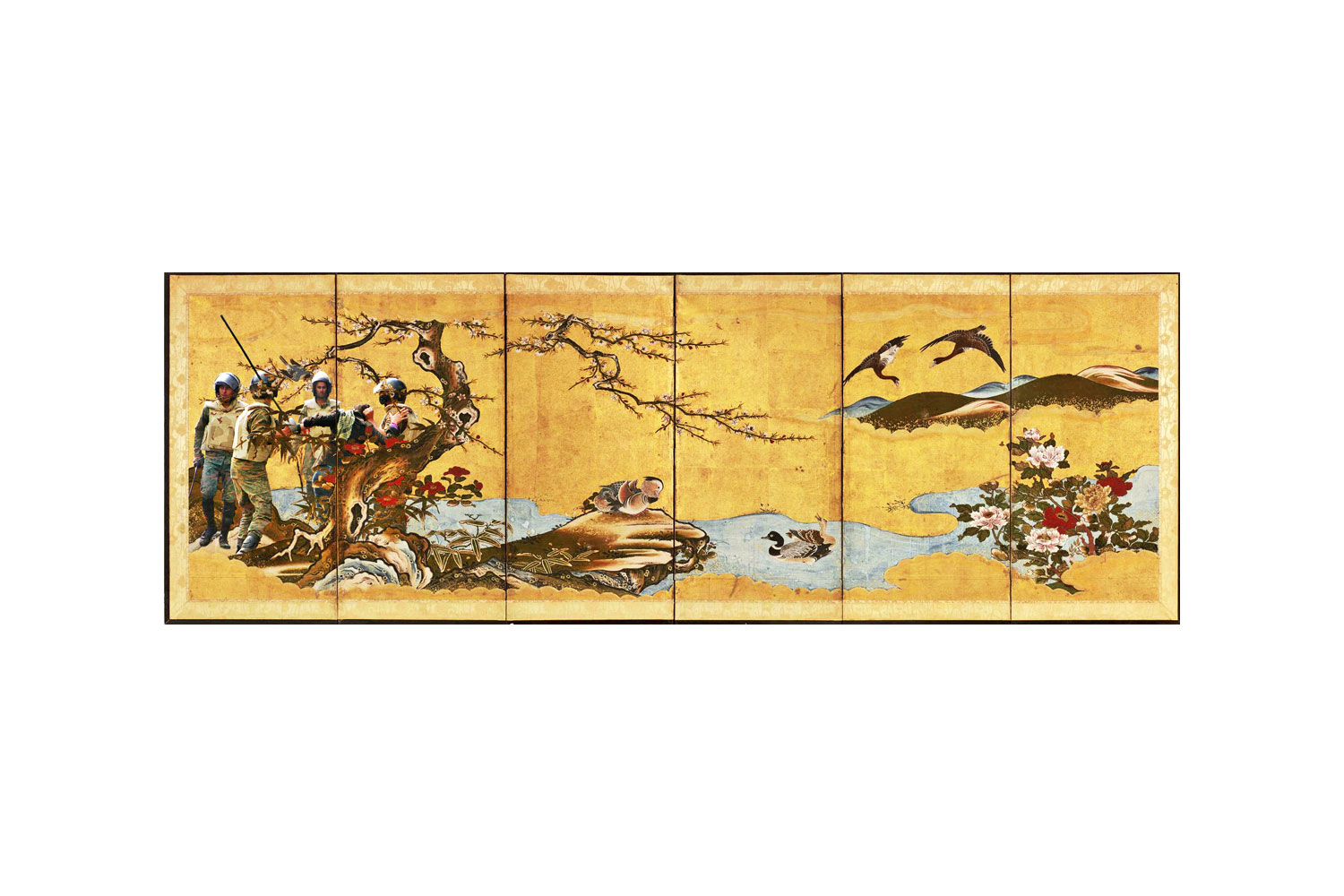

“unfolding” is a series consisting of 20 images depicting stylized Japanese landscapes, intersected with explicit footage of police and army brutality in the year following Egypt’s 2011 revolution. Inspired by 17th and 18th Century Japanese screens, the work is printed on rice paper. The photographic material incorporated into this work was not captured by myself but was collated by the from public sources, captured by Egyptian citizens in the months following on from revolution, and widely circulated through the media, Immediately recognizable to Egyptians, these images have acquired an iconic status in the country, becoming symbols of the waning revolutionary ideals that have given way to armed battles in the streets surrounding Tahrir Square.

