Cosmos

Installation

Cosmos Artist Statment For the Ancient Greeks, Cosmos – the harmonious order of the universe – stood in antithesis to Chaos – the formless void preceding Creation; a chasm keeping Heaven and Earth apart. Like many other ancient words, Cosmos had multiple meanings: “good behavior”, “style”, “government”, “honour”, “ruler”, “the known world”, and “men” in general. When applied to women, however, Cosmos acquired a meaning very far from these manly ideals. It meant “ornament” or “decoration”. It is in the order of the universe and the details of individual ornamentation, in this early dichotomy of ancient definitions and the incongruity of Man’s age-old tendency to wor- ship the images of his own creation, and to trust in the transitory powers of hollow ornamentation to ward off his ultimate descent into “Nothing” that my work, Cosmos, has its roots.

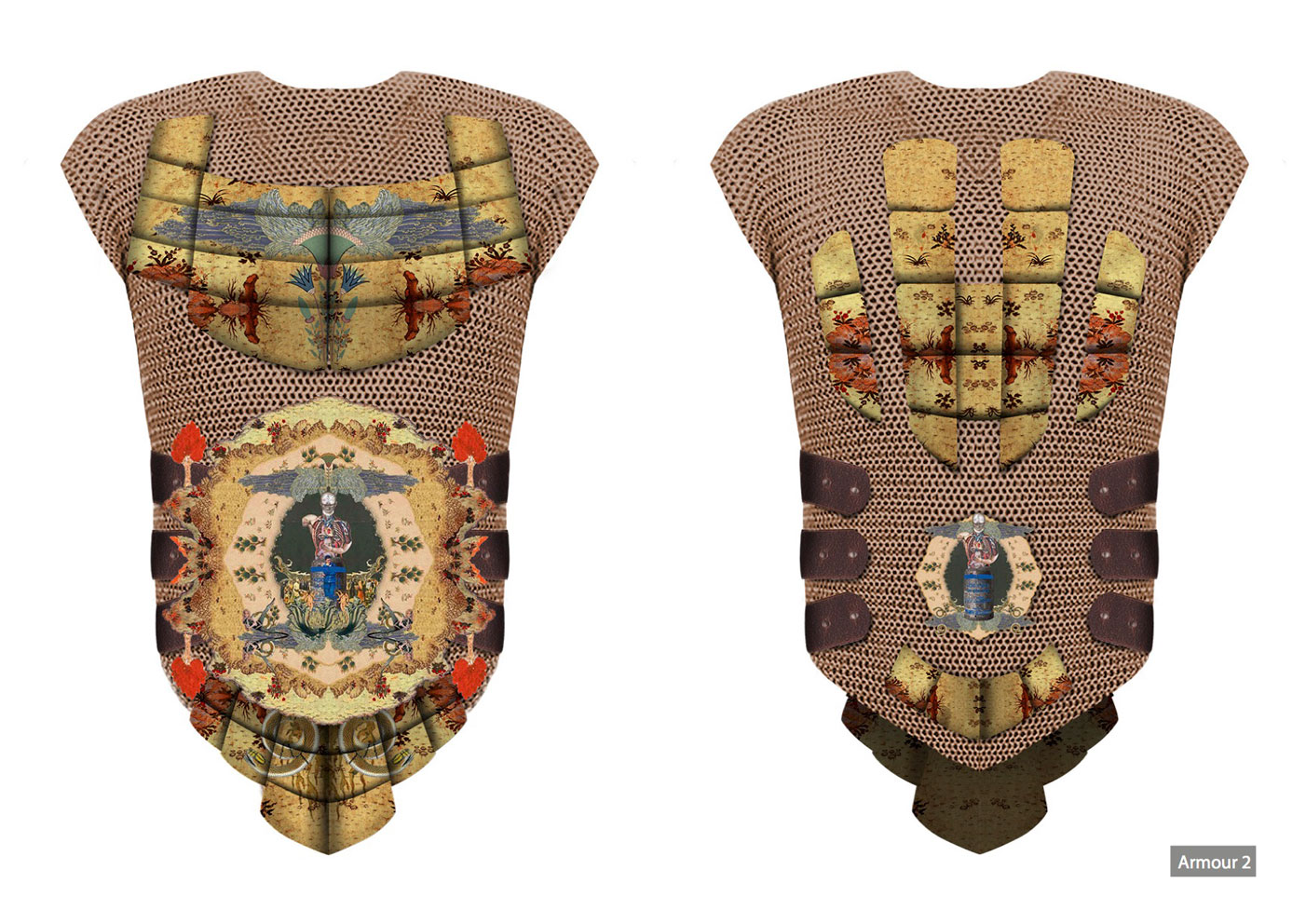

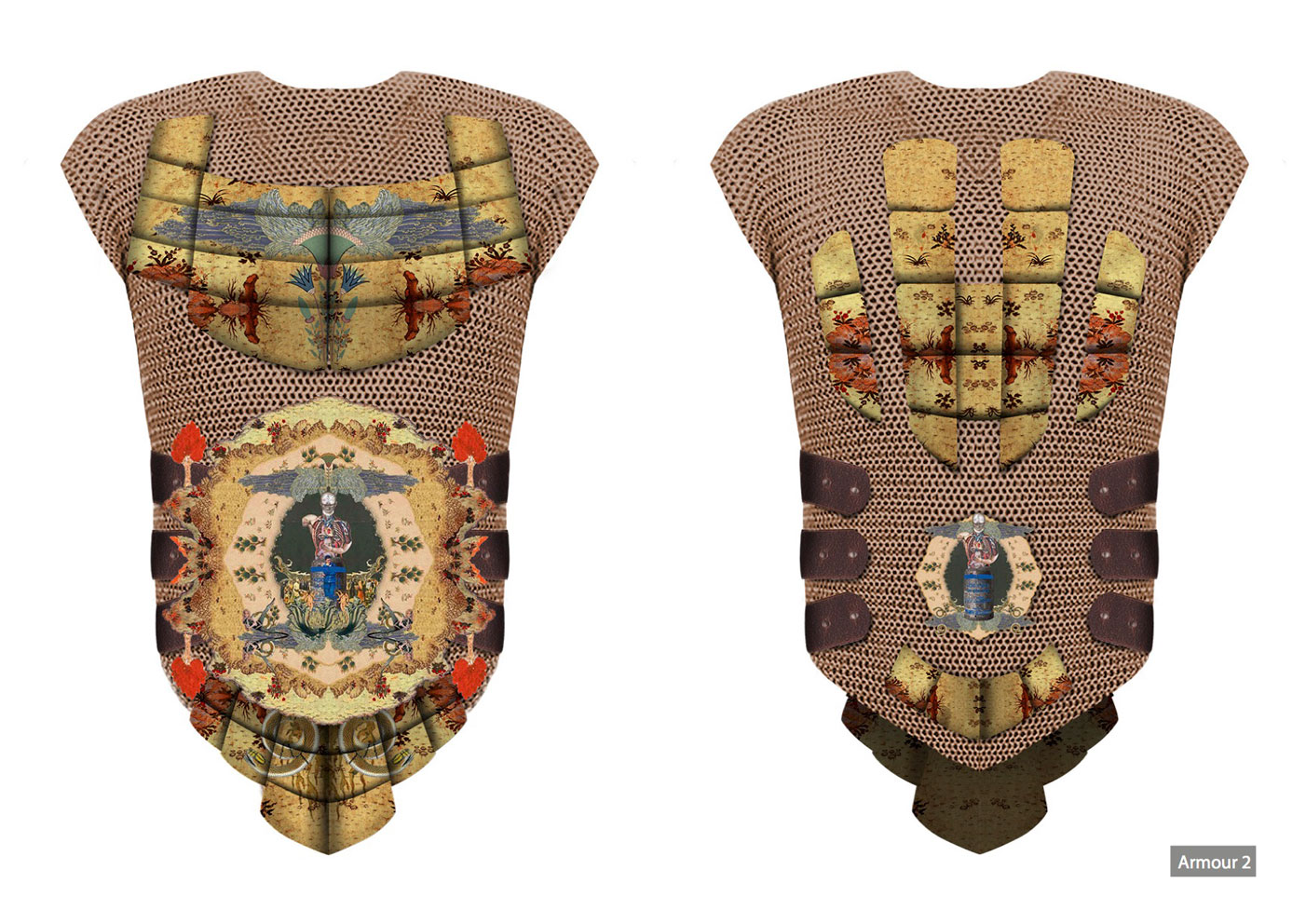

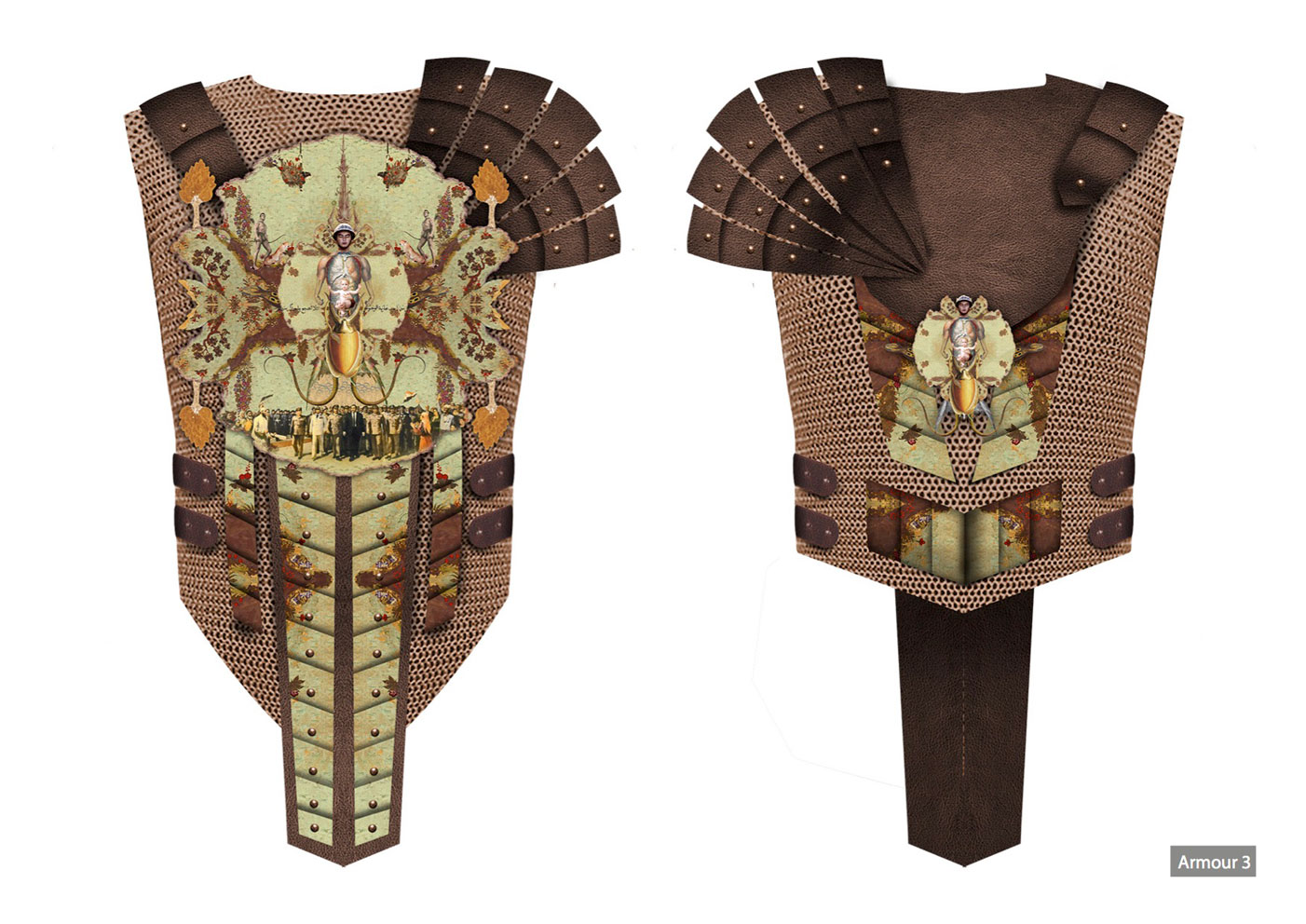

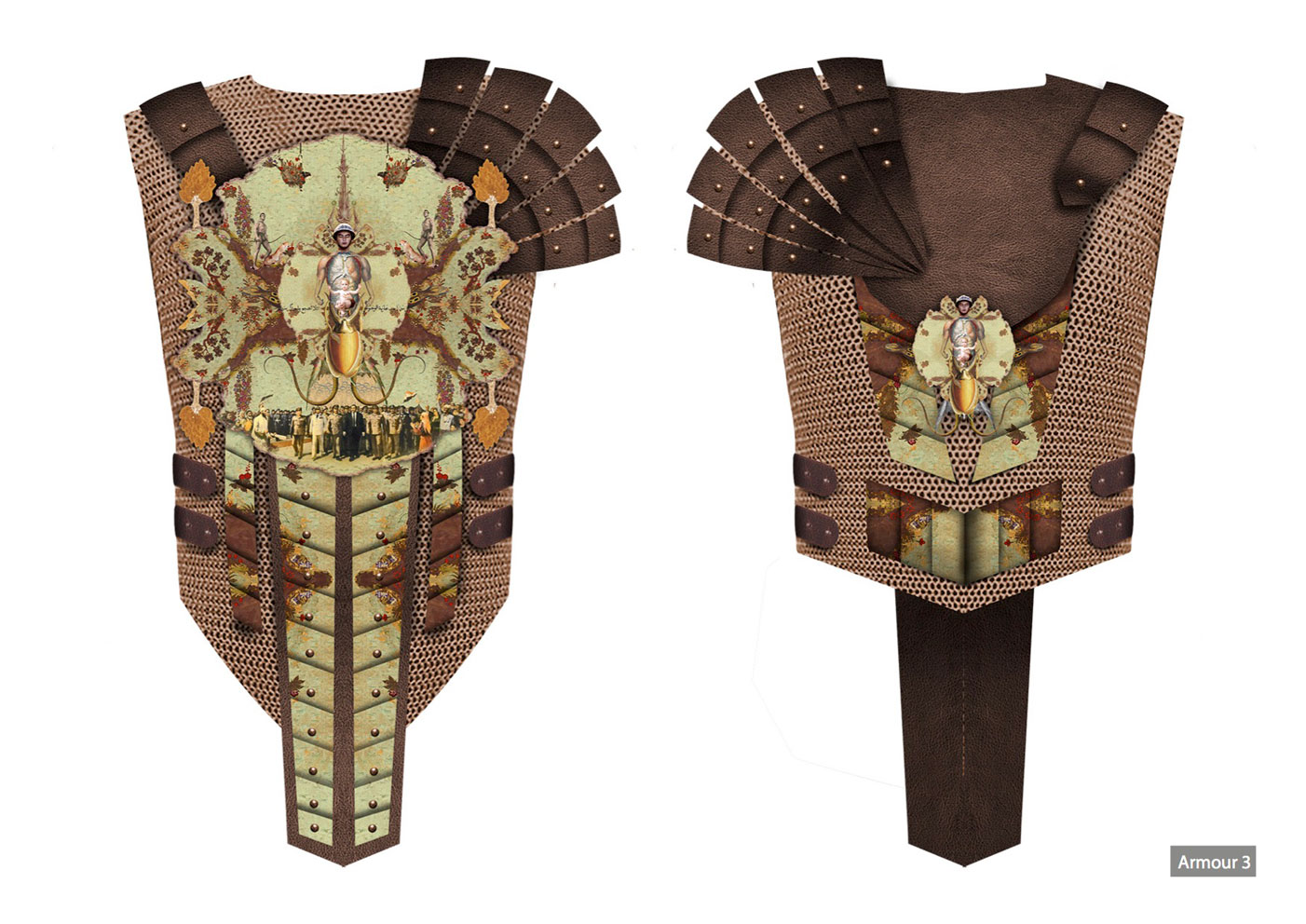

Cosmos is an installation of seven hollow hand-made suits of armour, made from chainmail, leather and ceramic fragments. These objects of masculine virility are not meant to impart a sense of physical security but rather to highlight notions of frailty and ephemeral beauty. These sumptuous, yet empty, suits are testament to the frailty crouching behind military prowess. They emphasise the aesthetic nature of warfare, its ritualistic elements and theatrical processes. These most intricate and beautiful ornaments stand at the juncture of the horror and artistry of warfare. Any protection they offer is only symbolic, like a talisman, disguising the horror of war with a layer of vanity. Perhaps the fact that shields have always been decorated is a way of shielding us from the horrors of war.

Behind the installation of the armours an image of a lone soldier/hero floats, spectral-like, against a backdrop of shimmering gauze, fleeting and ephemeral beside the silent forms of armour.

The cosmos and warfare

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.” From “The Second Coming” by WB Yeats

