Wetiko

Paper: Hahnemuhle Photorag Bright White 310 grams

OH, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet, Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God’s great Judgment Seat.

Rudyard Kipling, The Ballad of East and West, (1889).

The idea for this project first surfaced in 2013, after two years of traveling between the streets of revolutionary Cairo and my desktop screen. The contrast between my daily experiences and the news reports was hard to ignore. In a sense, the revolution started with a lie. On the 25th January, most state media channels still insisted on pretending everything was fine under the placid sun of Egypt—showing us flowers, birds and “natures mortes” along the Nile, instead of burning headquarters and dying protesters. A few months ago, in the aftermath of the Rabaa massacres, I witnessed groups of men staging the events of the preceding days for visiting Western photojournalist—who eagerly posted such reenactments as pictorial truth.

Such occurrences have punctuated the Arab Spring from its inception. Photos of dying masses in Iraq were used to picture the horrors of the Gaddafi regime in Libya; an allegedly Syrian orphaned girl lying in a chalk drawing of her mother’s womb turned out to be school kids posing for a professional art project, a few thousand protesters on Tahrir could be easily cropped into 30 million protestors, etc. etc. etc. And beyond even the Arab Spring, these instances of “strategic editing” were as old as mass media itself. We all still remember the video where Iraqi dissidents, in a supposedly spontaneous outburst, pulled down Saddam Hussein statue to the ground, and the immense staging operation that it had in fact required—visible right as we zoomed out of the edited installation the media had allowed us to see.

The interchangeability of victims in media portrayals, their second death, lay at the root of this project. Cropping, editing, self-censoring were all acts of violence to these subjects of history—unethical according to journalistic practice but necessary for the purposes of imperial warfare. My constant interaction with such micro-violations of truth and event for the sake of narrative led me to this reflection on the fabrication, manipulation and implications of political myths.

In his book Mythologies (1957), the French philosopher Roland Barthes explored humankind’s acquiescent nature in relation to myth. He understood that the conventional person (or ‘myth consumer’ to use his term) often accepts myth as truth, becomes bound by its language, and consequently may struggle to liberate oneself from it. It is significant to recognize how this process plays in the media and how it functions in modern-day thinking. Newspapers, radio and television broadcasts, propagandist groups and international organisations, all can easily stage or misuse images, manipulating our senses to aid their purpose. Hence the published image can no longer be trusted. The medium of photography, known for its unparalleled ability to capture realistic representations is often willfully employed and misappropriated by these parties to in fact alter reality for their desired effects. This is a common influence in today’s world, contributing to the control of consumers and the propagation of Wetiko societies as described by Forbes.

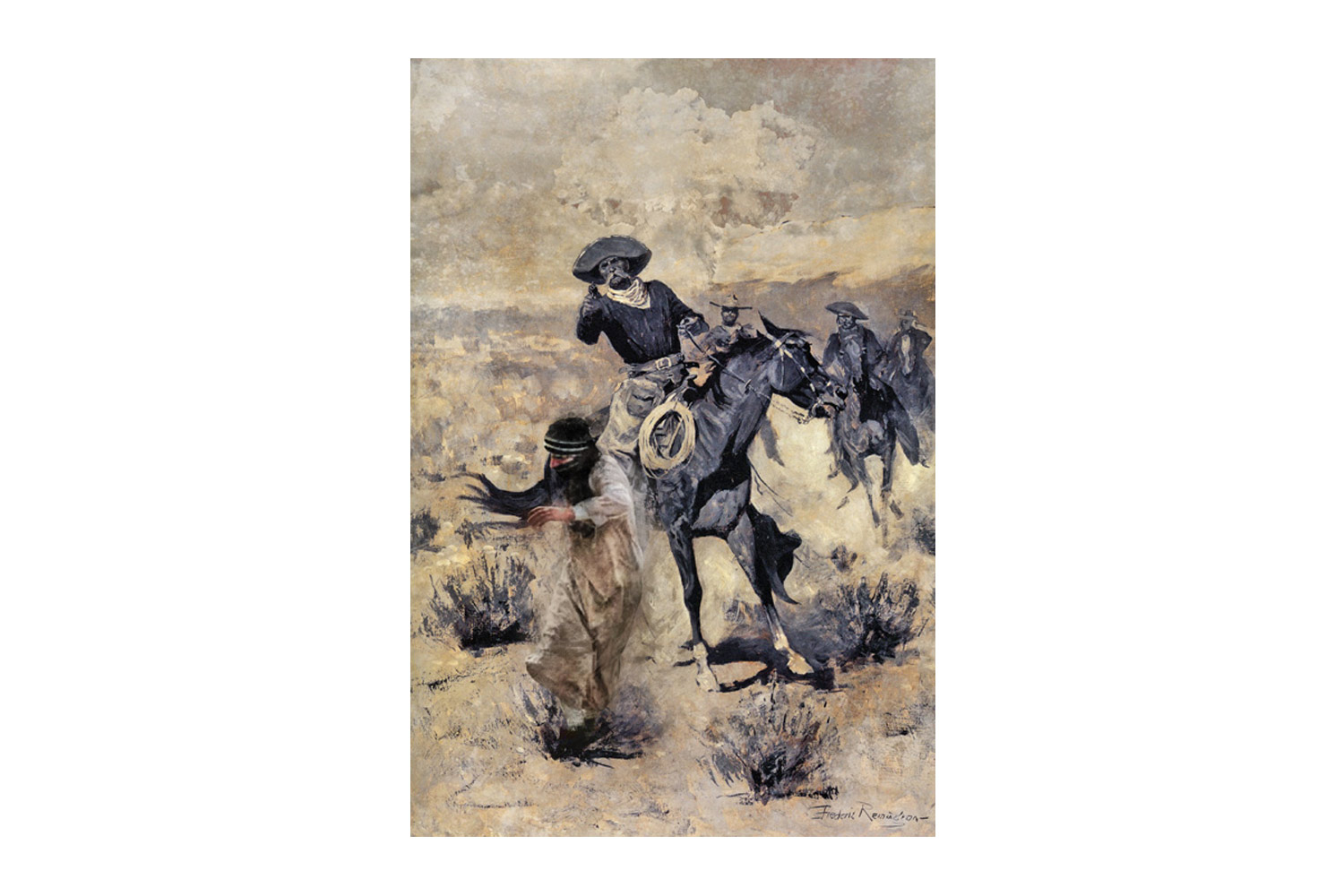

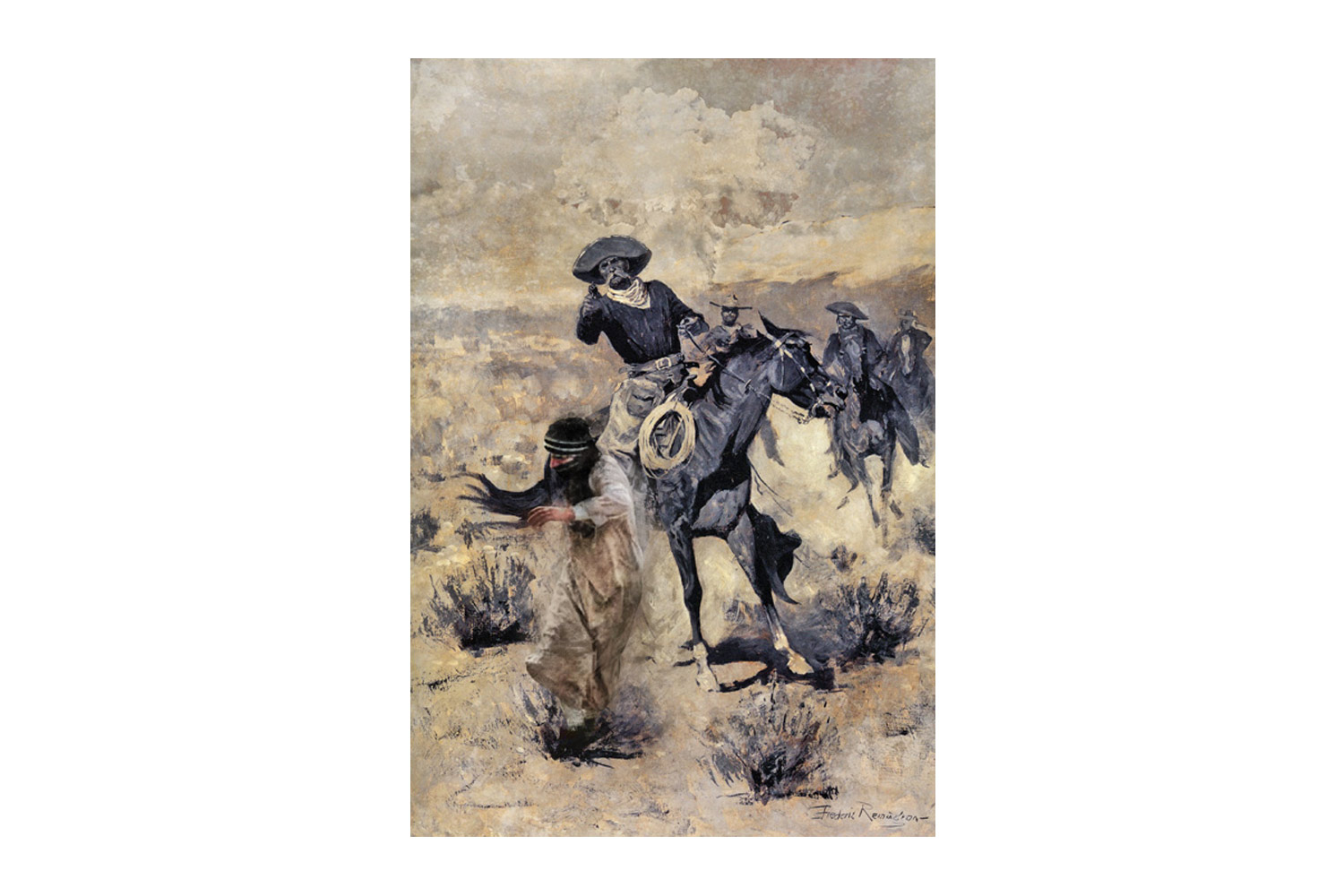

After my experience in Cairo, I began to see similarities between the mythologizing images of the artist-correspondents of the American Wild West (such as Frederic Remington and Charles Marion Russell) and the international community’s influence in the Arab world. In both cases, highly emotive images have been widely used to justify aggression. Drawing on these parallels, I wanted to create a body of work that reflected my observations while challenging our preconceptions. Art plays an important role in our appreciation of the nuances of culture and belief. Art can also communicate ways in which to deconstruct those nuances. With newscast propaganda as a clear example, if we change one element in an image, it can affect our entire reading of the scene. Correspondingly, if we replace one element with another, a story can be retold.