The concept originally evolved from a personal experience of a day in Cairo where I witnessed young Egyptian protestors losing their lives in Tahrir Square, while less than one kilometer away, city life progressed undisturbed. The experience affected me in ways I couldn’t really pinpoint or find an appropriate name for. Many around me referred to it as the ‘twilight zone,’ a place where little sense can be found, where the expectations that structure everyday life oscillate between the absurd, the nauseating and the necessary.

Parodying the human urge ‘not to see’, I beatified these scenes of brutality, suspending images of unrestrained violence against unarmed civilians within aesthetically pleasing and highly stylized landscapes. In the foreground we see only the beauty of this utopian setting in all its blissful and ordered abundance. But peering through the undergrowth, we are unexpectedly confronted by horror. As though in a nightmare, we are diverted from the comfortable admiration of beauty, to become voyeurs of boundless violence and sadism, the very act of viewing confirming our acquiescence and complicity.

In this work I question our ability to blind ourselves to violence through distance and perspective. I try to probe the power of the mass media to entirely detach us from horror through the endless replication of imagery. The way it transposes us through infinitely layered images, away from the original act of crime, or sin, allowing us to live, comfortably removed, in a web of codes and signifies – or simulacra – that pose as reality but is questionably devoid of the real. The layers of the work signifies the noise of life that blinds us to the pain, suffering and the murder that lurk behind the endless parade of images we consume. In fact, it is the very act of creating iconic images that detaches, and desensitizes us from the original violence that it depicts.

The sensation had a common tonality to it, a familiarity that recalled times and places far removed from Tahrir. Most of us have experienced this feeling when, for instance, at dinner or in a cab on the way to some joyous occasion, an impersonal TV screen hurled distant images of starving children, of war, of petty criminality. Suddenly, all the absurdity of our daily lives comes crashing against these images, into a pool of generalized anxiety. At other times, we just turn our gaze away, or the TV off, not ready to deal with the thoughts that flow in the aftermath.

The pain of others can become the subject of crisis, avoidance or repression, but more often than not it simply ends up generating an alarming form of fatigue. [Susan Sontag] How many times could we relive the death of this cancer patient, or cry for this soldier left behind enemy lines? How many times can we gasp in horror at desperate New Yorkers jumping off of a World Trade Center? How many times can our guts squirm as a US embassy van speeds through a crowd of peaceful Egyptian protesters?

When someone actually dies, they only die once before the feeling of loss makes room for mourning. When they die on camera, their death is distorted in the endless loop of infotainment, and the spectacle of their pain grants their agony a perverse form of immortality. It is precisely this iconic immortality that we cannot deal with very well, as humane viewers who tend to identify with the pain of others. Images on repeat build our emotional immunity up, a shell that threatens to cut us off from our humanity, our capacity for empathy. And so, we must look away, or stare unending pain in the eye and become monsters.

Japanese screens allowed me to play around with these uneasy feelings, and also, perhaps, to understand my role in the industrial production of sudden shock then generalized indifference. The aesthetic distance they provided, that of Japanese good manners and taste, allowed me to gaze at the minute horrors of military rule without feeling robbed of my humanity. This wasn’t the political reality happening in my backyard; these scenes took place in a far away land between medieval Japan and contemporary Egypt. A fictitious space close enough that I cared to look at it, and far enough that I didn’t have to be moved by it. In other words, I was just looking at art.

This breathing room the screens grant comes at a price, for distance entails irony. By framing scenes of shocking pain, the Japanese screens also served to question the artistic industry forming around the Revolution, the paradoxical desire to stare, fascinated, and to look away, nauseated, the simultaneous longing to scream and remain silent. More generally, they problematized Art, the technical magic that renders suffering into a pleasurable aesthetic product of consumption and trade, thereby establishing an explicitly sado-masochistic relation with the audience. Enjoying my work became itself an act of sadistic violence for it entailed taking pleasure in the suffering of other humans, finding it interesting, provocative, decorative or appealing.