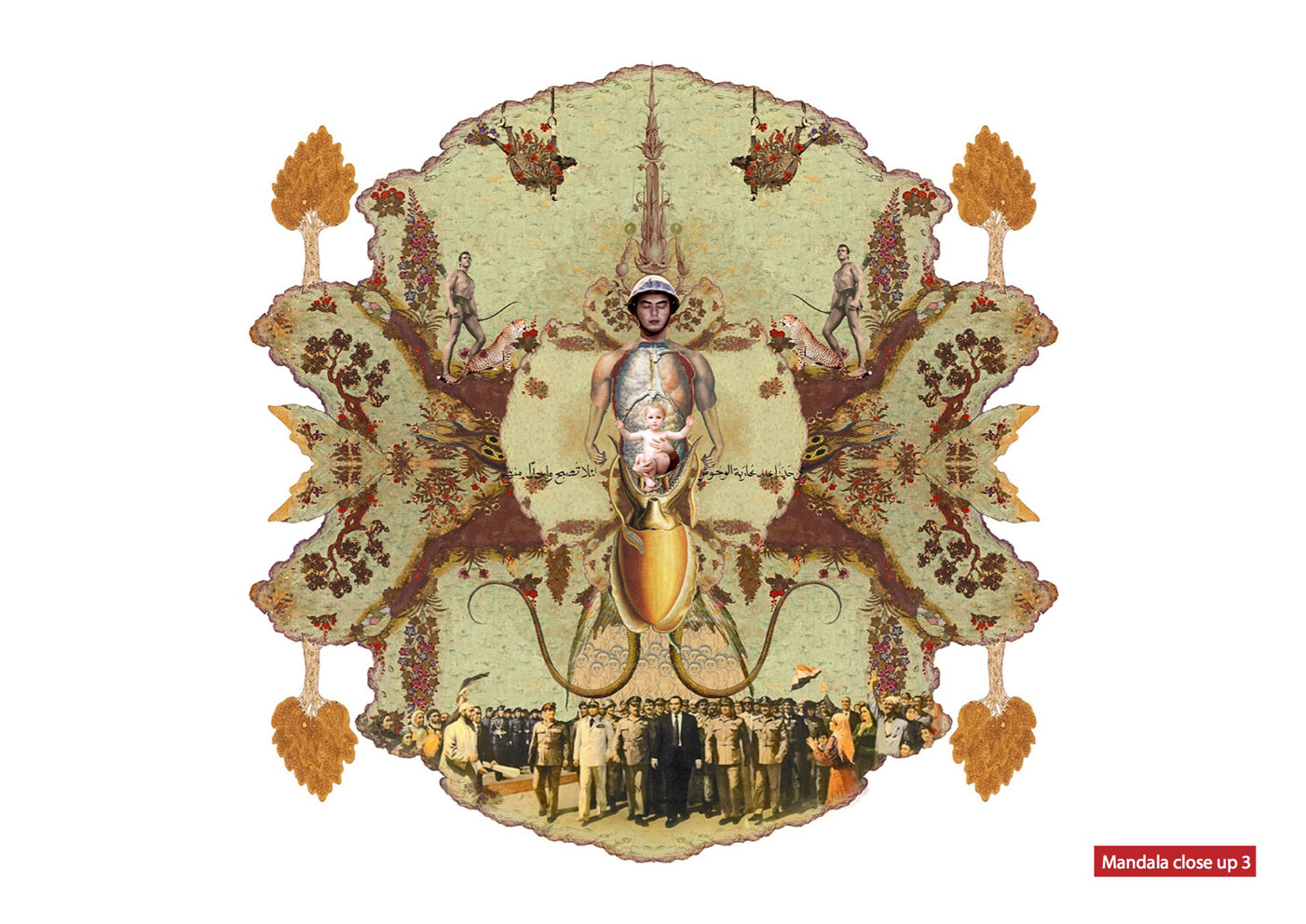

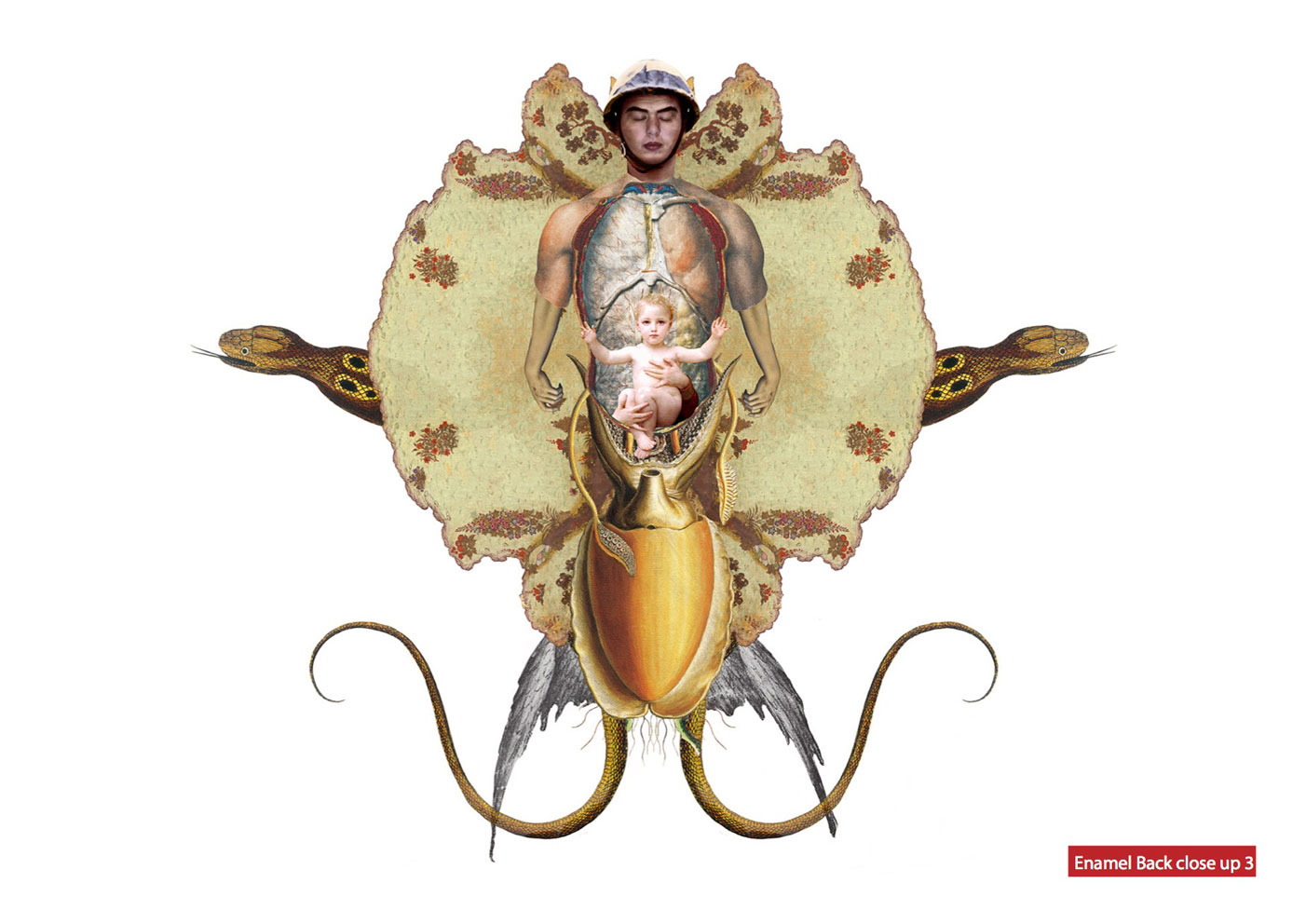

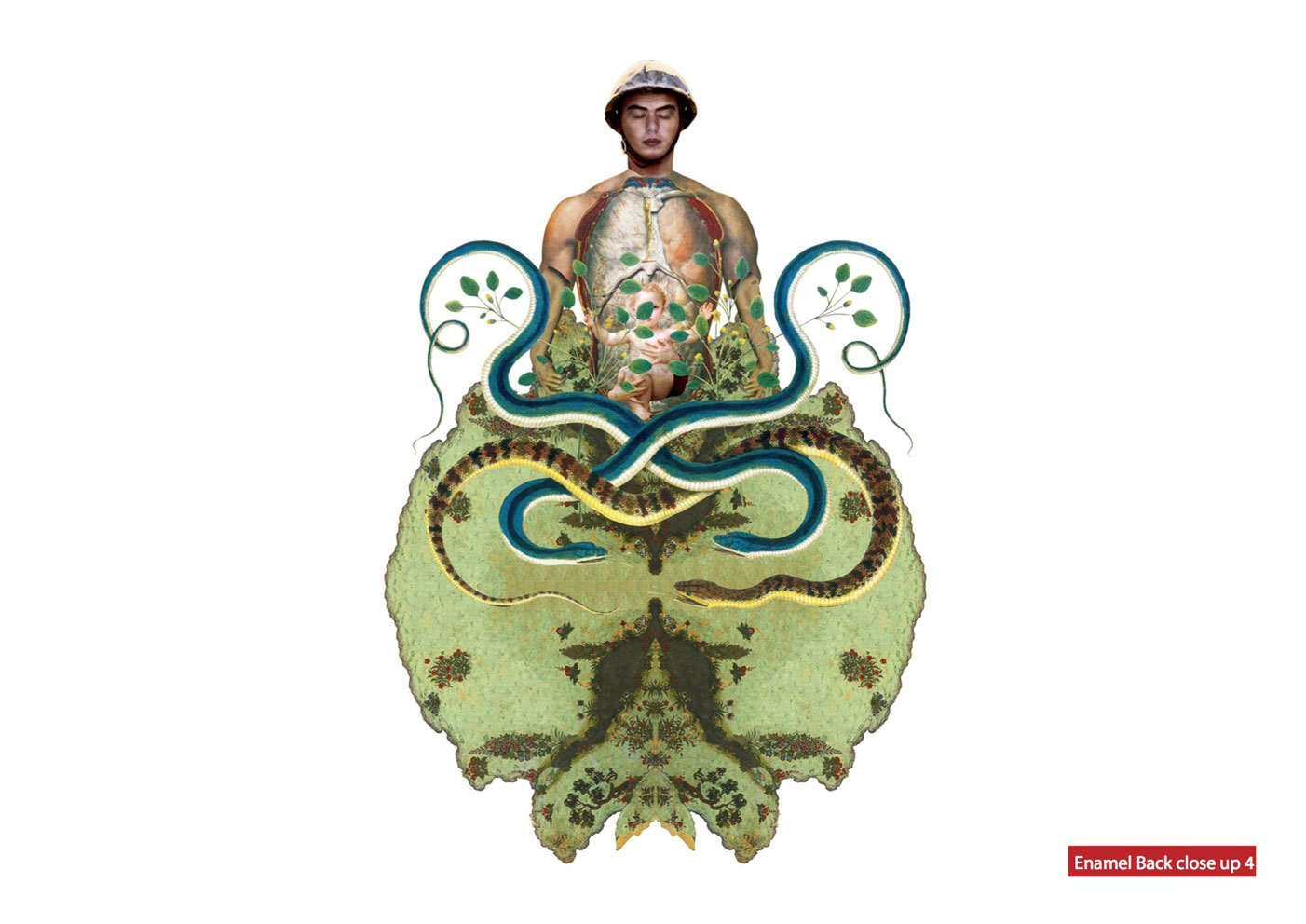

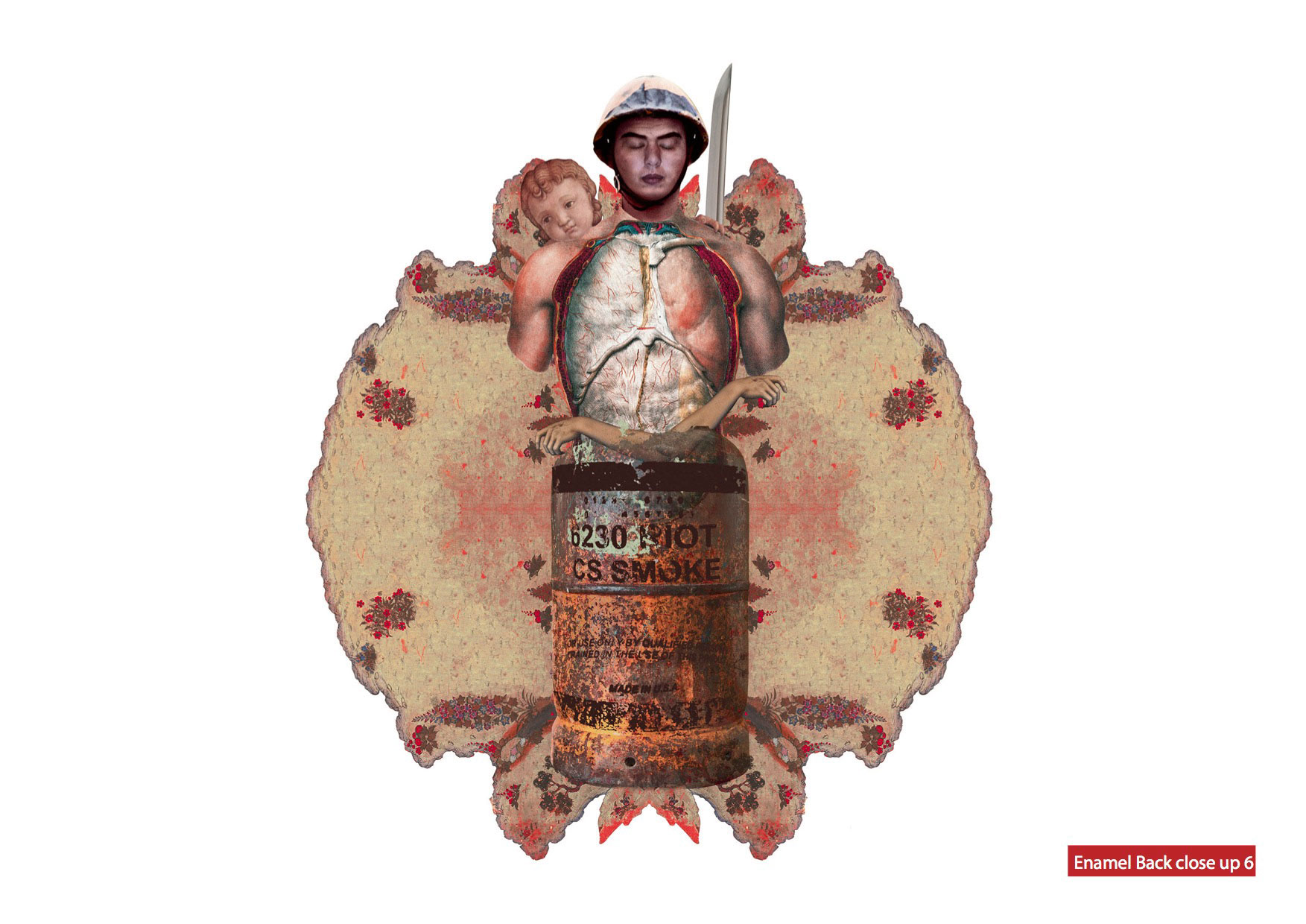

Each suit of armour has a decorative mandala, which traditionally represents divinity, the twin pillar of the self and the universe. Thus the true nature of reality appears as the self dissolves into the universe; the part into the whole; the ornament into the cosmos. The cosmic truth hidden in the geometric patterns of the mandala provides a pictorial representation of this recurring theme of mythological and scientific thought: that the birth of the individual mirrors the birth of the world, genealogy flowing from cos- mogony, and that the evolution of the organism mirrors that of the species, morphogenesis following phylogenies.