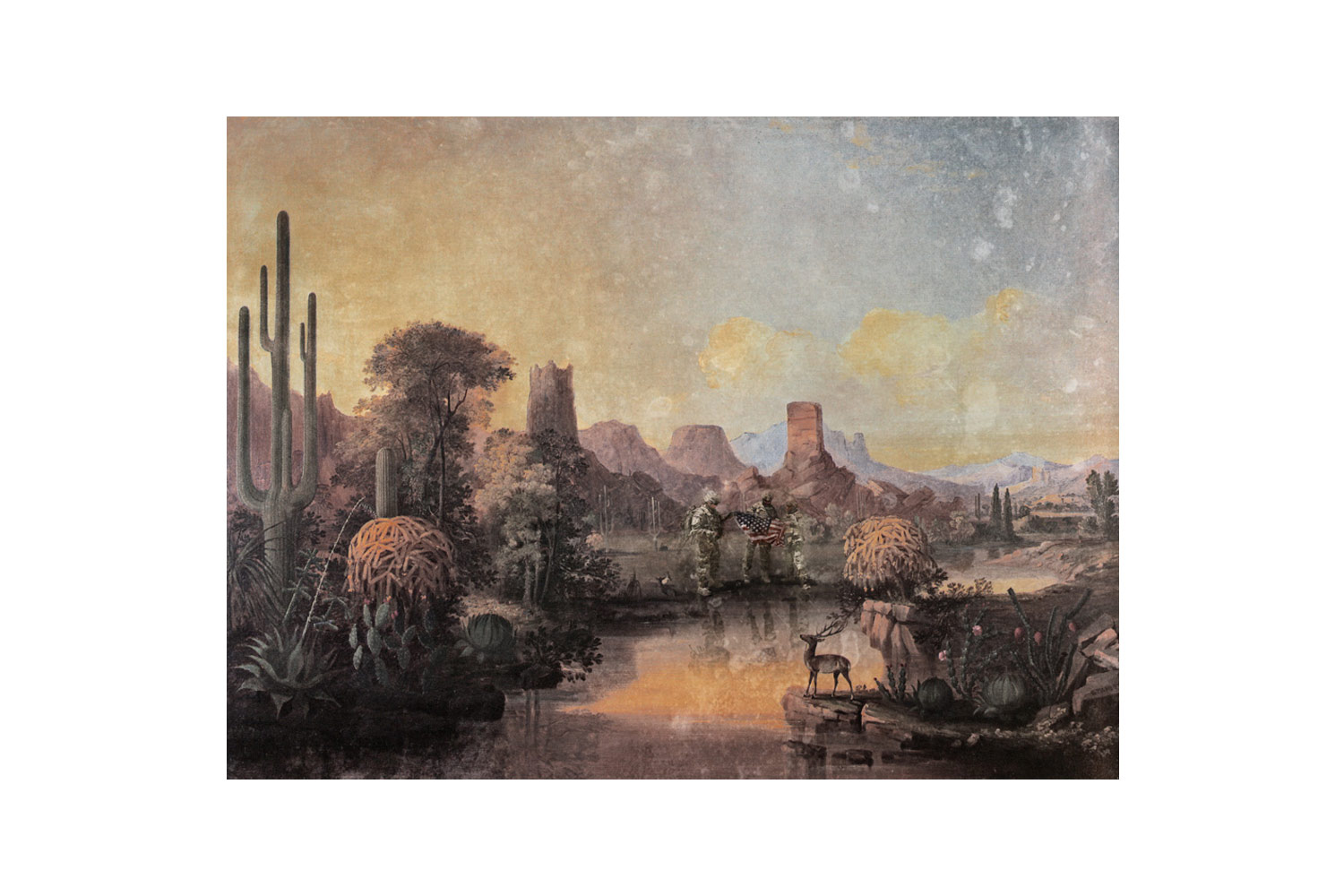

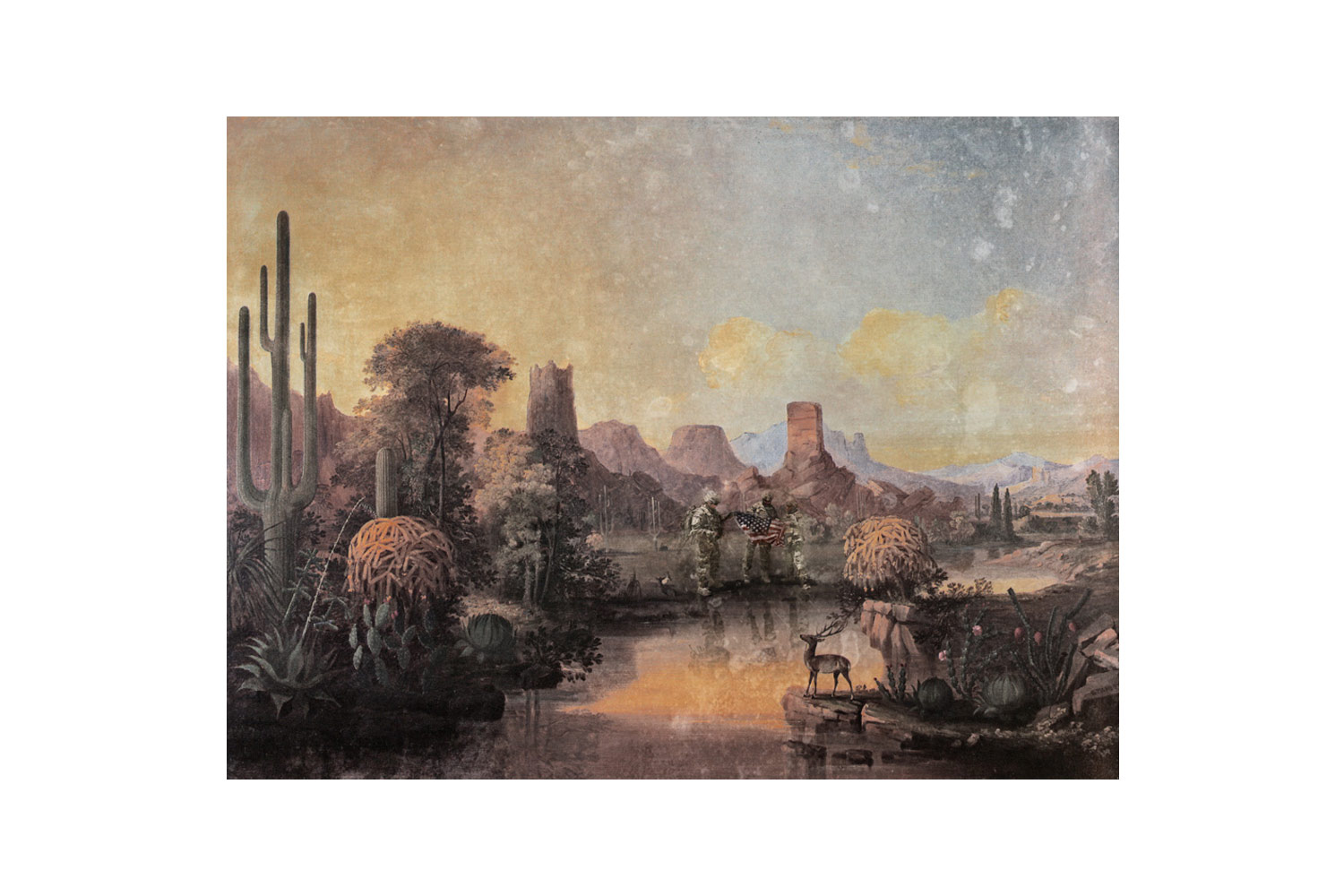

In Wetiko – Cowboys and Indigenes, I deliberately use a chronological juxtaposition of images, not only to heighten the absurdity of the situation, but also to mimic its realism and historic authenticity. Every image in the series envisages unfathomable and perplexing happenings. By incorporating modern elements and notable figures from history into famous paintings of the Wild West, the work becomes playful and provides the mythologized setting needed for the viewer to challenge the revised analogy.

The series comprises of nineteen composite images, divided into Orientalist and American Western paintings. The first step was to choose the paintings I wanted to use, which were then paired with contemporary news photographs gathered from the Internet to create a cohesive image with intrinsic narrative. In modifying the two elements, the entire reading of the image changes and a new story unfolds.

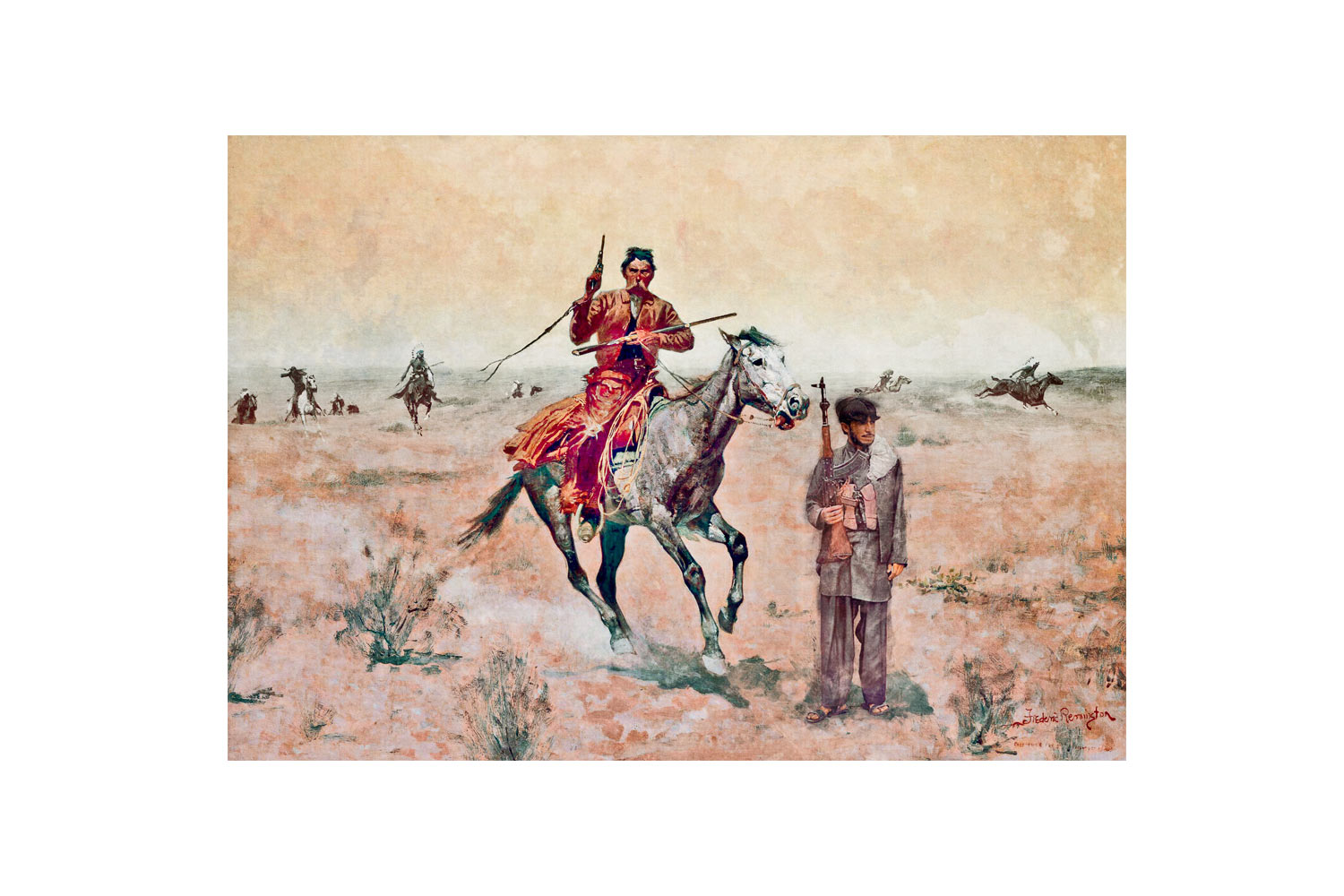

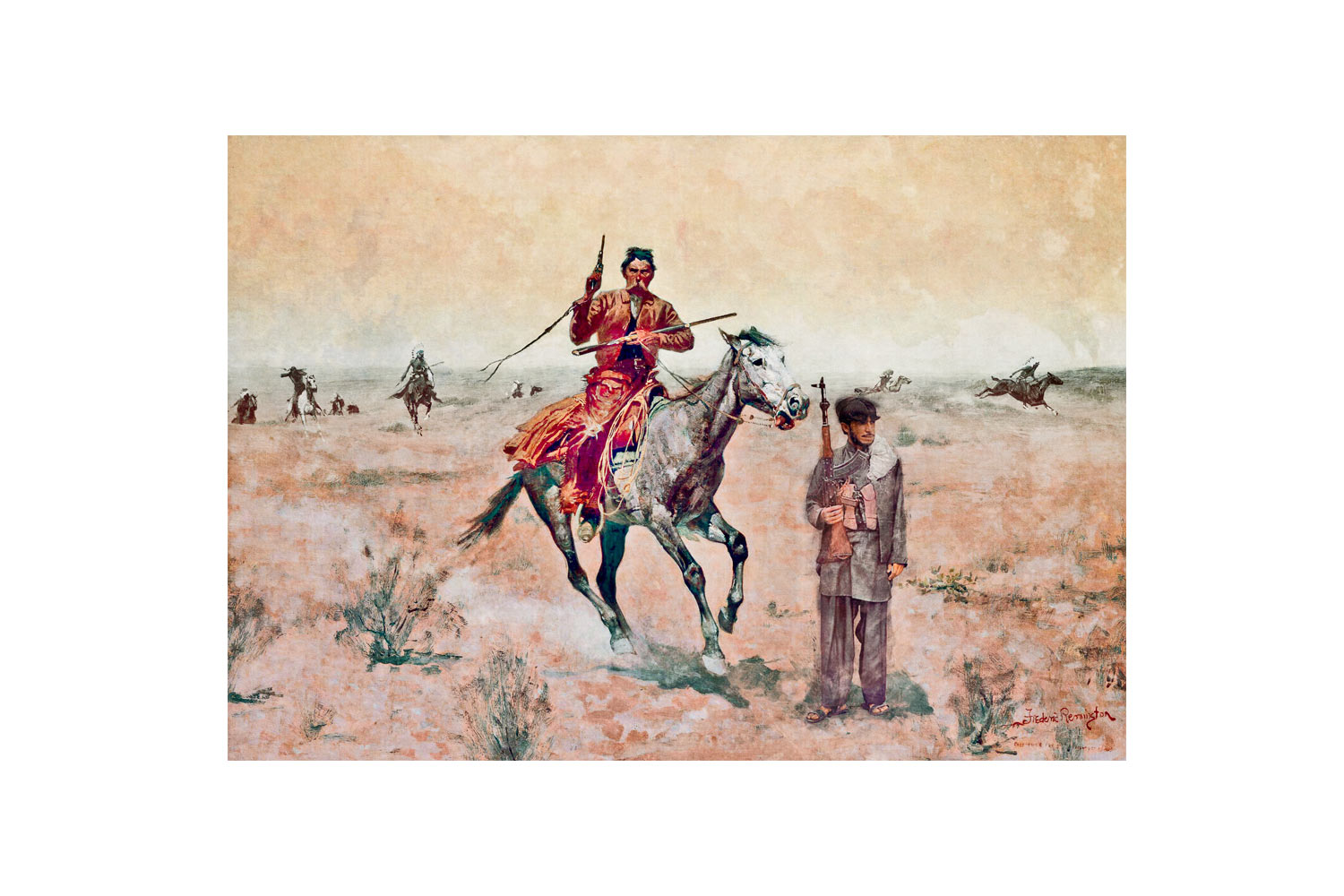

For example Frederic Remington’s Days on the Range (Hands Up, 1902) depicts a posse in pursuit of an unseen foe. In the foreground, a rider aims his gun forward as though he is about to fire. In my composition however, a young male is caught in the middle. Trying to keep his head down, he flees from the firearm and the unrelenting gaze of its beholder– will he be unharmed, or will he be shot in the crossfire? As with all other nineteen depictions in this series, this example highlights how the medium of photography plays a central role. Using photojournalistic images and representations of the chosen mythologizing paintings, I have extensively reworked these pictures to fashion a new telling that looks seemingly accurate, but involves an impossible and/or highly fabricated narrative. With Wetiko – Cowboys and Indigenes, I therefore draw from visual influences to at once exaggerate the manipulative nature of photography, and to directly trace and challenge the history of fabrication.

However, such work cannot be created until we become liberated from the original form. In order to deconstruct it, we have to divorce ourselves from the Wild West and Orientalist images as well as the photojournalistic images– and their perceived truthfulness – in order to visualize and convey something new.

For this separation to happen, there is a period of loss of faith, which many of us may struggle to contend with. We often become trapped in the preconceptions of what we have been shown and told to believe. But what we have to remember is that these imageries are based on the fictions and fantasies of their creator: They are visual mythologies that we choose to regard as truth.

It was Wild West paintings by artist-correspondents akin to those incorporated in Wetiko – Cowboys and Indigenes, which seduced the Irish-American film director John Ford to imagine his influential Western films. Not only did Ford manage to popularise a hackneyed genre in Hollywood cinema, but his Westerns became imbedded in the American psyche, influencing film and popular culture with his Wild West stereotypes. These self-created Wild West imageries by filmmakers like Ford, and the artist-correspondents employed in this series, all highlight the cowboys and the West as the prevailing, up-keepers of morality.

The East and its people on the other hand are shown as the weaker group with little or no movement. Reflectively, it is mythologizing depictions like these that have too influenced long-lasting perceptions of us and of others, encouraging essentialist beliefs that remain dominant today. The Arab people, for example, are trapped in Orientalist portrayals of the East. Orientalist painting was particularly popular in 19th Century academic art; at once inspiring European literature on the subject, and leading to the growth of a somewhat patronising Western attitude of the Middle East and other Eastern societies as inferior and static. Accordingly, Eastern populations have learned to see themselves through the eyes of the West. Perhaps this cultural brainwashing is part of the reason why the pan ethnic group puts up little or no resistance to the West’s intrusions and acts of authority.