Unexpectedly, however, it was in this irony, the parody, that I found the greatest form of respect for my subject. How could we represent nauseating violence without rendering it toothless, without giving birth to disposable, single-hit wonders? Was there a way of depicting violence without making pornography? Pornography brought to life vivid images of a societal taboo, physical intercourse, in a way that ensured a certain fascination quickly followed, after consumption, by flagrant disinterest. Keeping desire and lust alive, like maintaining the pain and suffering, entailed the opposite of revelation and full disclosure: it demanded suggestiveness. Violence had to be hinted rather than divulged, the point of impact had to remain half-hidden from view—censored behind polite foliage—and half-obvious from the dynamic interaction of the protagonists, the movement of the batons or the looks of incomprehension and shock on victims’ faces. Respect demanded that instant gratification be neutralized. It must take some effort of the gaze for the viewer to realize the actual horror of the situation beyond the placid surface, to fully absorb the brunt of the shock.

The censoring of the screens eroticizes the violence; it saves these images from the banal pornography of their daily circulation. Paradoxically, it redeems their power to interpolate us by putting some distance between us and the horror, by neutralizing the usual knee-jerk reactions of empathy that immediately deplete these images of their capacity to move us. This ambiguous politeness of art keeps the pain of reality alive. Its lightly concealing refinement keeps reminding us that what is most violent is also what is most revealed: the way in which we are constantly force-fed pornographic images of suffering, in the name of empathy, that turn us into monsters. That somehow by seeing it ‘like it is’ we are more responsible citizens of the world. They remind us that perhaps we should set aside our antiquated notions of realism and photojournalistic accountability; that some forms of artful, artificial representation remain the only way to portray violence without sadistically violating the victims that we focus upon.