However, the heterotopic space in Cosmos explores the collapse of the universal order upon the intimate details of the personal. The refracting four-gated circles within the squares of the mandala offer a miniature repre- sentation of the cosmos. Cosmos does not have a centre where the forces of the universe rest in balance, rather the contents of the mandala are chaotic and kinetic – they do not allow the viewer to turn inward and experience that place where unity, infinity, transcendence, timelessness and Absolute Being can be experienced. Here the absence of a centre leads to a disin- tegration of the world. When the cosmic axis or axis mundi disappeared, mankind regressed into Chaos, a time before Creation. Anxiety and despair marked the falling away of the world into non-existence. Within this space of broken self-exploration and self-actualisation we find a soldier, the hero of the work. Yet he is a broken and depleted hero, disfigured, with his insides exposed for all to see and his lower body is missing. Instead his bloodless torso strapped to a tear gas canister, his eyes closed perhaps in meditation or perhaps in death. His body is fragmented and dismembered and when reassembled the parts do not fit, they are maimed and atrophied. He clutches a small child that is, in fact, himself. A talisman of our times, the mutilated hero is a symbol of the violence Man inflicts on the icons of his own creation. We are locked in a cycle of maiming and destroying, putting our heroes off center in a relentless quest for life beyond death, and for form beyond formlessness. The assorted pieces form a mandala to create wholeness and individuation, yet highlight what is crippled at the centre.

In this sumptuous kaleidoscope of impressions, icons of gender flash before us, then become meaningless and dissolve from view without propelling us to an ultimate conclusion. With these armours, I pay tribute to the sumptuous aesthetics of the manmade ornament, even as I recognize that beauty cannot stand between us, and, non-being. Chaos is a state without images. Our lives, and the narratives that define them, are little more than images papering over the void.

Cosmos is the story of a world where the correspondence of the part to the whole, the harmony of the self and the universe, has given way to perpetual conflict. No resolution can be found at the centre of these war- themed mandalas, which are anti-mandalas. Instead, their centre is empty, displaying the ultimate realities of modern subjects – a dense impression of figures and symbols, existing in a single moment, refuting manmade notions of linear time. Mutilated or fragmented bodies, cannon-fodder, children with weapons, innocent hostages to a ticking time-bomb. The ancient Egyptian symbol of the soul hovers about the lions of Tahrir Square, oriental dancers and Hollywood starlets crowd the space, interspersed with political leaders, and crowds, all against backgrounds of Persian miniatures: selfhood understood as the sovereign prerogative to dispose of life, the legitimate right to kill.

Within this cosmic order, the traditionally feminine ideals of peaceful harmony have been conscripted to the ego as killing machine. Like the mobs that carry war heroes to their untimely death and fragmentation through the promises of honour and glory, the female figures in Cosmos gyrate joyously, waving at the violent masters of the universe with promises of blissful earthly oblivion. Like Barbarella, the poster girl for feminist emancipation in the 1960s, the Cosmos women stare at us defiantly from the cen- tre of the universe as models of gender equality through their equal power to inflict death. Despite their adornments and dress, the killing machines at the heart of the universe form the centre of a world spinning off its axis. Perhaps, the ceramic shields of Cosmos represent the temptations of power; the temptations of individuation through war, bringing order by giving orders, structuring through commanding; the temptations of a world founded on endless cycles of domination and destruction, and threatening to be swallowed by its own chimerical tensions, intertwining snakes, or dying elephants. The spectacle of this tempting picture fascinates as much as it repels, invites as much as it forbids. The shields of Cosmos, held not by humans but by spears, stand in a vacuum, devoid of human life, which has been exterminated by the Apocalypse it fabulously announces. Ironically, like other objects of consumerism, these fragile and horrifying tributes will outlive us, bearing witness to our world long after our last breath. The world they represent is more interested in outer decoration than the cosmic cen- tre. What we see is the living decoration of a dying cosmos.

El Asad

El Asad Close Up

El Midan Close Up

El Batal

El Batal Close Up

El Batal Close up

El Wa7sh

El Wa7sh Close Up

El Wa7sh Close Up

El la2

El la2 close up

El la2 close up

El midan

el midan close up

El asad close up

EL GADA3

EL GADA3 CLOSE UP

EL GADA3 CLOSE UP

EL 3EIN

EL 3EIN CLOSE UP