However these artistic renderings that have inspired the thought of generations have little to do with the truth of the lives of the people they represent. Moreover, they show prevalent views of society and/or the creator, rather than the reality of the other being depicted. Still, this ideology has been built layer by layer over time. These ideas have moved from fantasies of the self to paintings, and then from paintings to film, to create a popular culture, which is today confirmed by photojournalism – our so-called beacon of objective reality. The portrayal of the East appears to be an apposite vessel through which the impressions and ambitions of the West could be drawn and enforced. In modern times, as addressed at the beginning of this text, the same thing happens. Revolutions that carry Western ideals of democracy for example happen there, or when they don’t, they are simply fabricated to compose a reality more pertinent to the purposes of the visiting camera lens.

With a long history of influential visual imageries based on imagination rather than the reality of the situations they are representing having such an impact on contemporaneous culture, it is no wonder why today’s published image is so often used as a tool for public consumption. When it comes to photojournalism however, one is forced to question the rhetoric’s of its authenticity. Our modern-day interpretation of non-staged scenes as an appropriate foothold is too naïve. There are photojournalists today who still espouse to use image enhancing or photo editing software, like Photoshop, for greater effect. Albeit any reasoning, this does not adhere to a ‘greater truth’. If a photojournalist brings back images of a situation and the photo-editor removes those that appear non-germane to the caption of the article, is this an accurate portrayal? Not only does this manipulate our response to the situation, but also it transcends the ethics of photojournalism by evading its responsibility to document and communicate the whole reality of what is being portrayed.

As this project shows, once we are able to recognize the influences of the media, history, and myths, and we start to question or deconstruct their implications, a new form of seeing transpires. By superimposing new visual elements into famous paintings of mythologized settings and ergo reworking their impression or meaning by creating new visual narratives, Wetiko – Cowboys and Indigenes accentuates the ability of the image to modify opinion and belief.

It also reflects this process of self-liberation. Once we distance ourselves from something (in this case the truthfulness of the Wild West and Orientalist depictions), we can start to play with its language. For example, I combined Remington’s Through the Smoke Sprang the Daring Soldier (1897) with an image of Marilyn Monroe, who appears to be singing to a group of 19th-century soldiers in the midst of battle. The original story reflects a skirmish between cavalry troops and a band of Northern Cheyenne in Nebraska. It focuses on the bravery of the courageous sergeant who leaps out of his trench to face their enemy. In my composition, a notably glamorous woman is the focus of attention. This image of Marilyn was taken in Korea in 1954, when she sang to the troops to charm them and take their minds off their impending potential death. I found this idea, and her seduction, similar to the story that Islamists tell their jihadits and suicide bombers – that when they die they will find a decimal odd array of virgins waiting for them in Heaven. In this work I therefore draw similarities between human beings, highlighting that our differences are in fact more subtle than we realise. The novelist and poet (or you could say the fabulist) of the British Empire, Rudyard Kipling, phrased it neatly in the final verse of his poem:

But there is neither East nor West, nor Border, nor Breed, nor Birth, When two strong men stand face to face, tho’ they come from the ends of the earth!

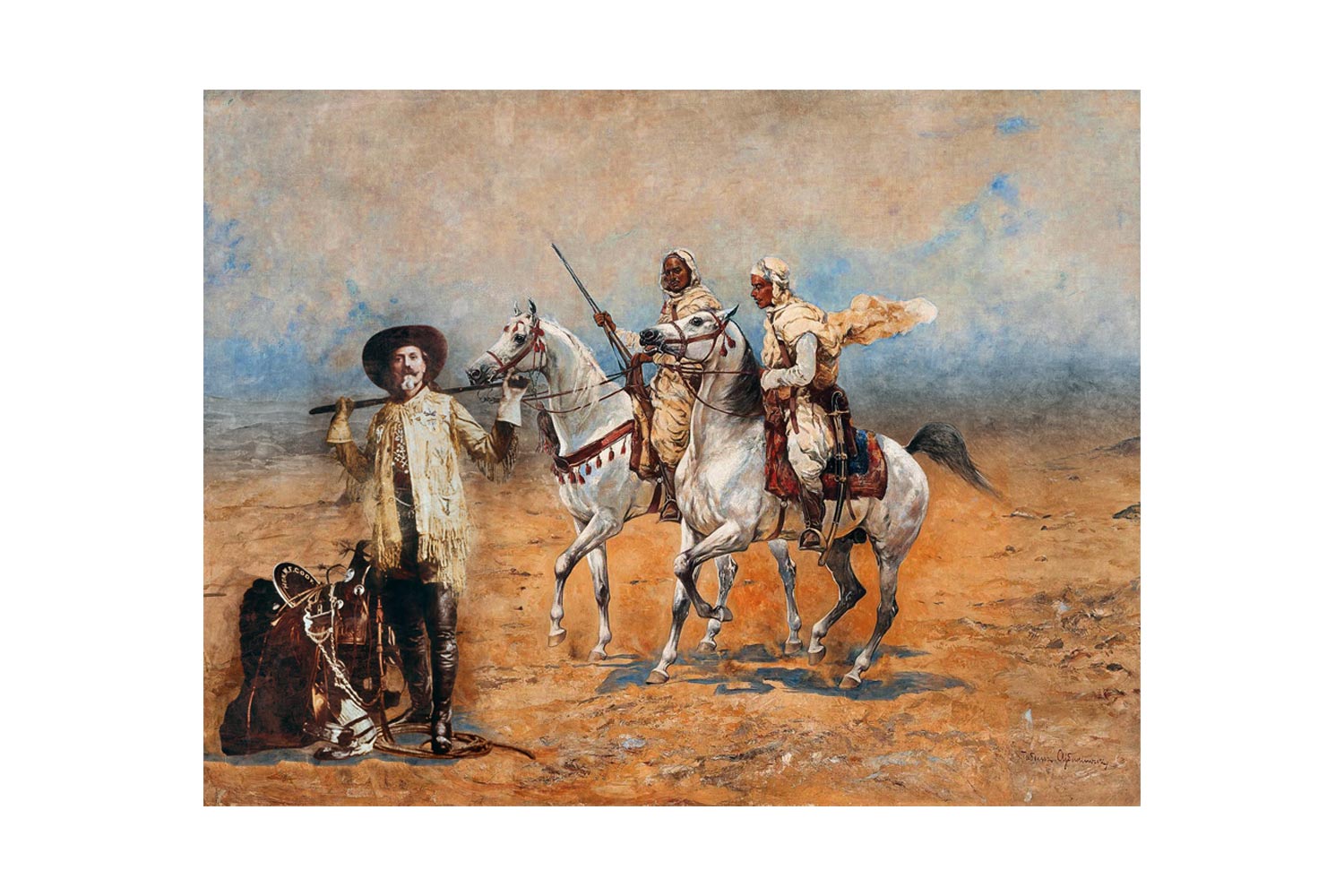

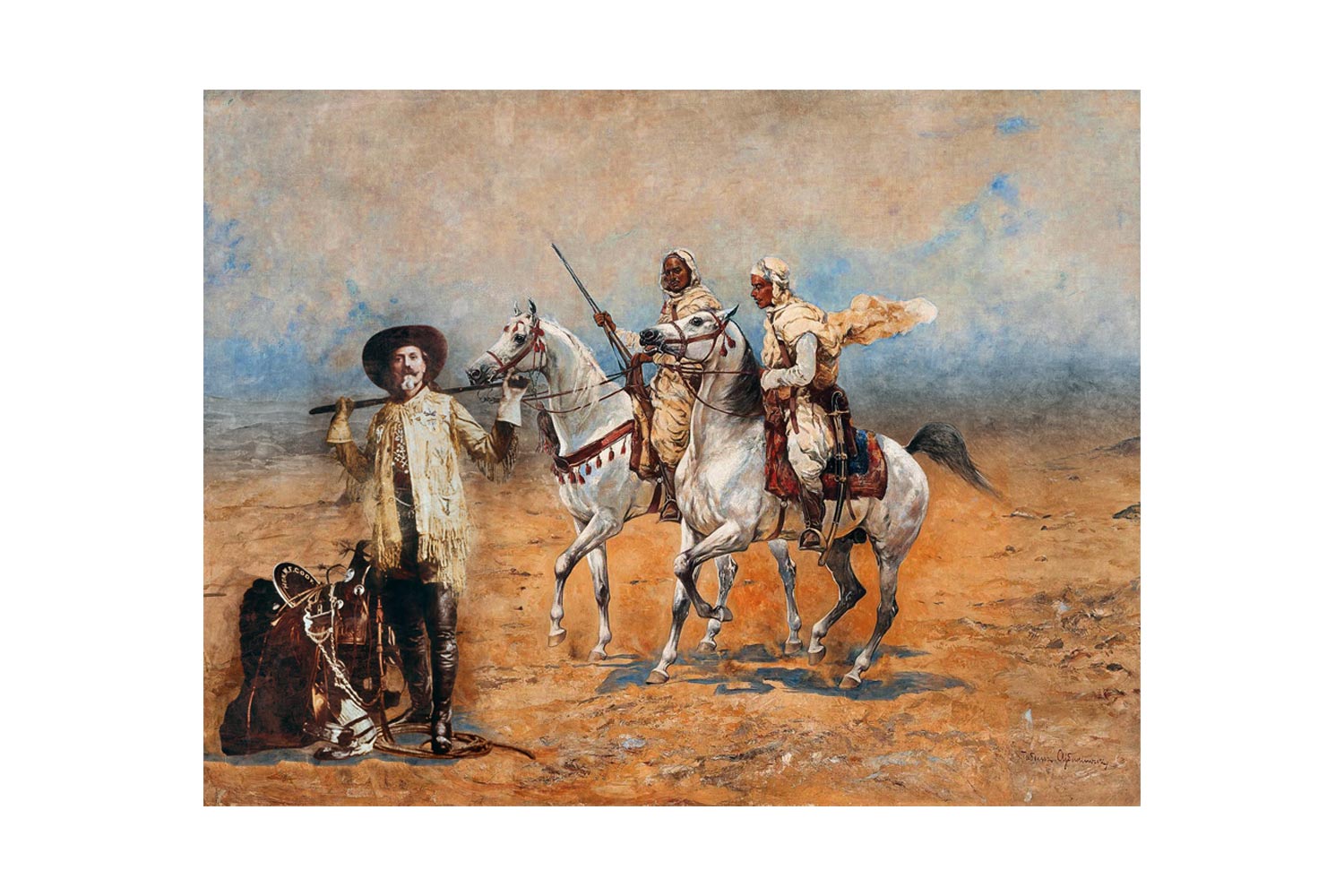

Horseman in the Desert by Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz and Buffalo Bill by Adolf Spor (1900/1958)

61.5 x 80 cm

Aat posuere sem accumsan nec. Sed non arcu non sem commodo ultricies. Sed non nisi viverra