FAUNA

26 X 20cm

The River I

16 x 48

Hibiscus

26 x 53 cm

Codes of My Kin

25 x 53 cm

Sweet Spot

21 x 53 cm

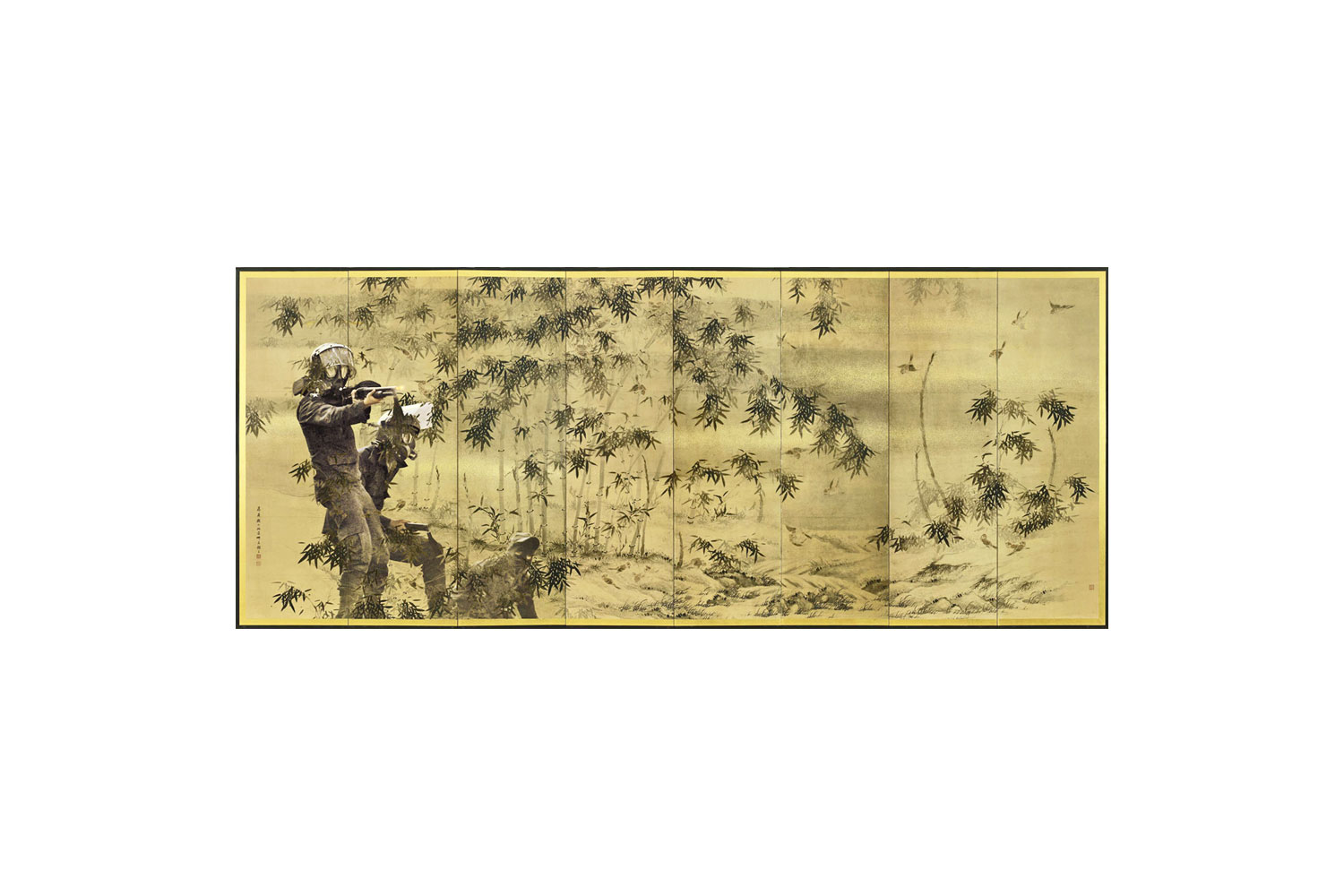

The Hunt I

23 x 53 cm

Escalate

38 x 52 cm

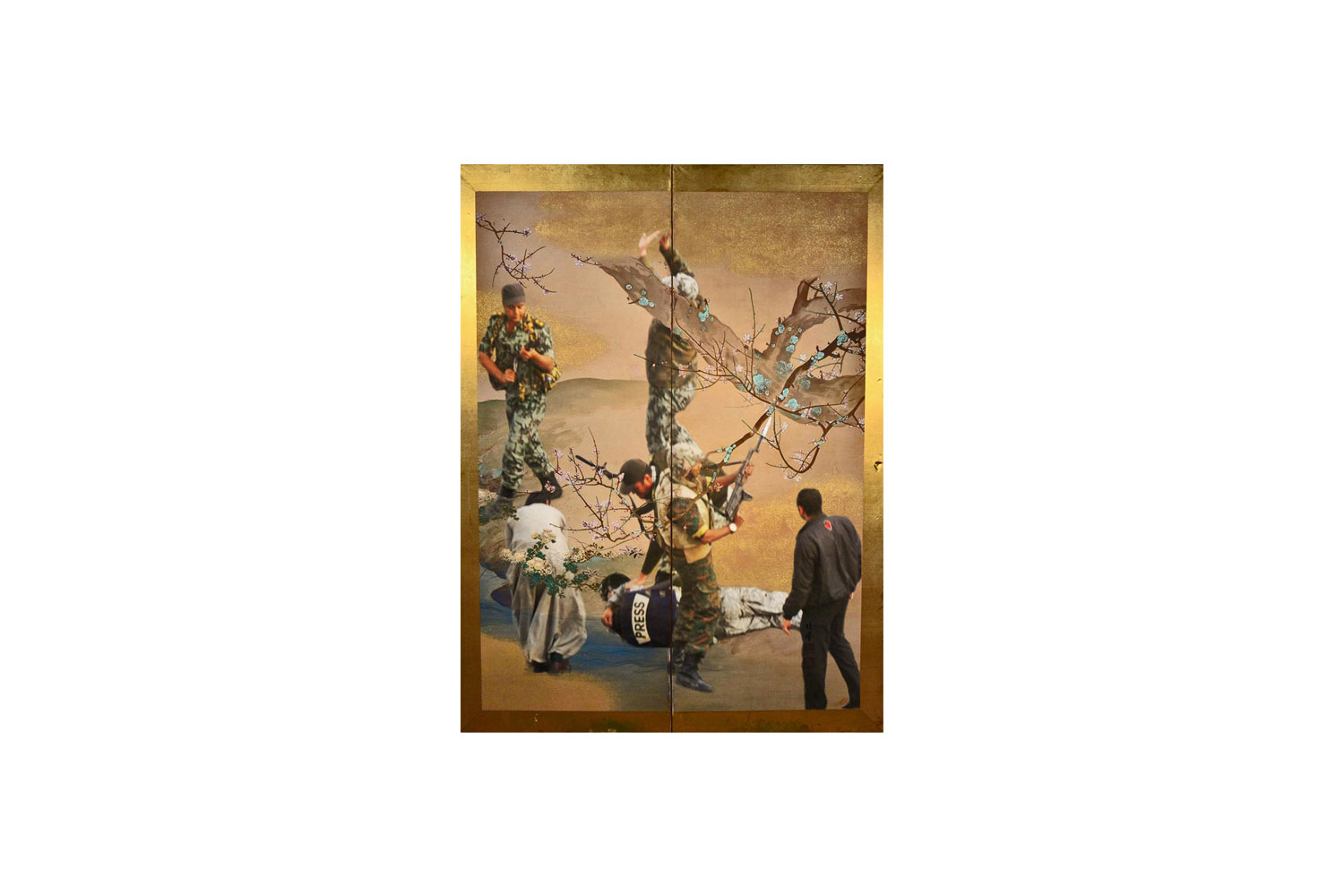

Press

19 x 25 cm

Myopia

24 x 53 cm

The Camels' Flight

40 x 83 cm

The Hunt II

20 x 53

Hitch-Hiking

37 x 52 cm