Nulla blandit

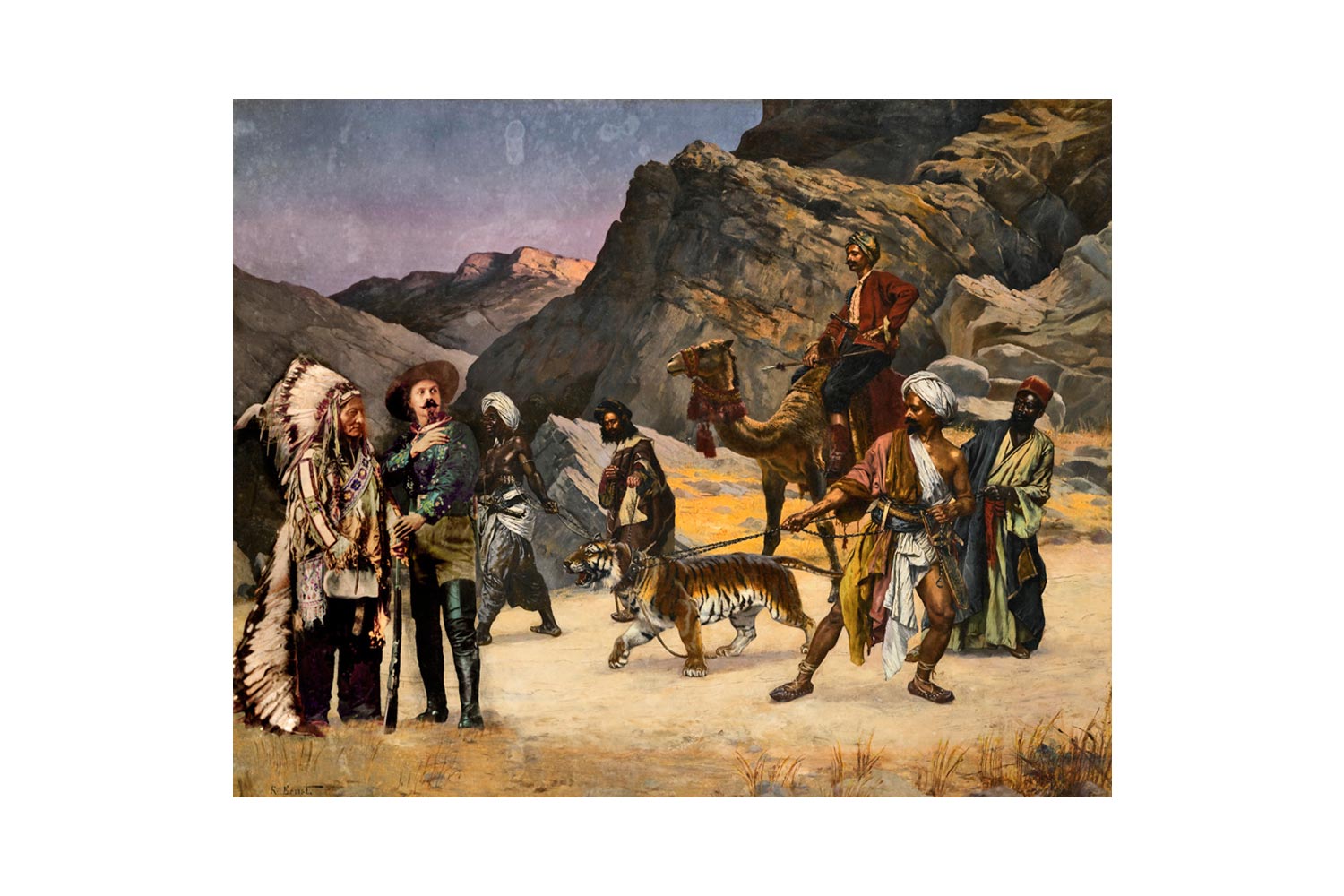

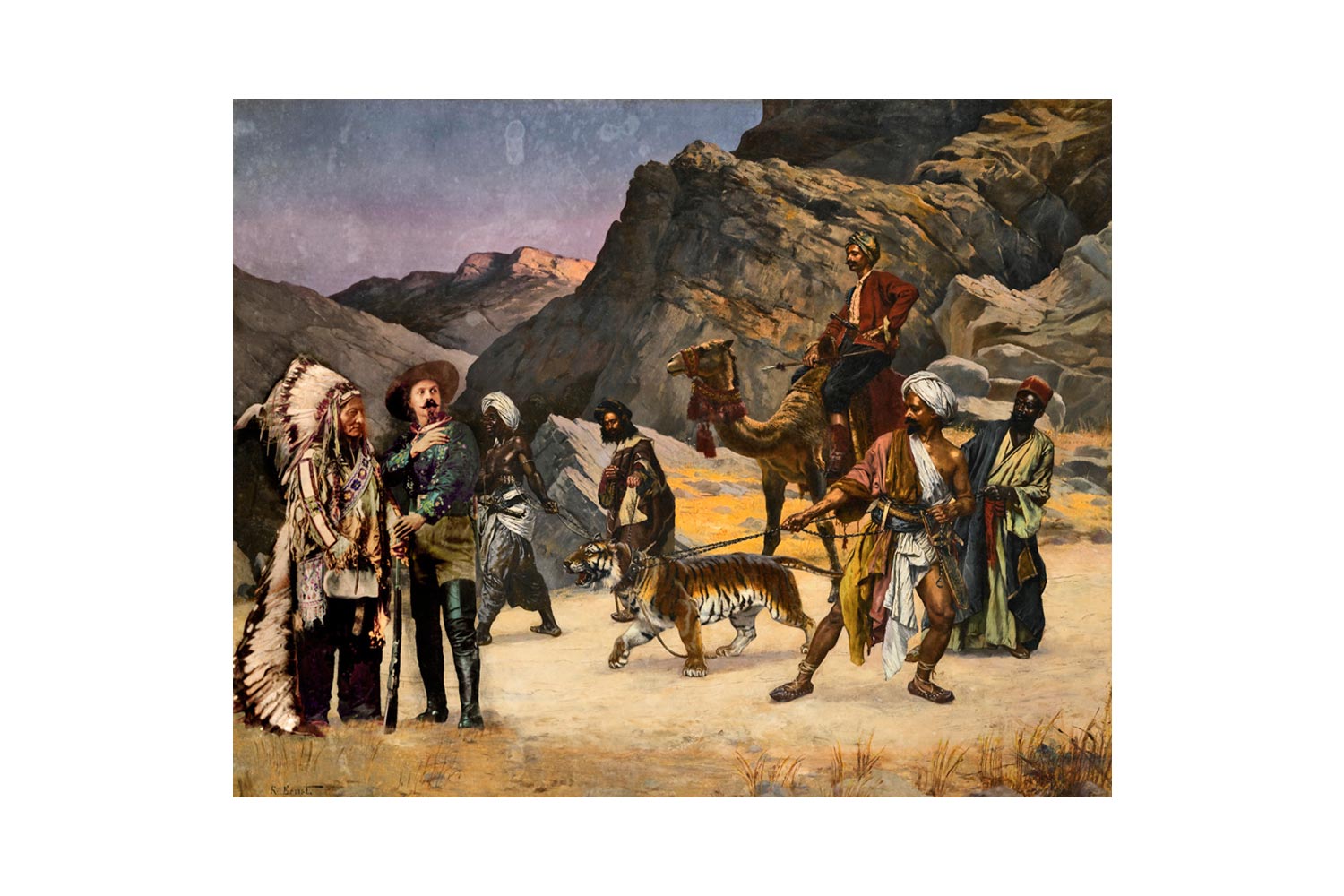

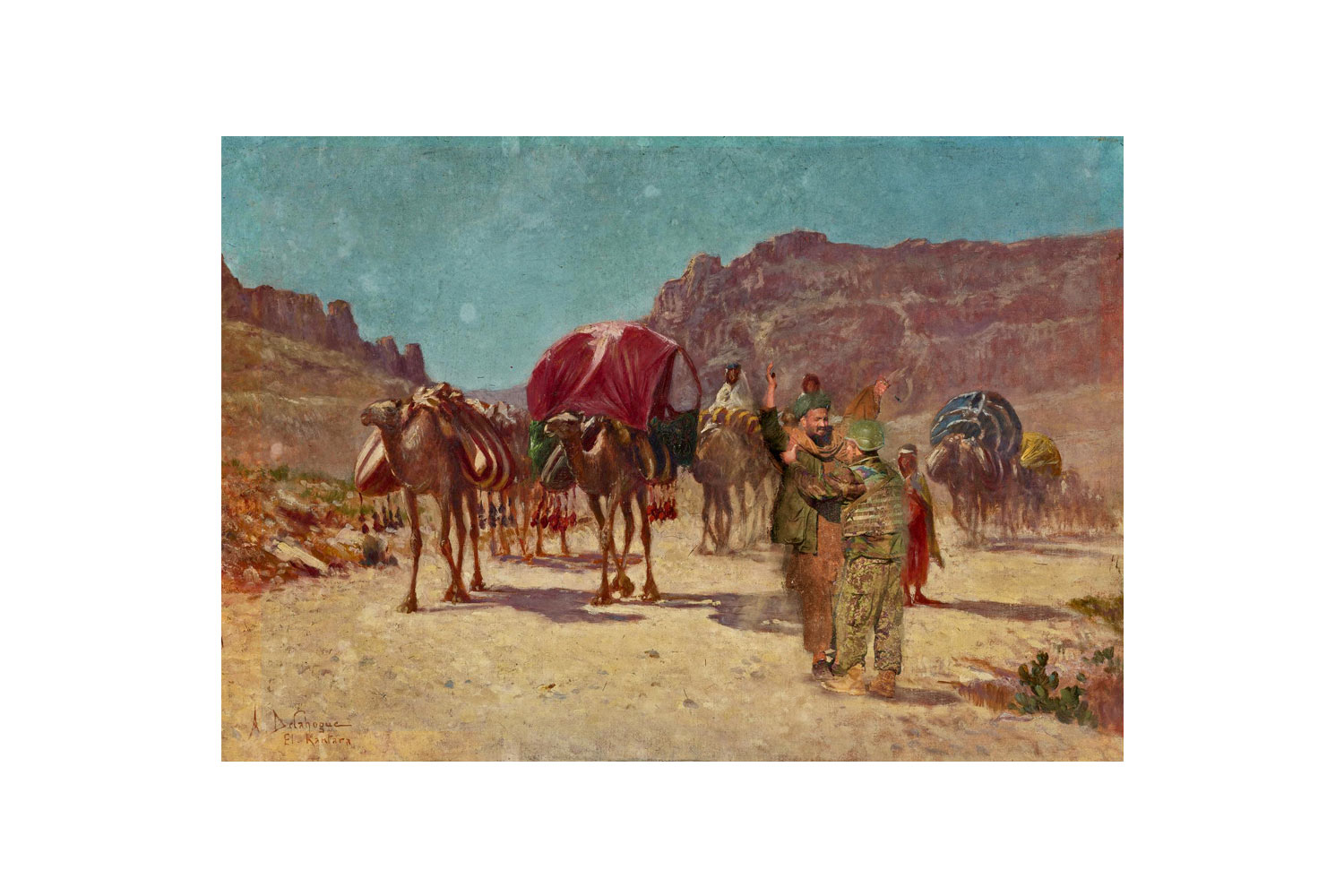

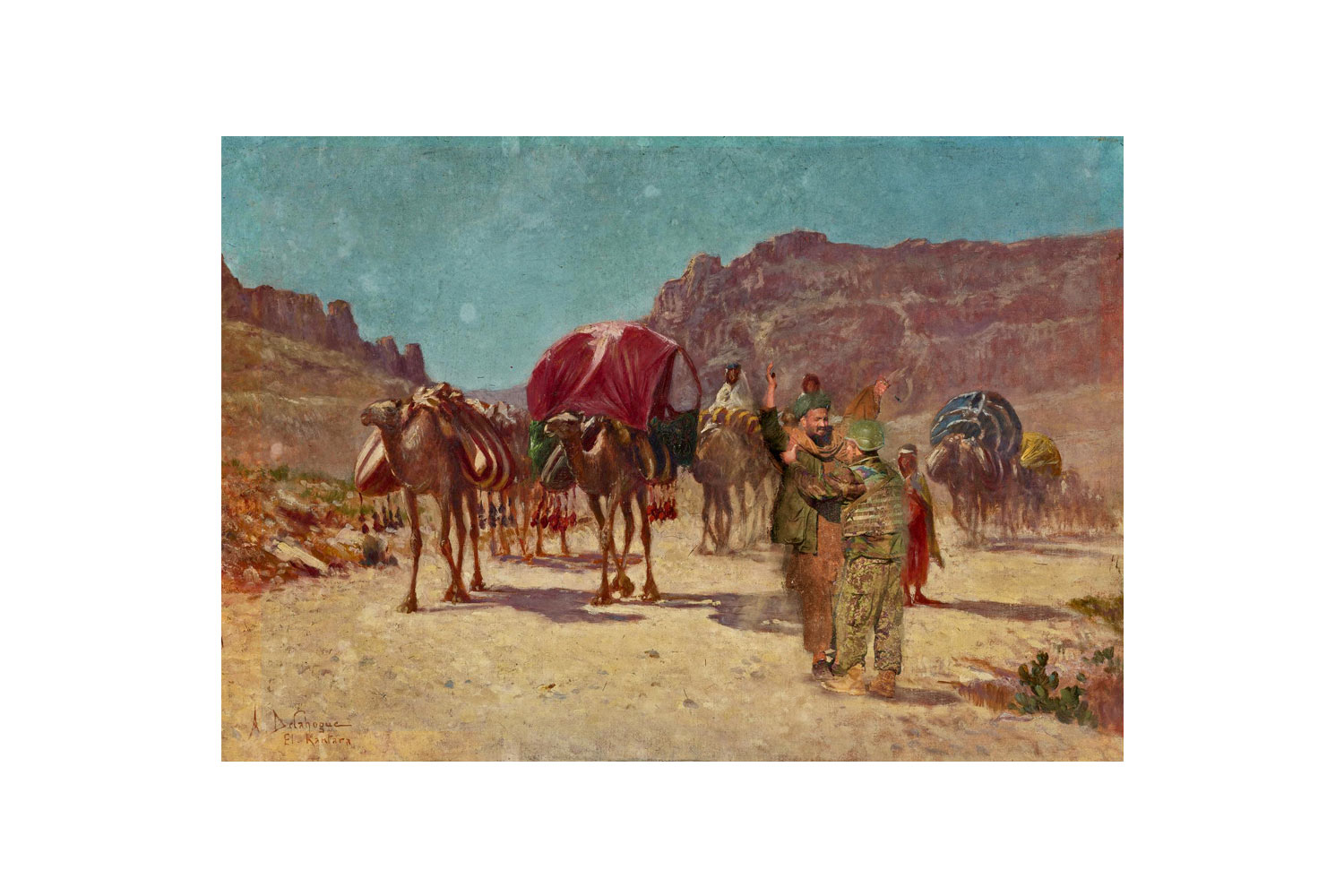

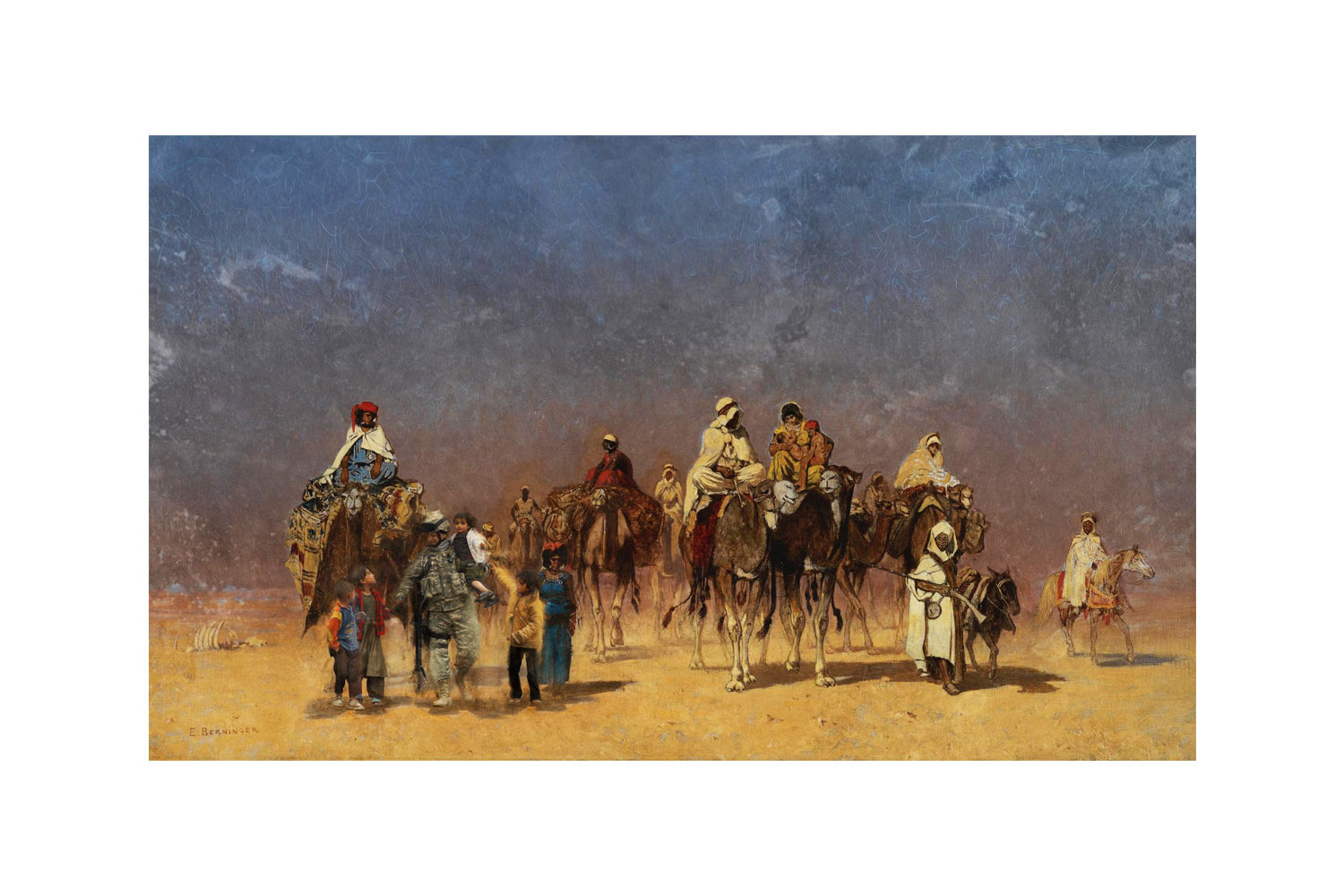