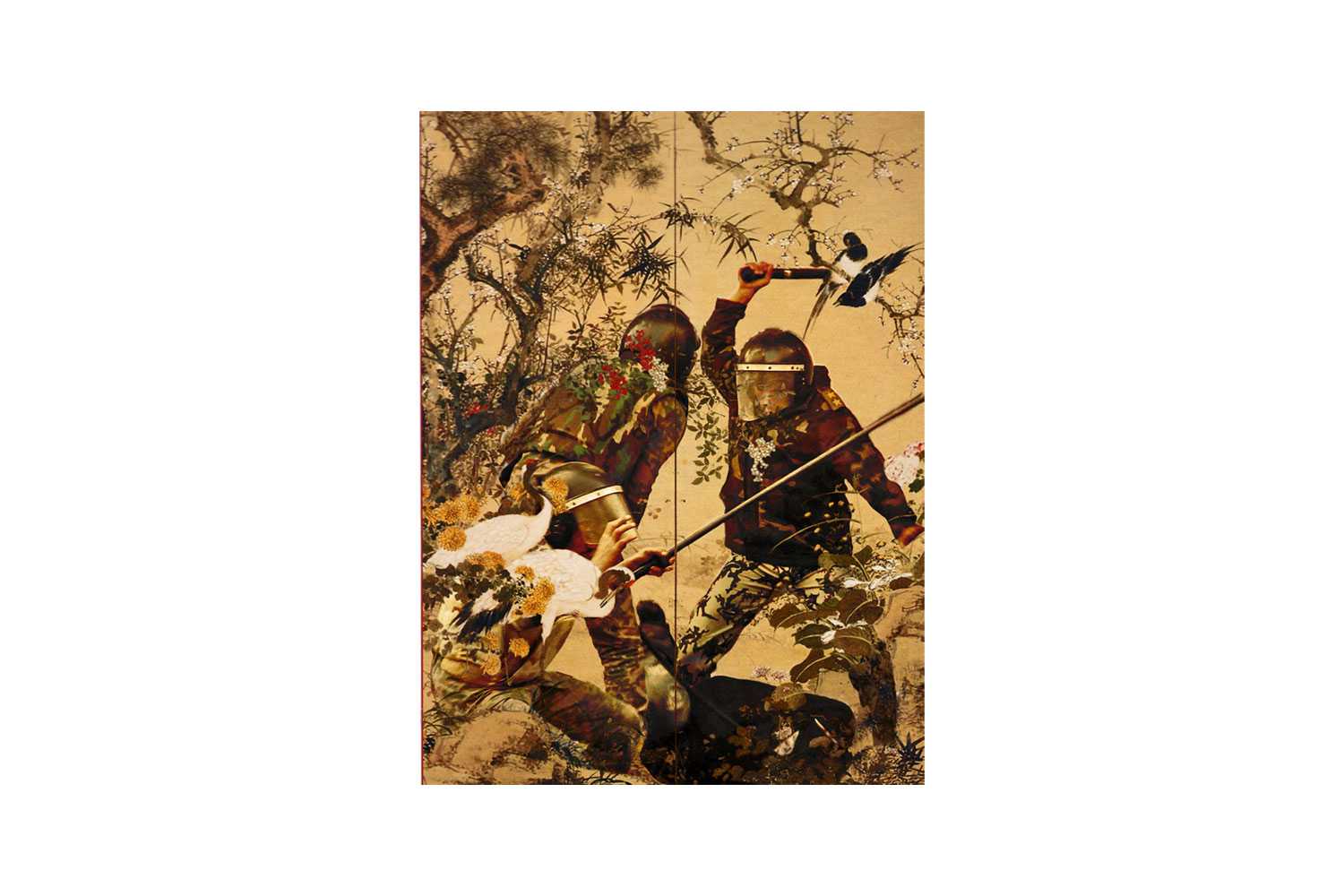

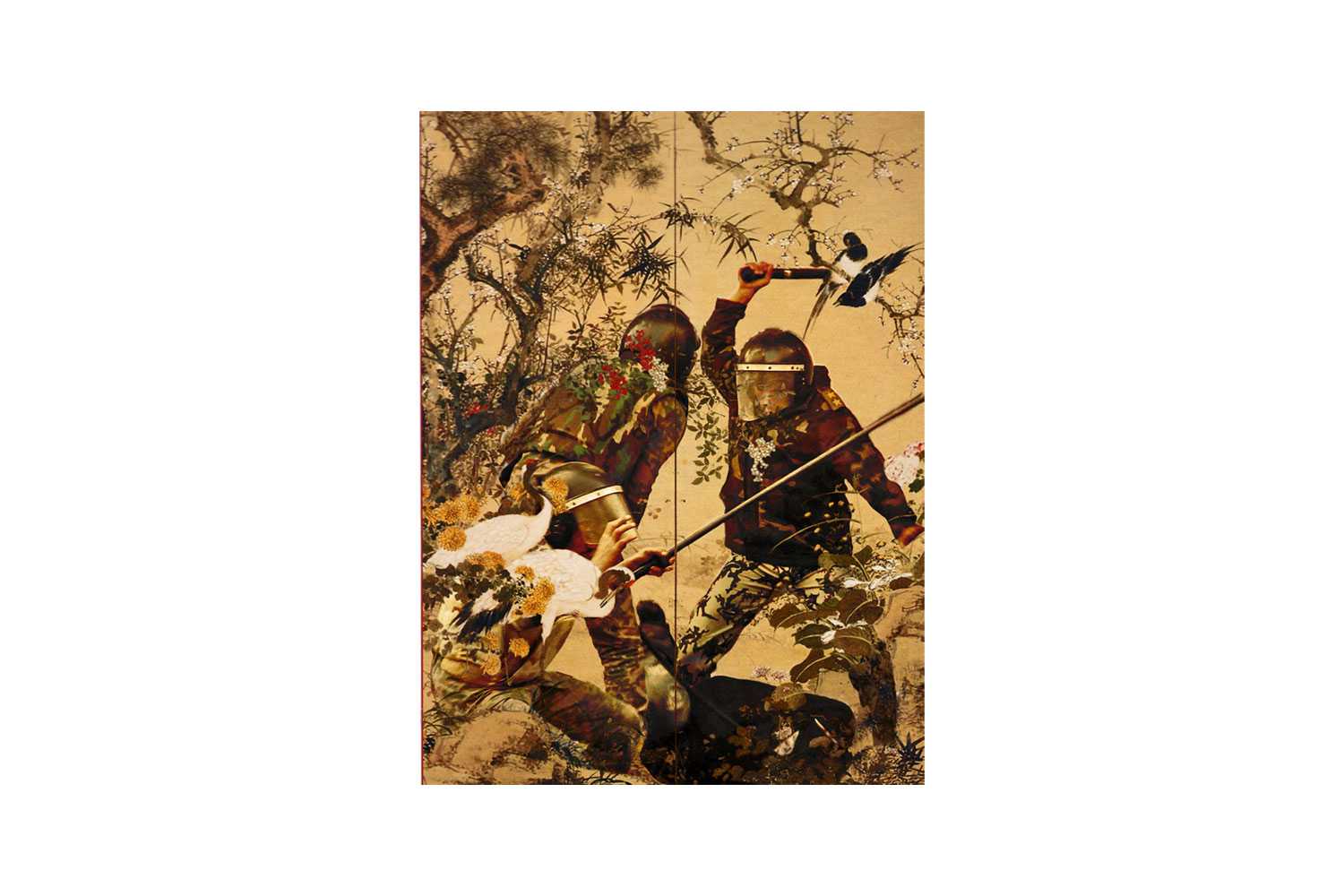

Hell in Eden

28 x 56 cm

Aat posuere sem accumsan nec. Sed non arcu non sem ch5mmodo ultricies. Sed non nisi viverra