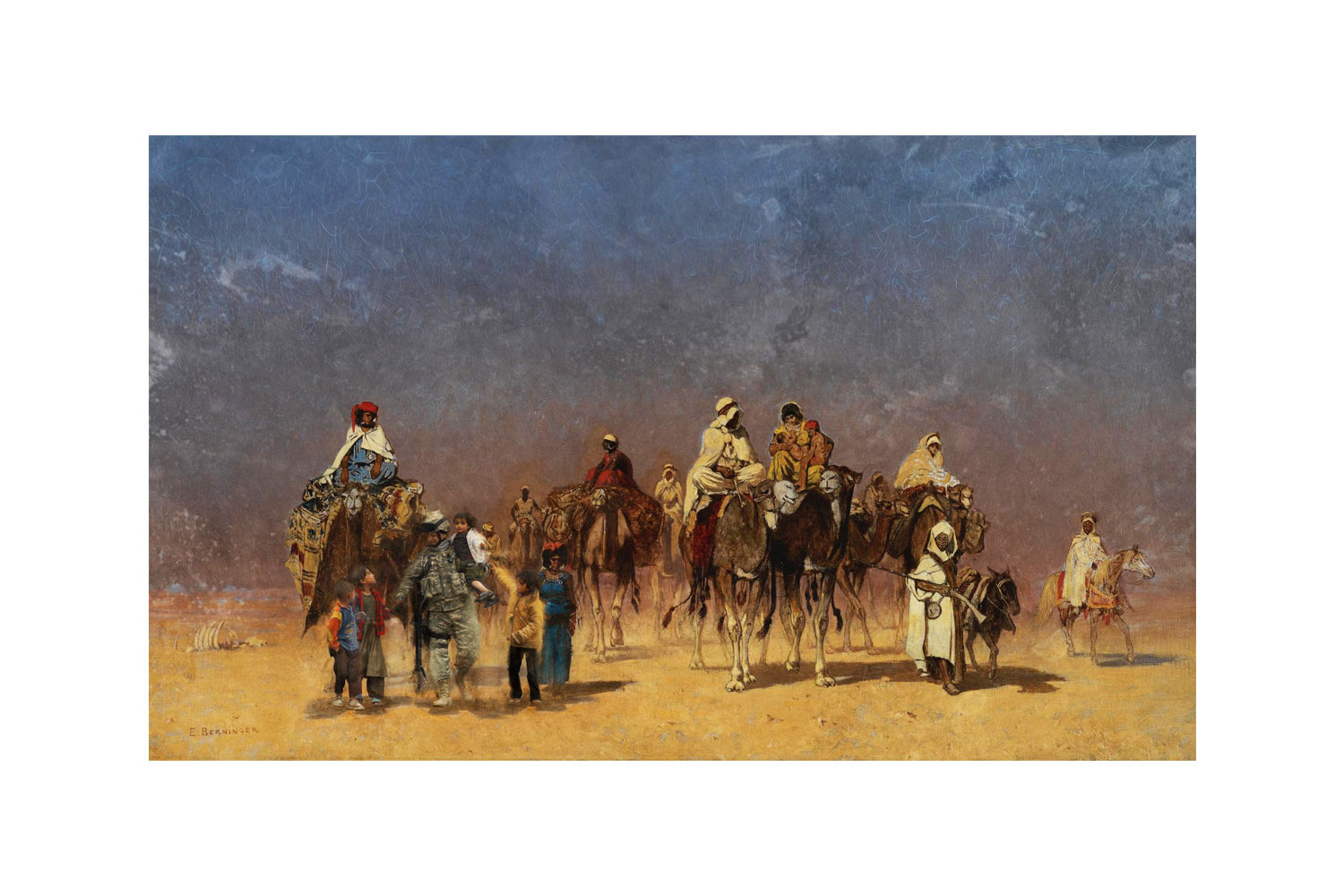

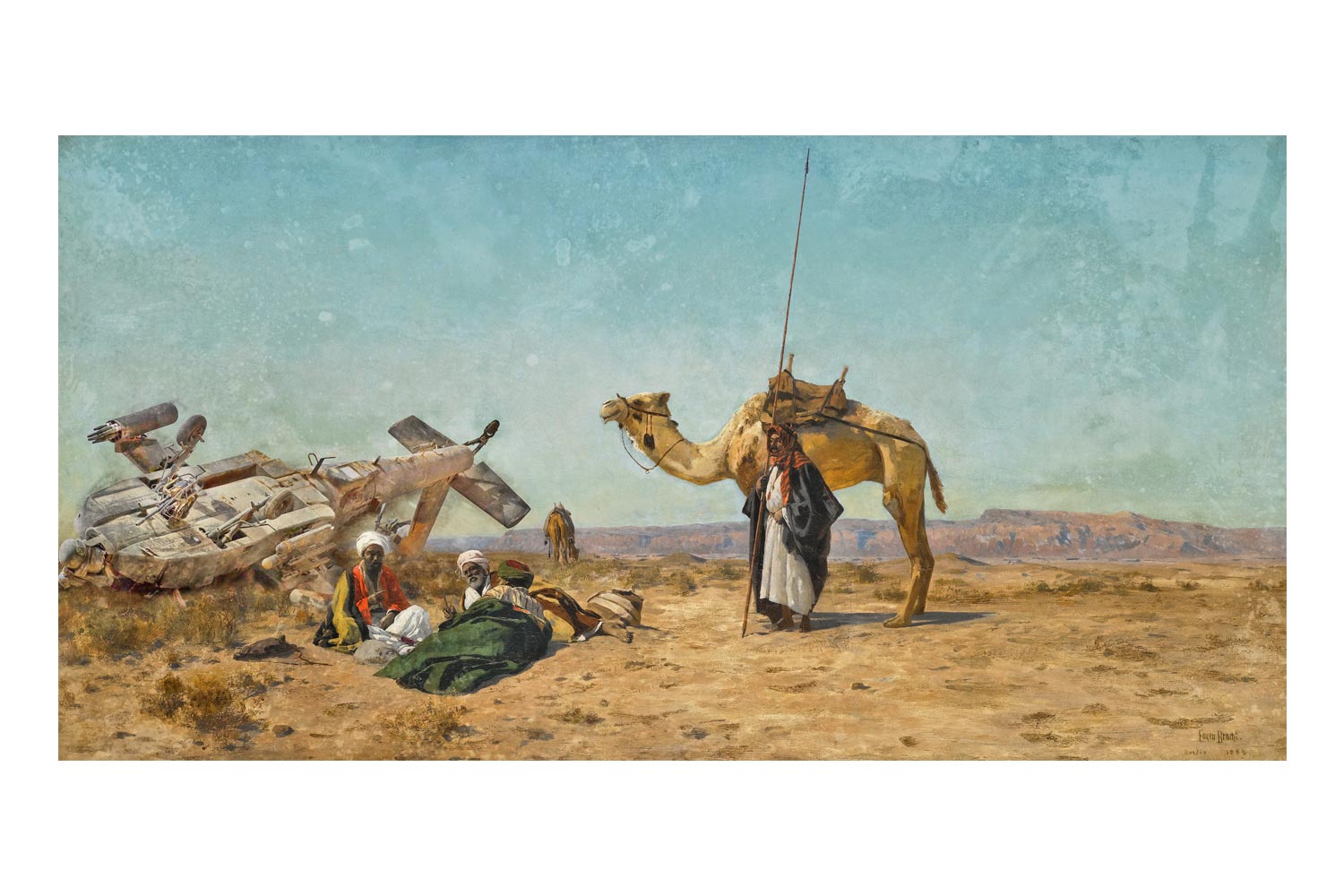

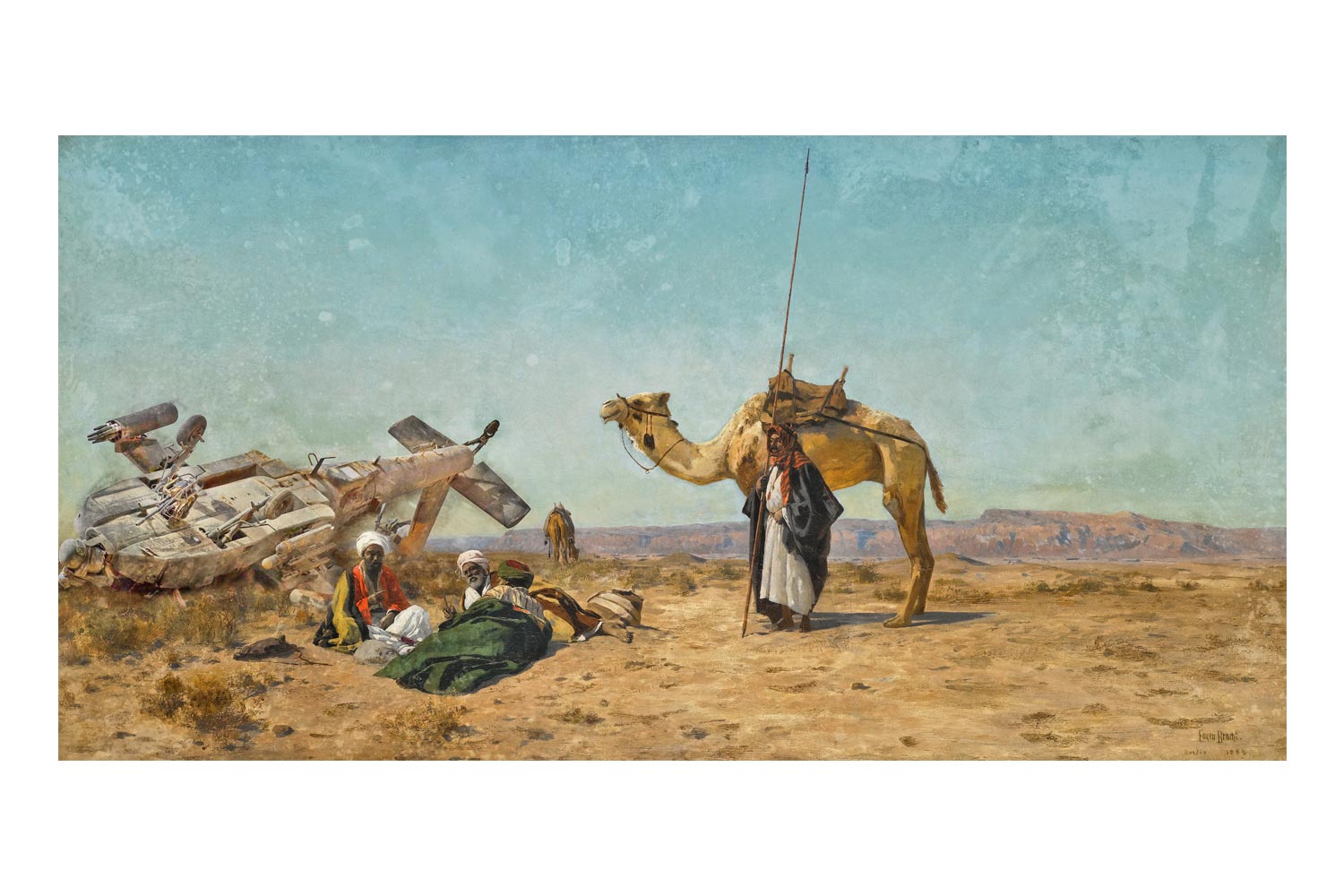

An Algerian Caravan in El Kantara by Alexis Auguste Delahogue (Late 1800s)

56 x 80 cm

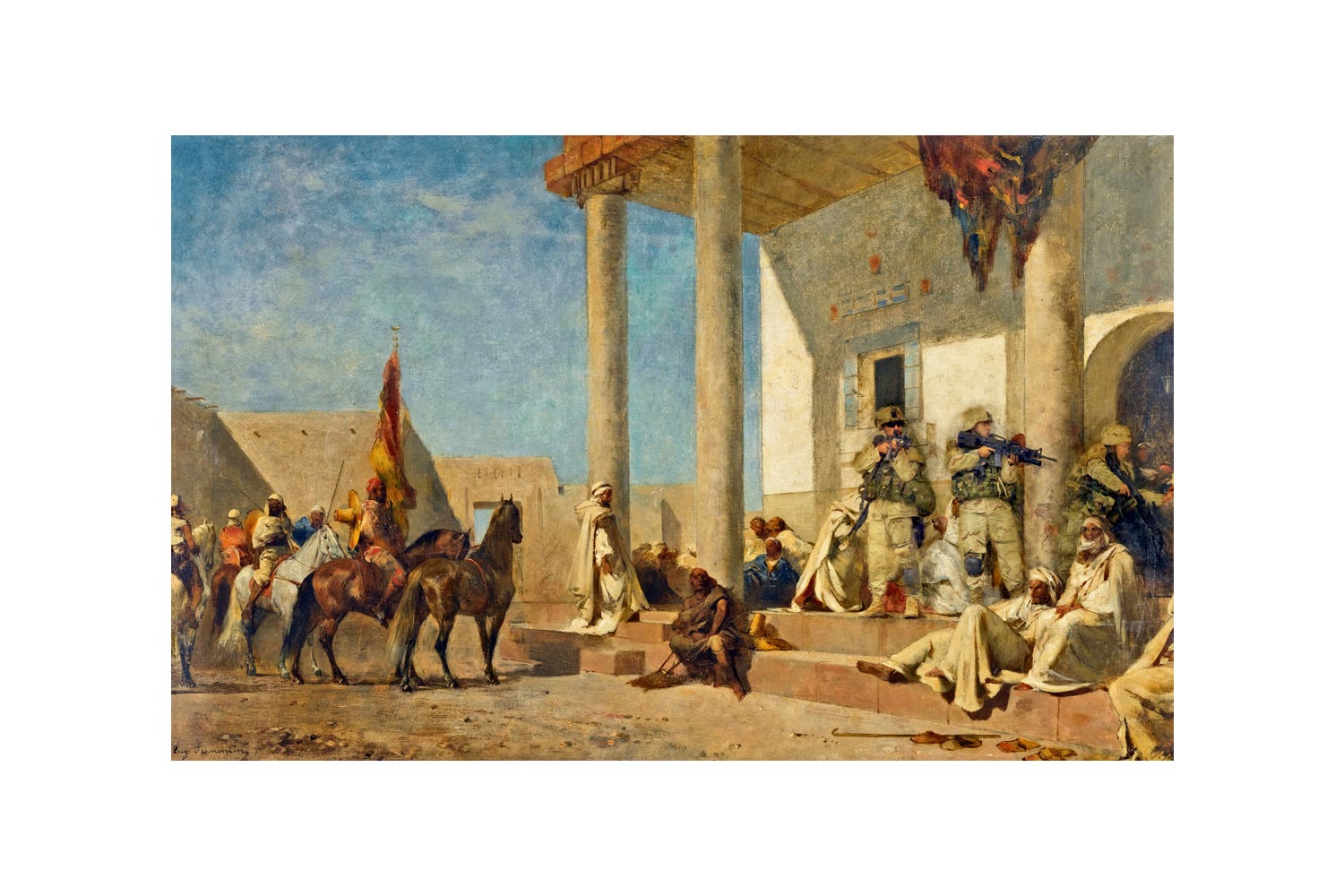

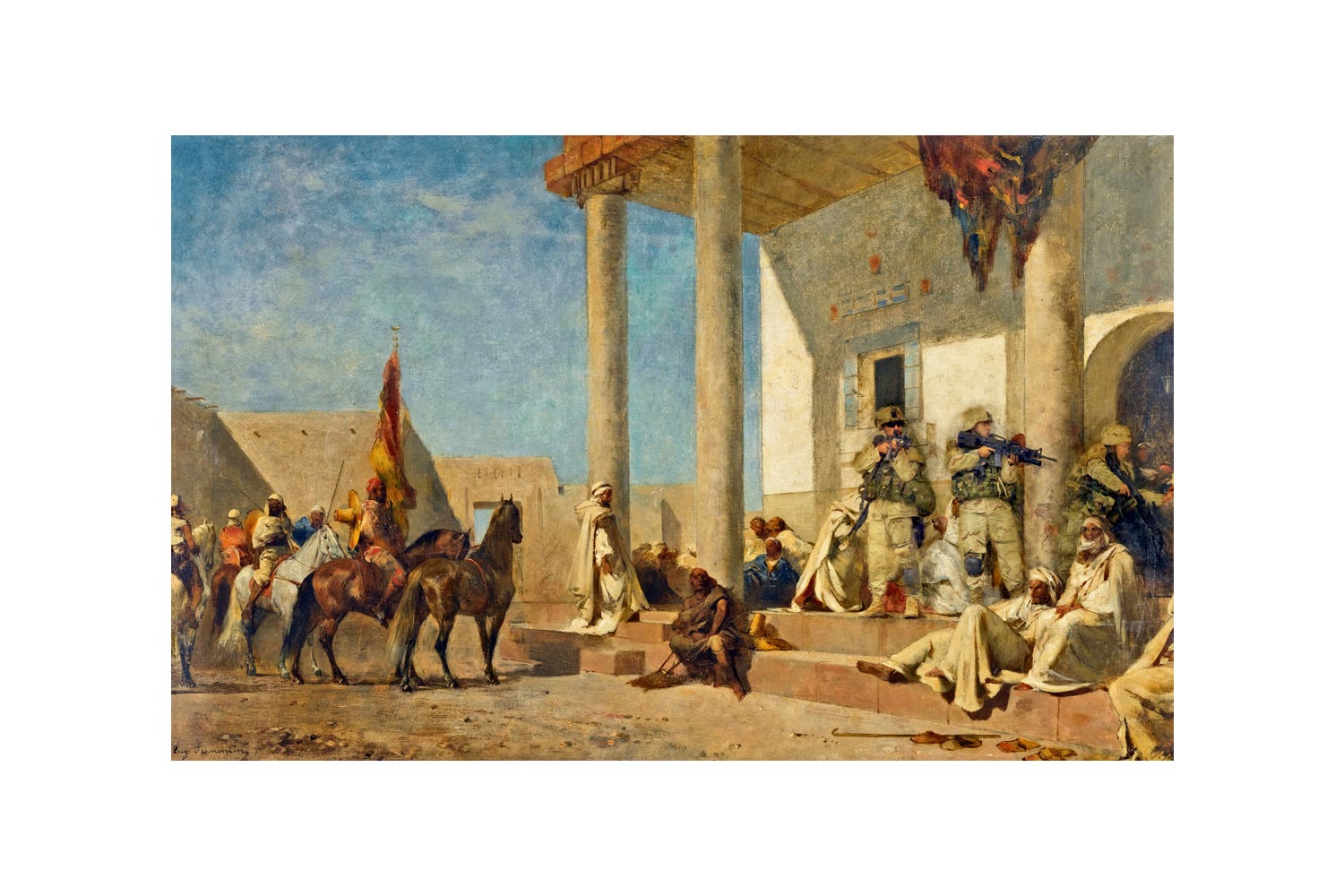

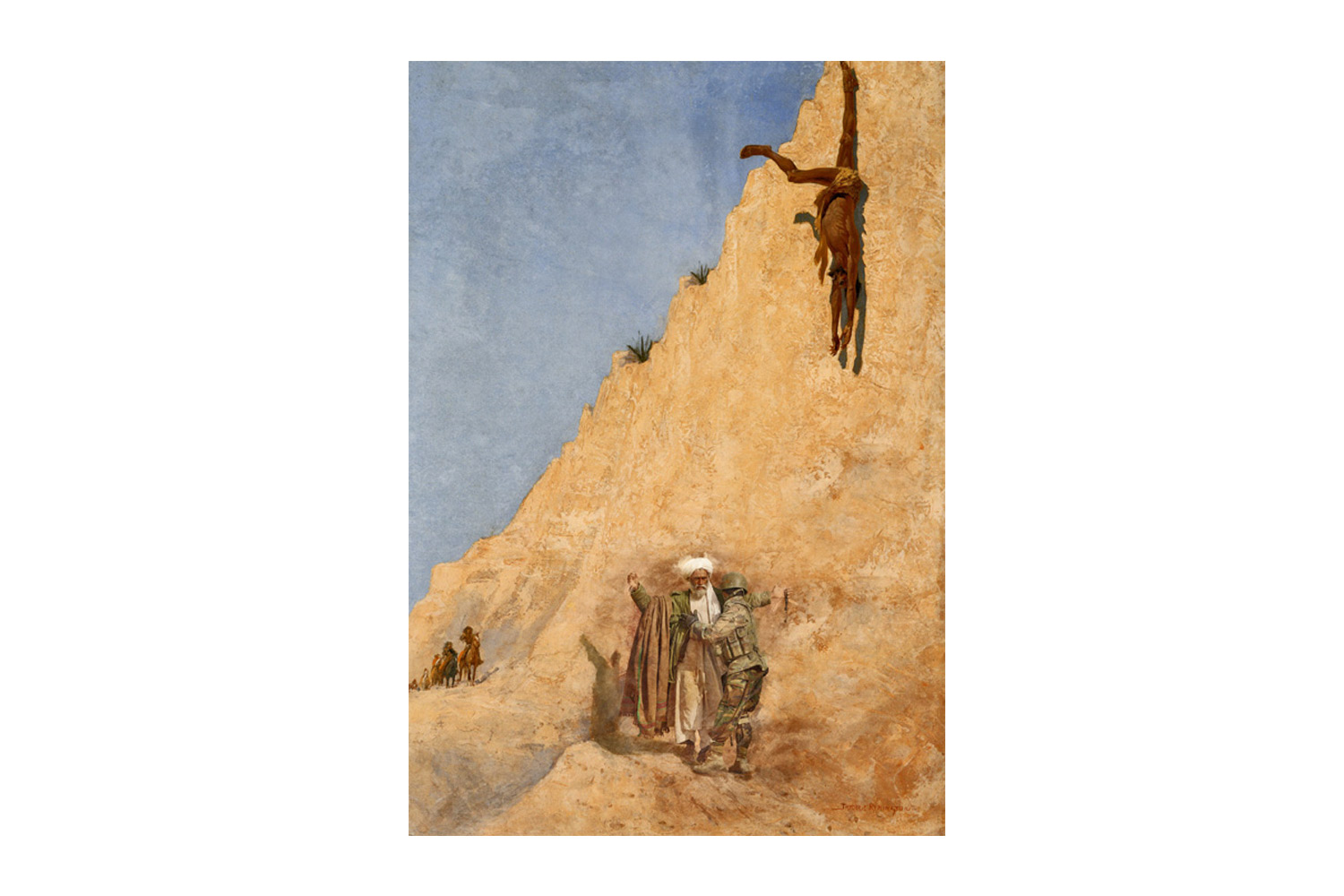

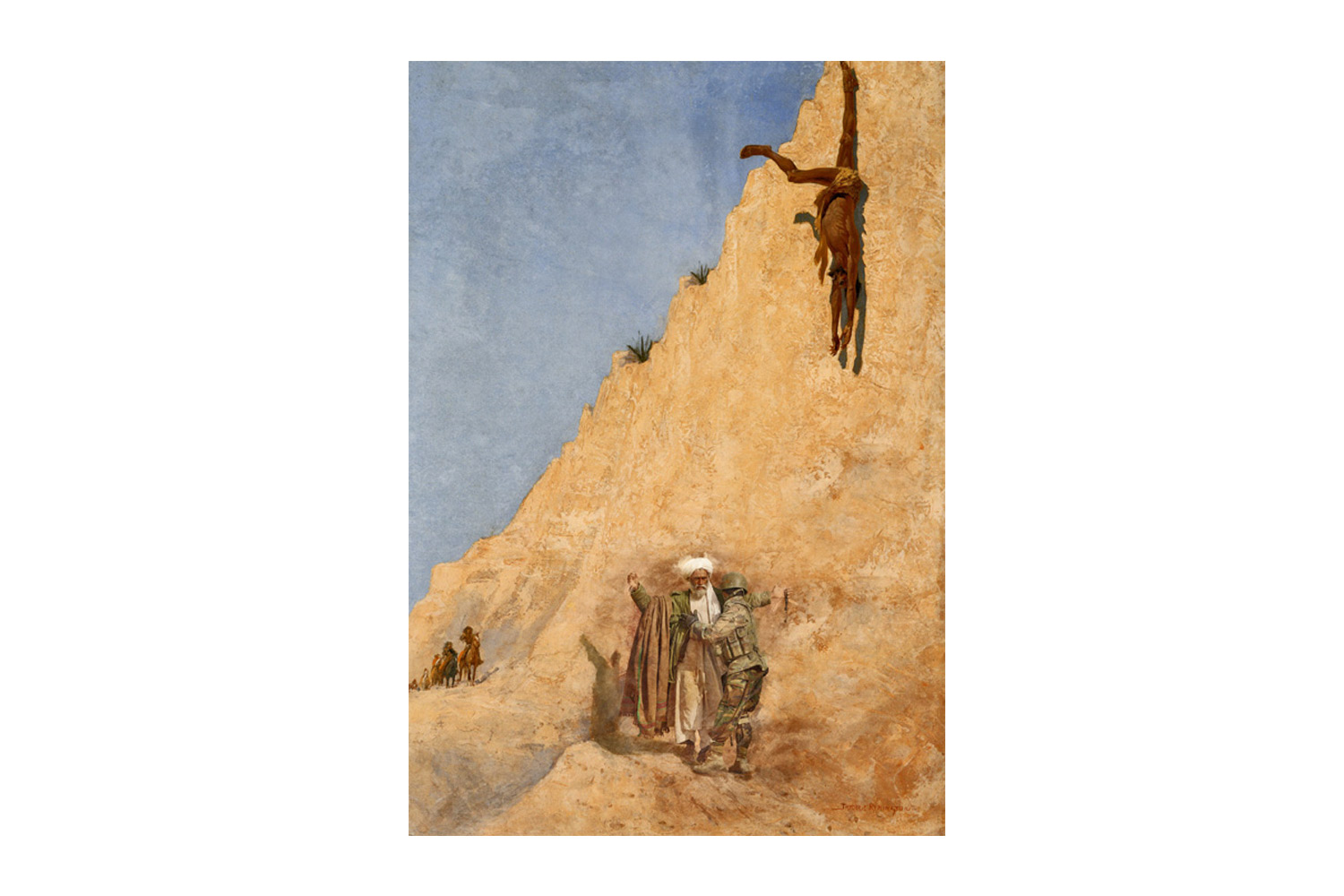

Audience Chez un Khalifat by Eugene Fromentin (1859)

63 x 80 cm

Aat posuere sem accumsan nec. Sed non arcu non sem commodo ultricies. Sed non nisi viverra

Nulla blandit

Aat posuere sem accumsan nec. Sed non arcu non sem commodo ultricies. Sed non nisi viverra