53 x 48 cm

A Leap in Faith

22 x 53 cm

Super Gardens of Tahrir

17 x 53 cm

The Battle

20 x 53 cm

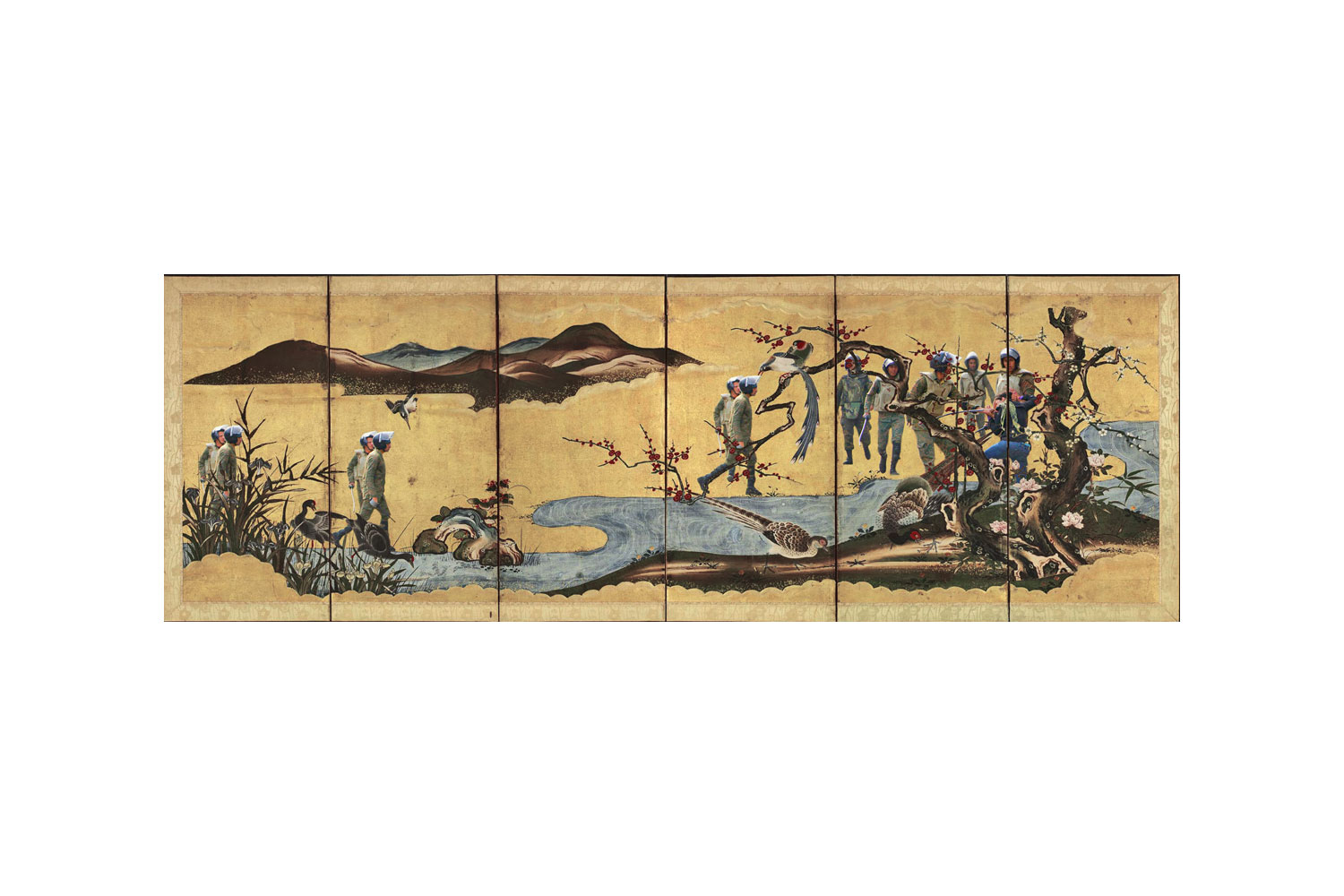