Nulla blandit

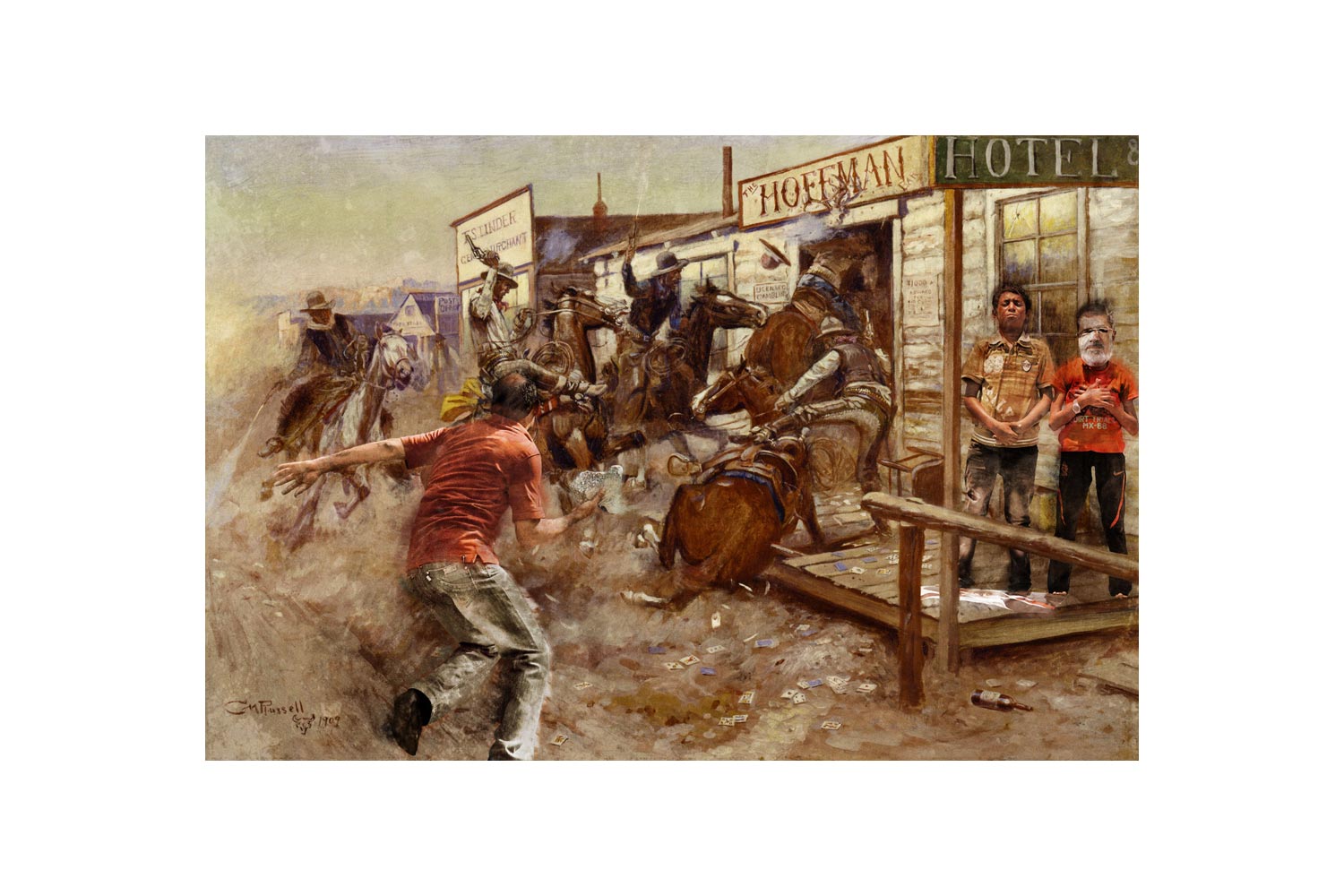

Days on the Range (Hands Up!) by Frederic Russell

80 cm x 54

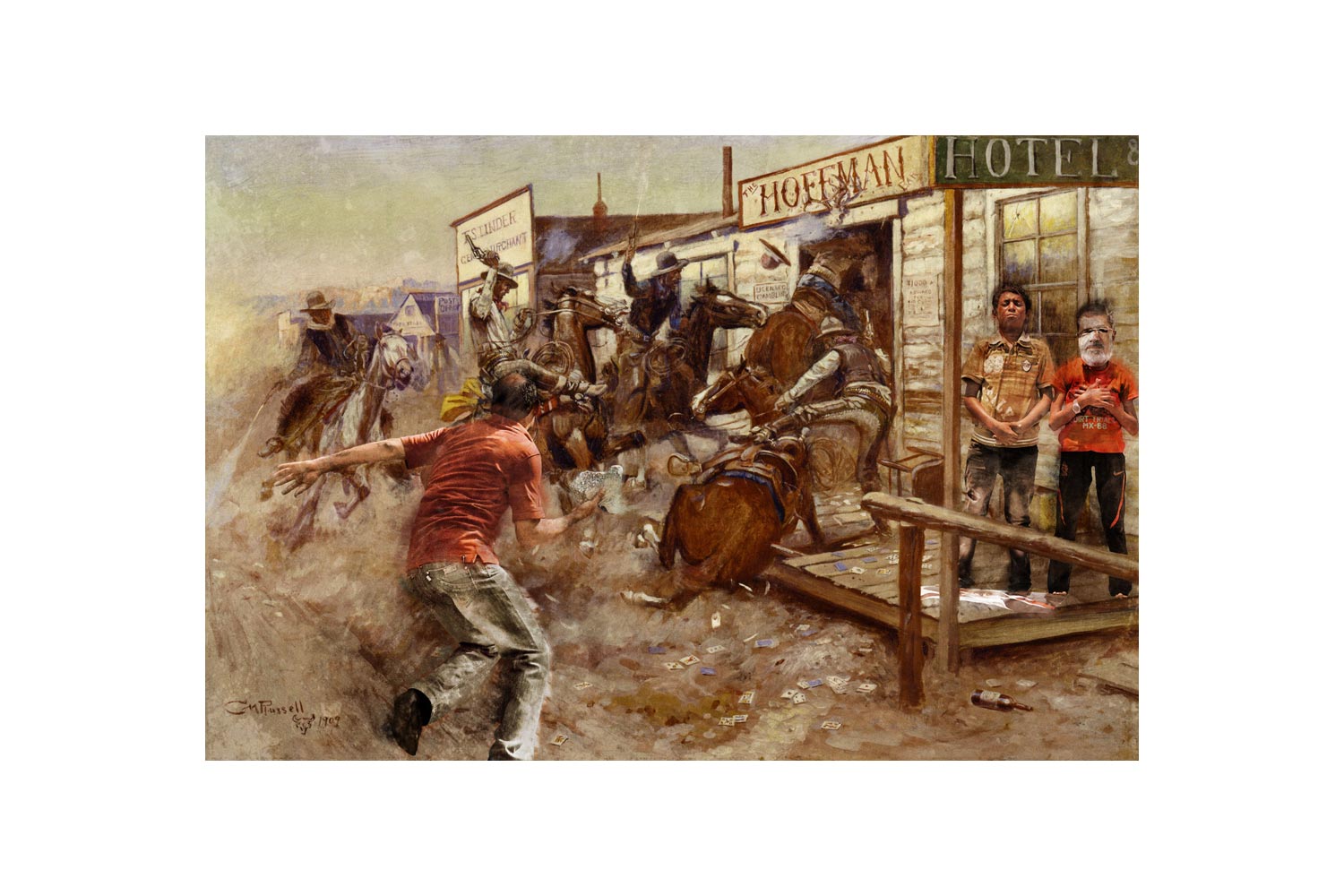

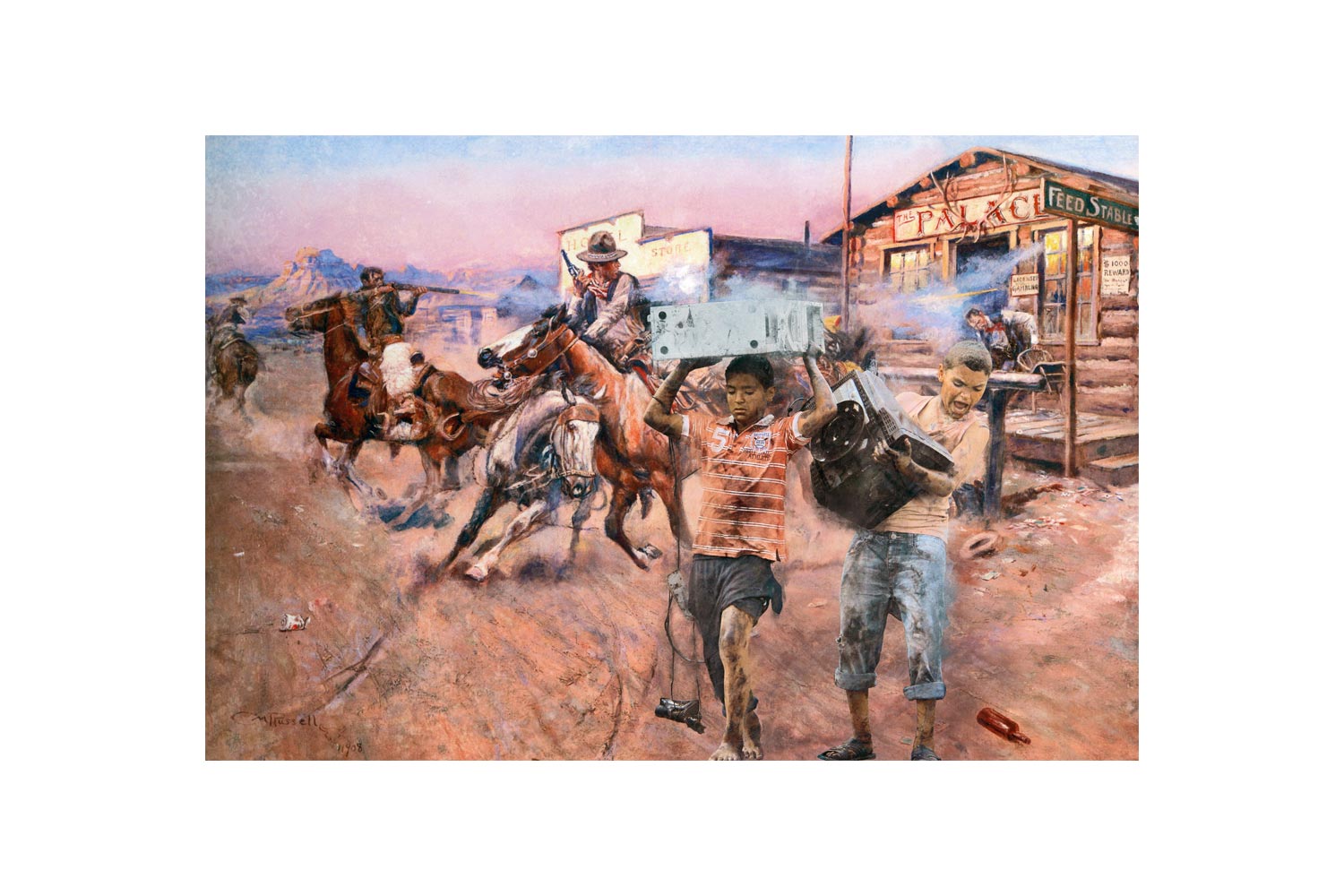

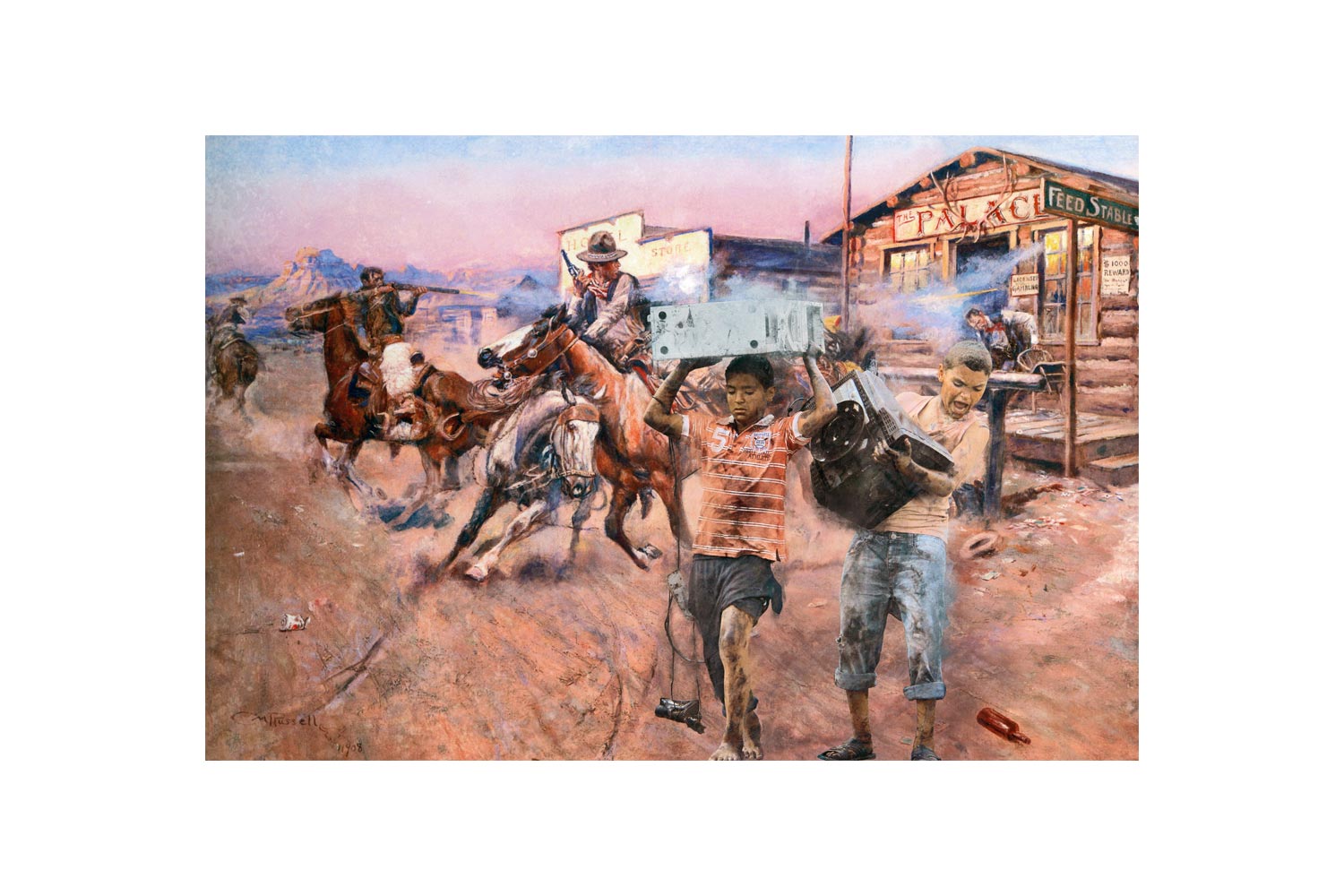

In Without Knocking by Charles Marion Russell

54.5 x 80cm

Aat posuere sem accumsan nec. Sed non arcu non sem commodo ultricies. Sed non nisi viverra

Nulla blandit

At Rest in the Syrian Desert by Eugen Felix Prosper Bracht (1883)

41 x 80cm

Roping a Rustler by Charles Marion Russell (1903)

55 x 80cm

Smoke of a .45 by Charles Marion Russell

54 x 80 cm

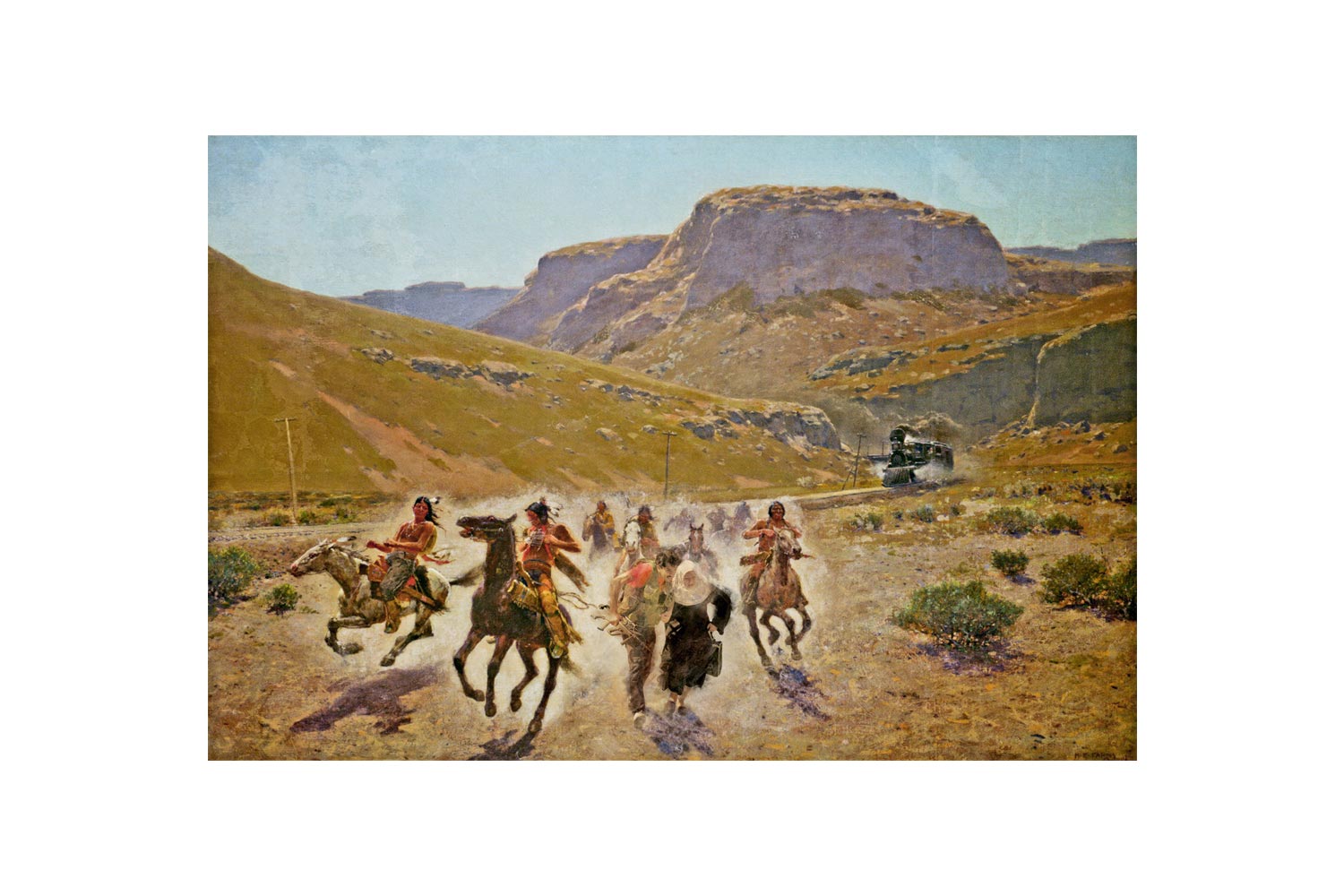

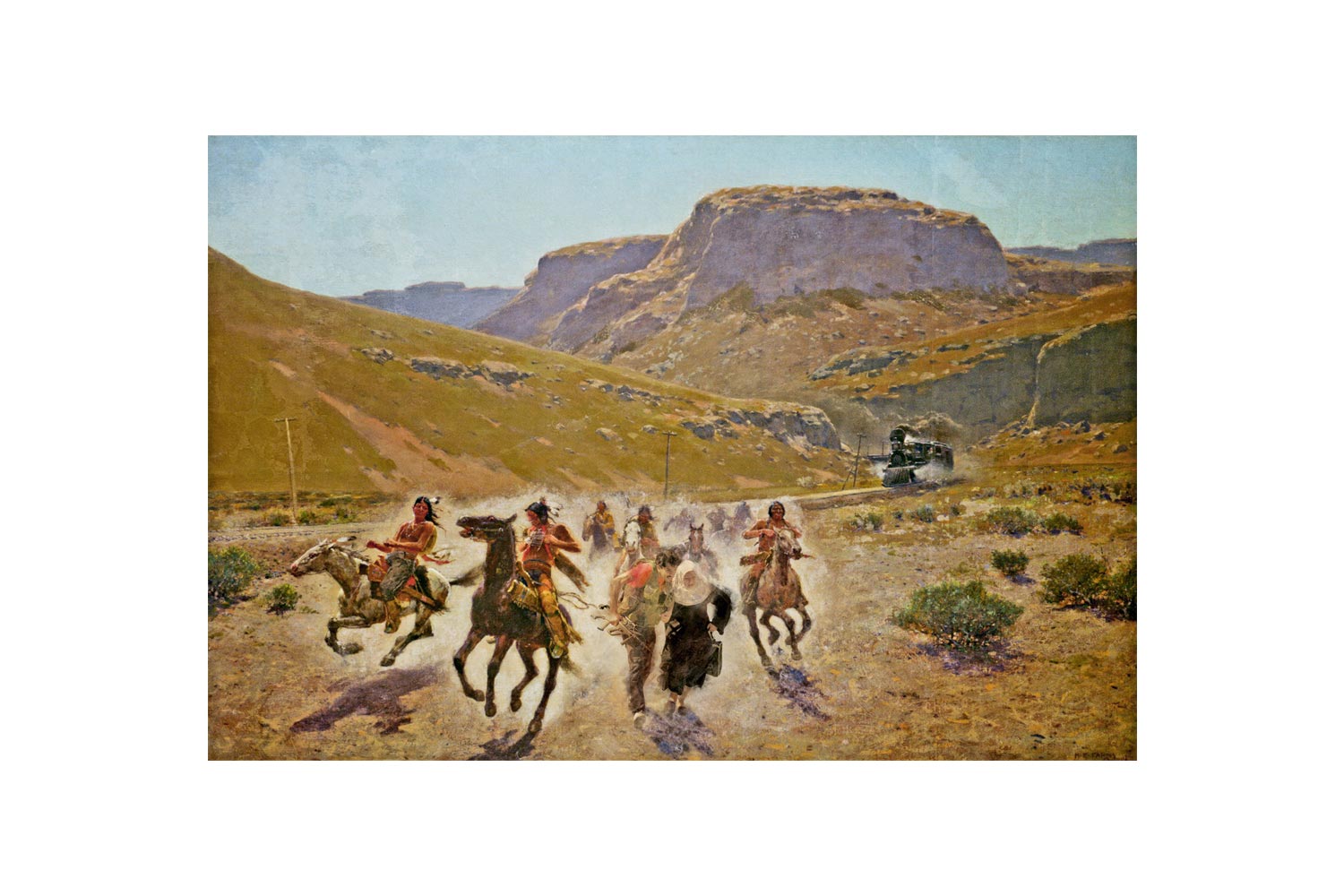

The Coming of the Fire Horse

80 x 53 CM

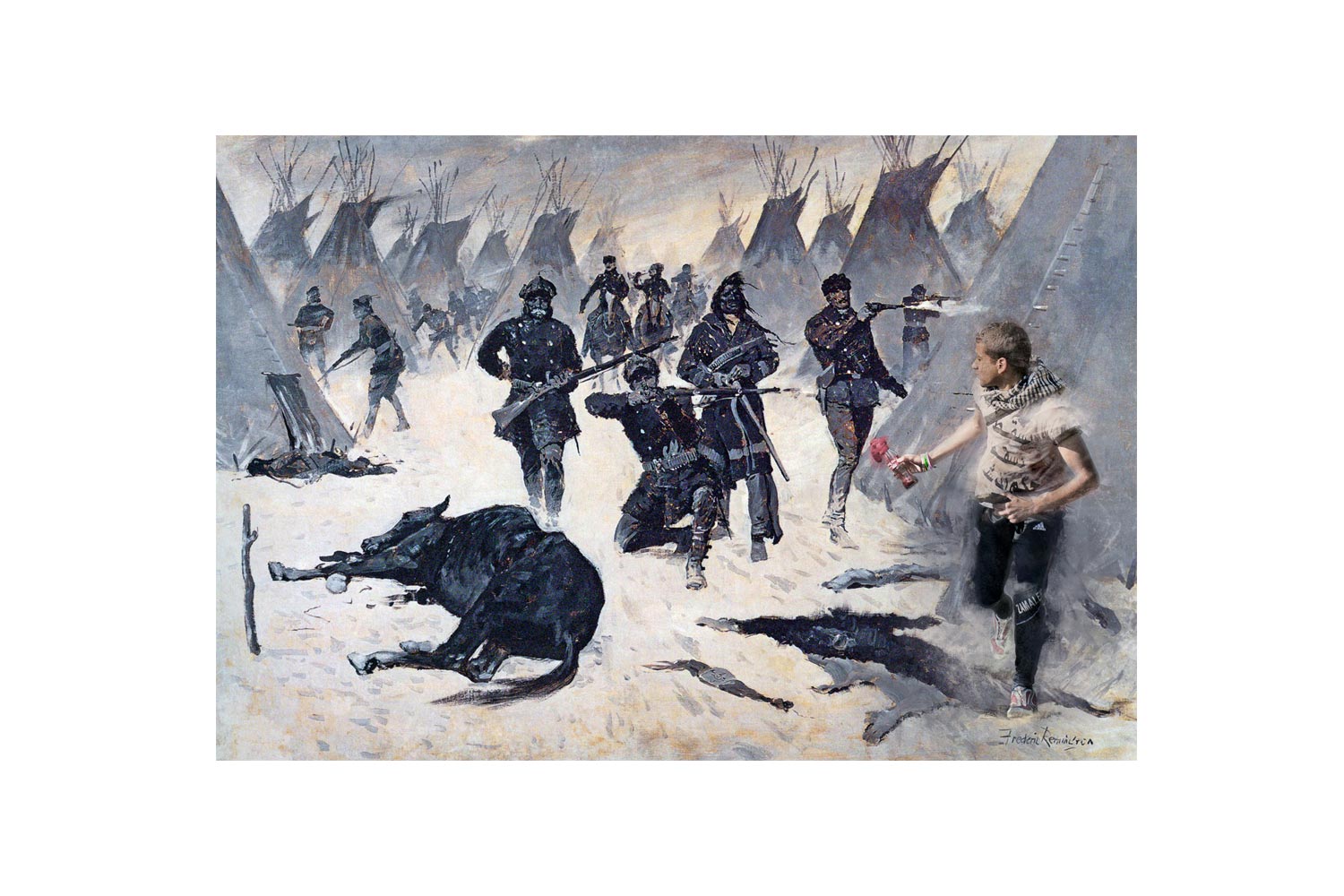

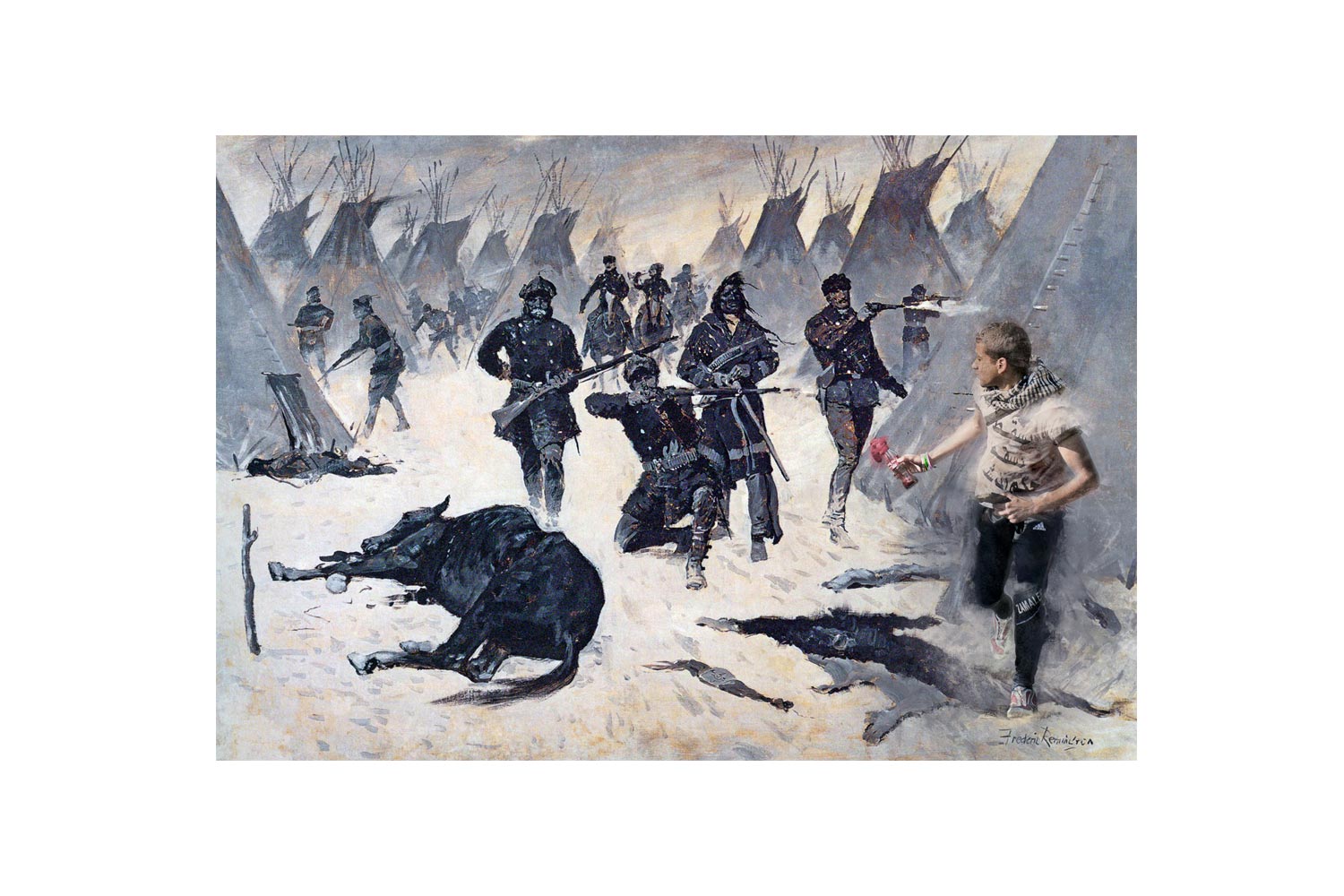

The Defeat of Crazy Horse

80 x 53 CM

The Desert of Assouan, Egypt by Sandord Robinson Gifford (1869)

34.5 x 80 cm

The Flight by Frederic Remington (1895)

55.5 x 80 cm

The Transgressorne

53 x 80 CM

Through the Smoke Sprang The Daring Soldier by Frederic Remington (1897), and Marilyn Monroe in Korea (1954).

53 x 80 cm