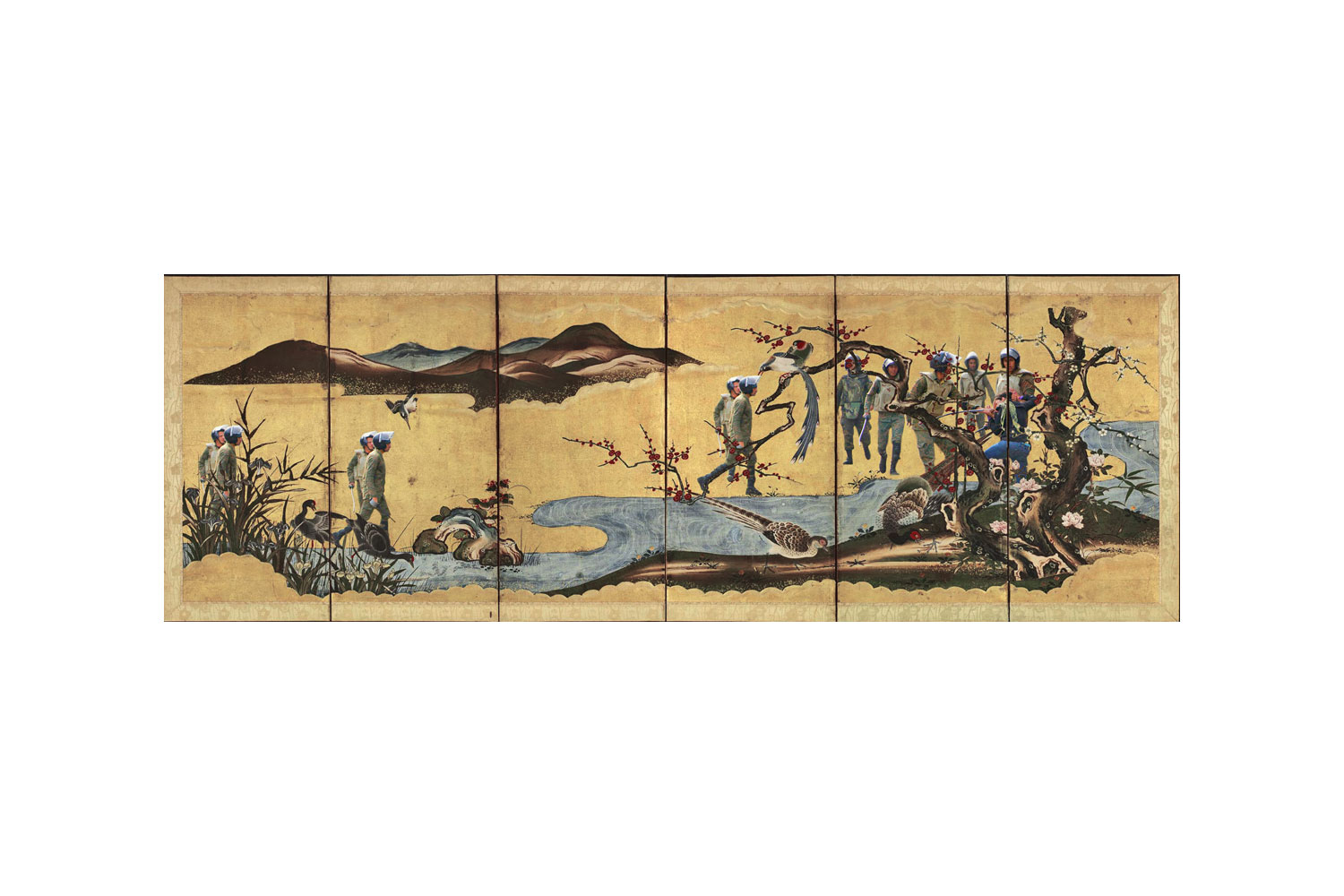

War in Peace

25 x 53 cm

Lions of the Square

53 x 25 cm

The River II

17 x 49