Aaru

Information Coming Soon.

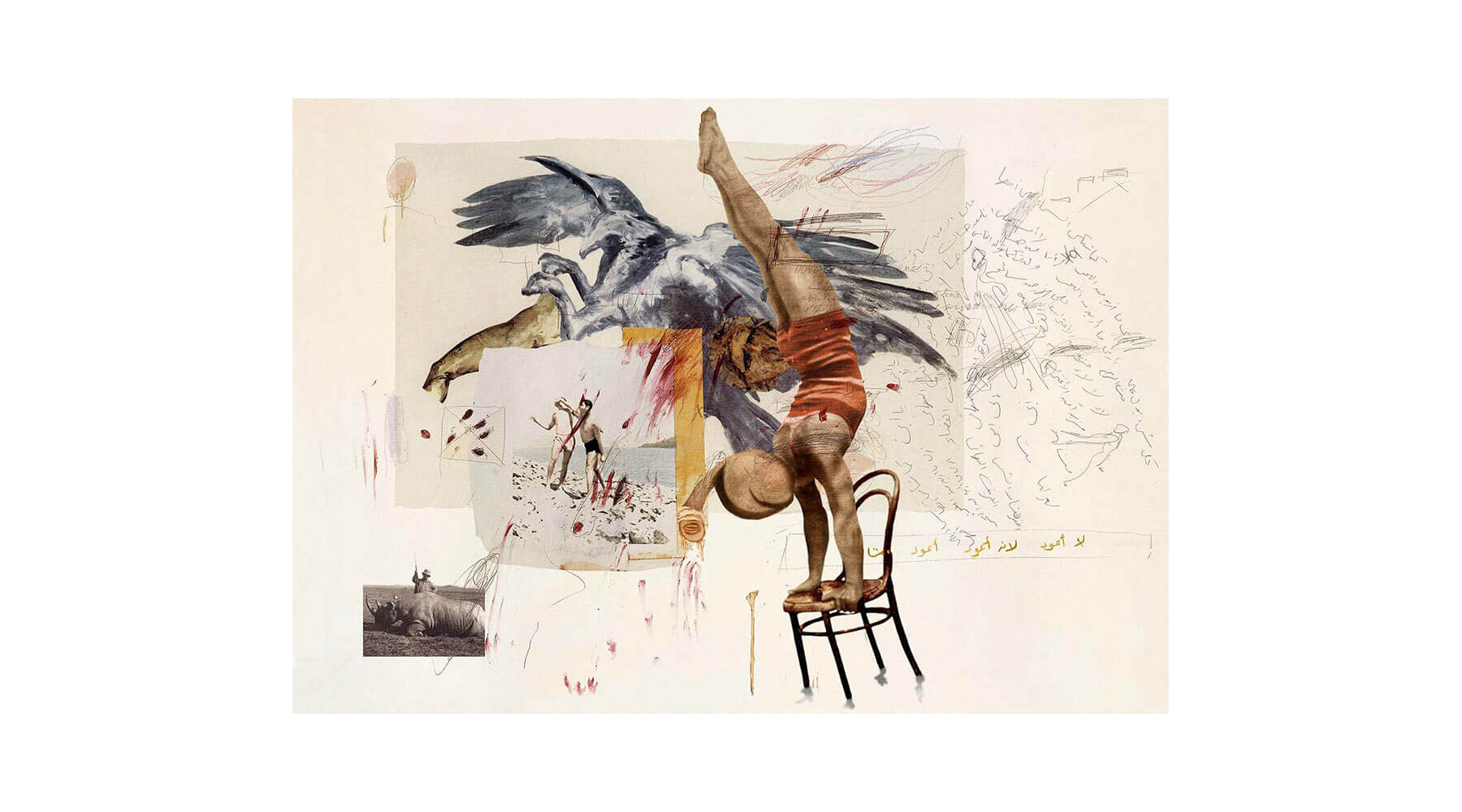

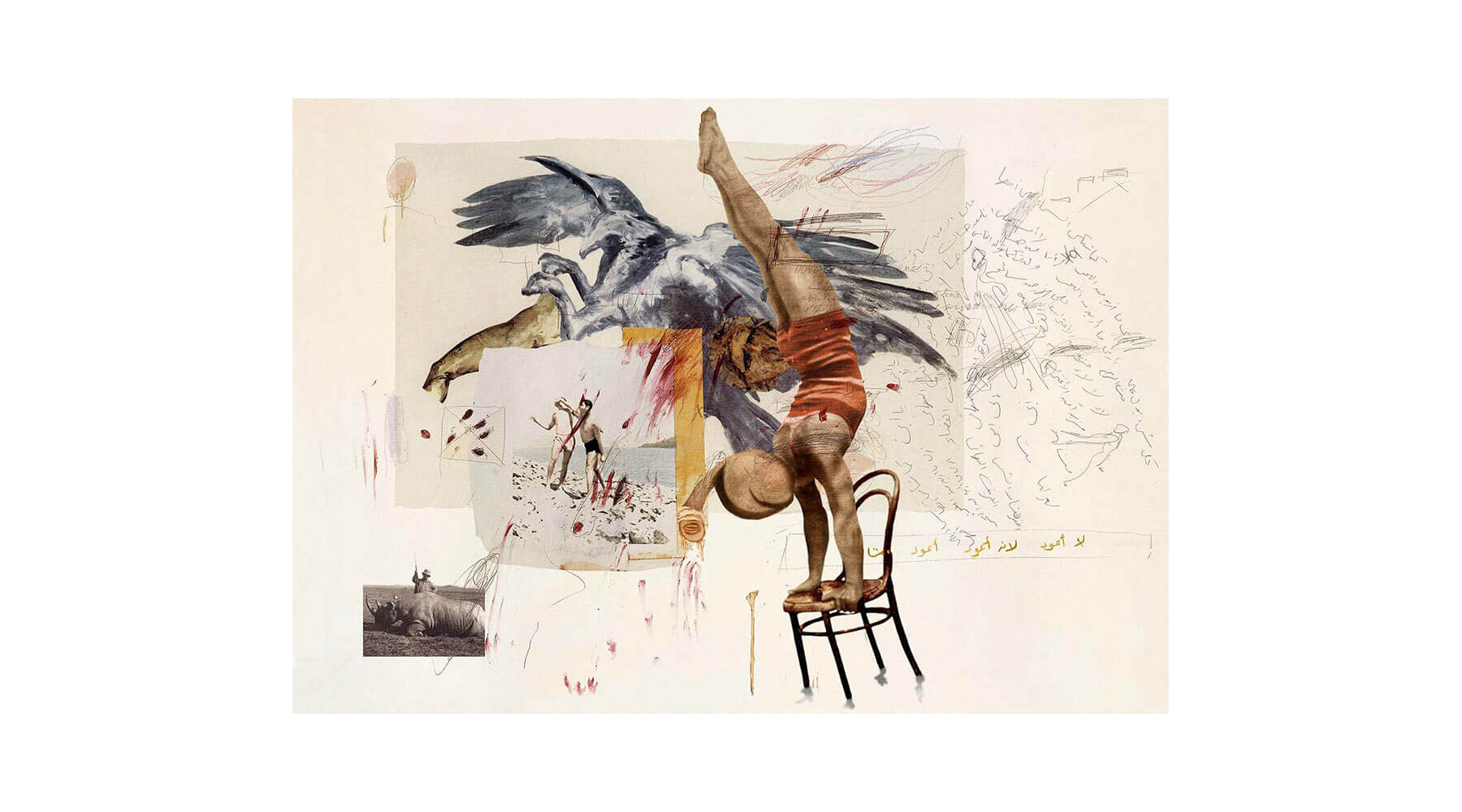

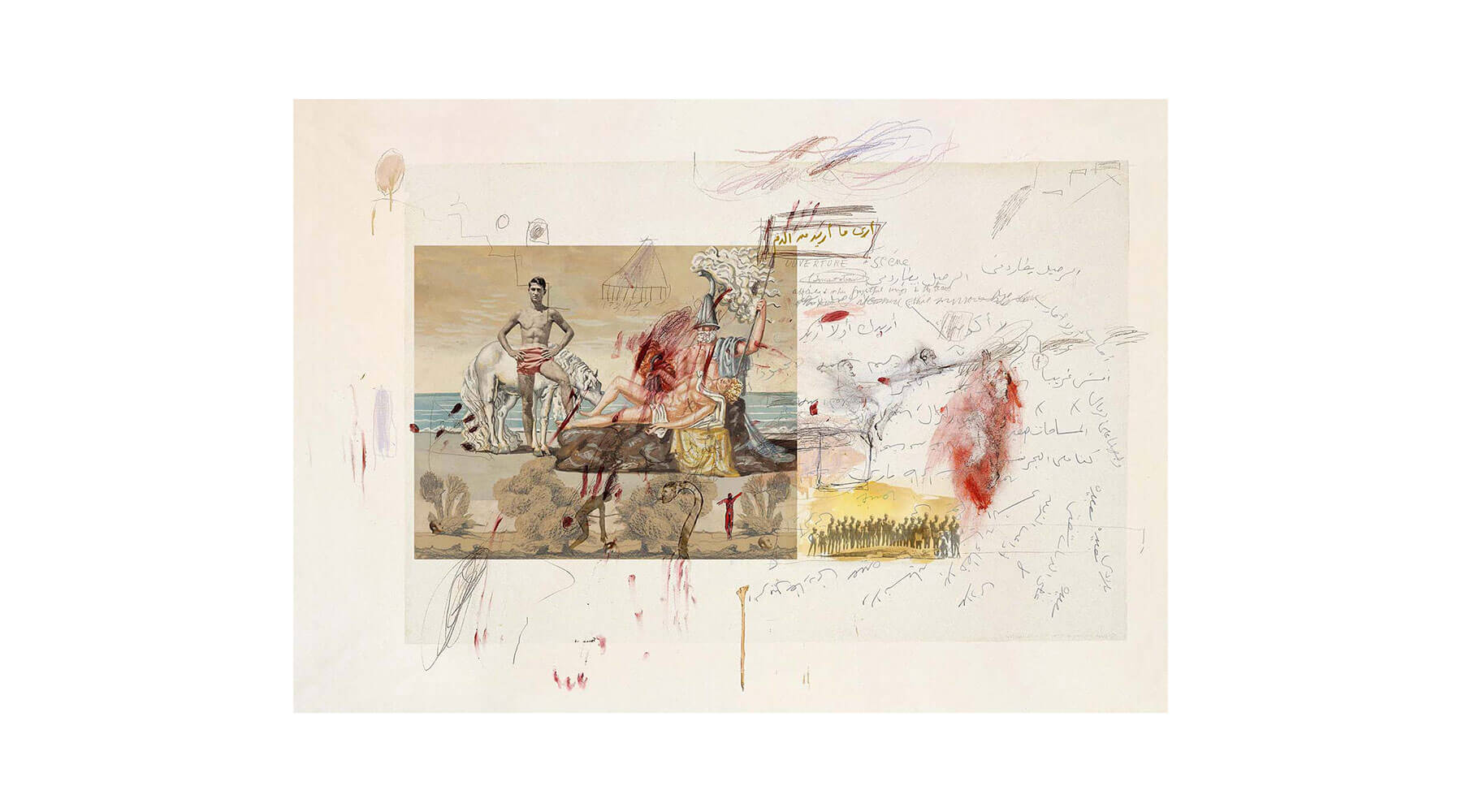

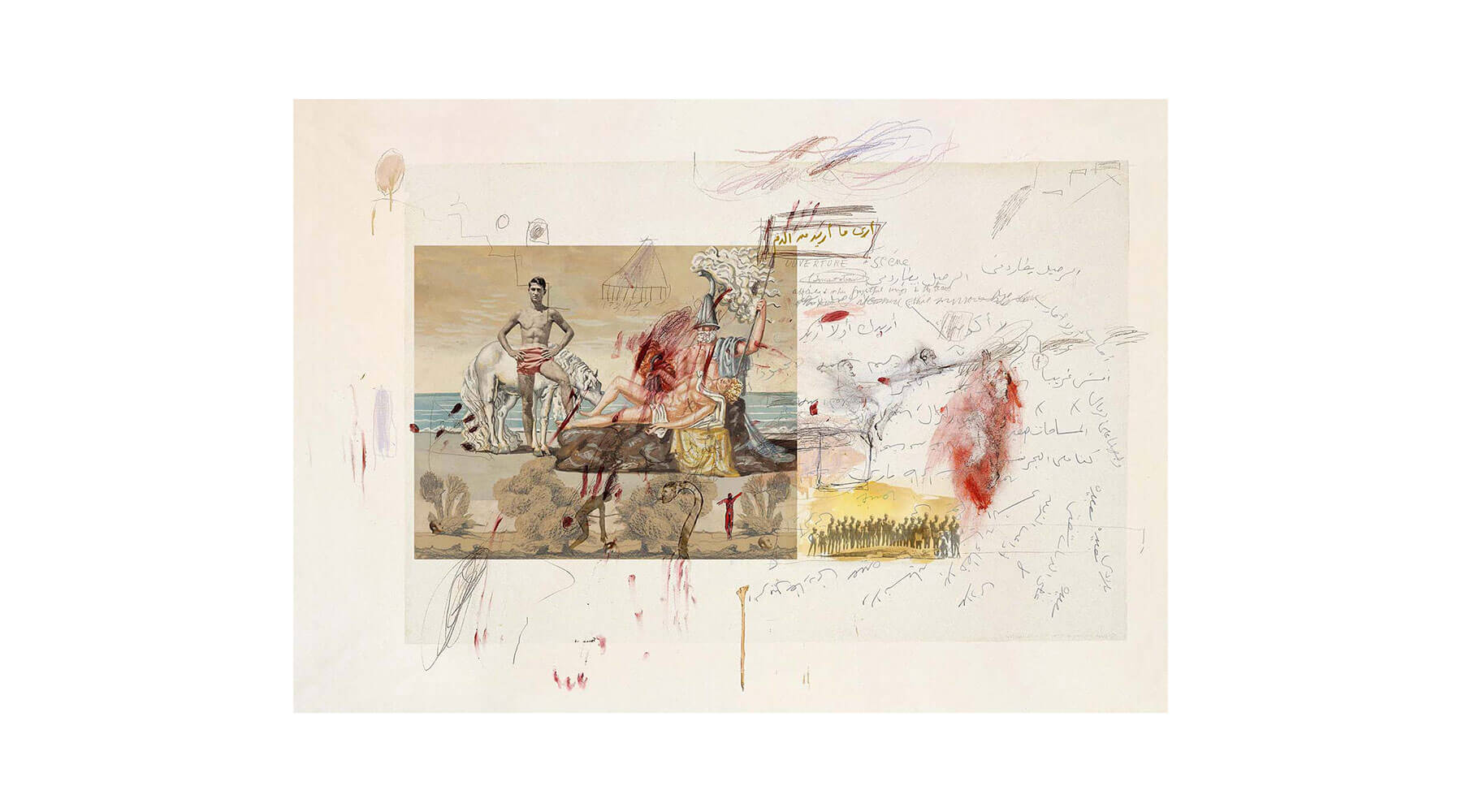

“We all draw upon one another and what has come before us. No one is really special or individual in thought or expression”, claims artist Nermine Hammam. Drawing on the past and those that have come before us is a central theme in Hammam’s new body of work, A’aru, a series of 22 digitally manipulated and hand painted images based on a collection of black and white vernacular photographs from the 1930s through to the 1960s taken on the beaches of Alexandria.

The manipulation, appropriation and amalgamation of her own images and that of others, is the method Hammam quickly felt most comfortable working with since she began creating photographic tableaux in 2001; her previous 20 years of experience in filmmaking and graphic design helping her hone her technical skills and providing her with a bank of images to borrow from. Although this recognisable style has previously been seen in the series Unfolding (2012) and Escaton (2009), in her current work, A’aru (2022), Hammam breaks down the strict adherence to reference and form and instead relies on the subconscious to navigate how the final image appears.

This sensorial manner of navigation echoes that of A’aru, the ancient Egyptian concept of the afterlife, also known as ‘The Field of Reeds’; a mirror image of life on Earth, where if one knows how to navigate the treacherous journey, one would be rewarded with an idealised vision of their life and be reunited with their loved ones. In the tomb chapel painting of the 18th Dynasty scribe Nebamun, the afterlife is depicted as a lush garden full of ripe trees and a pool teeming with fish and birds. In the vaulted crypt of a19th Dynasty artisan, we see Sennedjem and his wife Iineferti sowing seeds and harvesting grain in abundant fields surrounded by trees heavy with fruit.

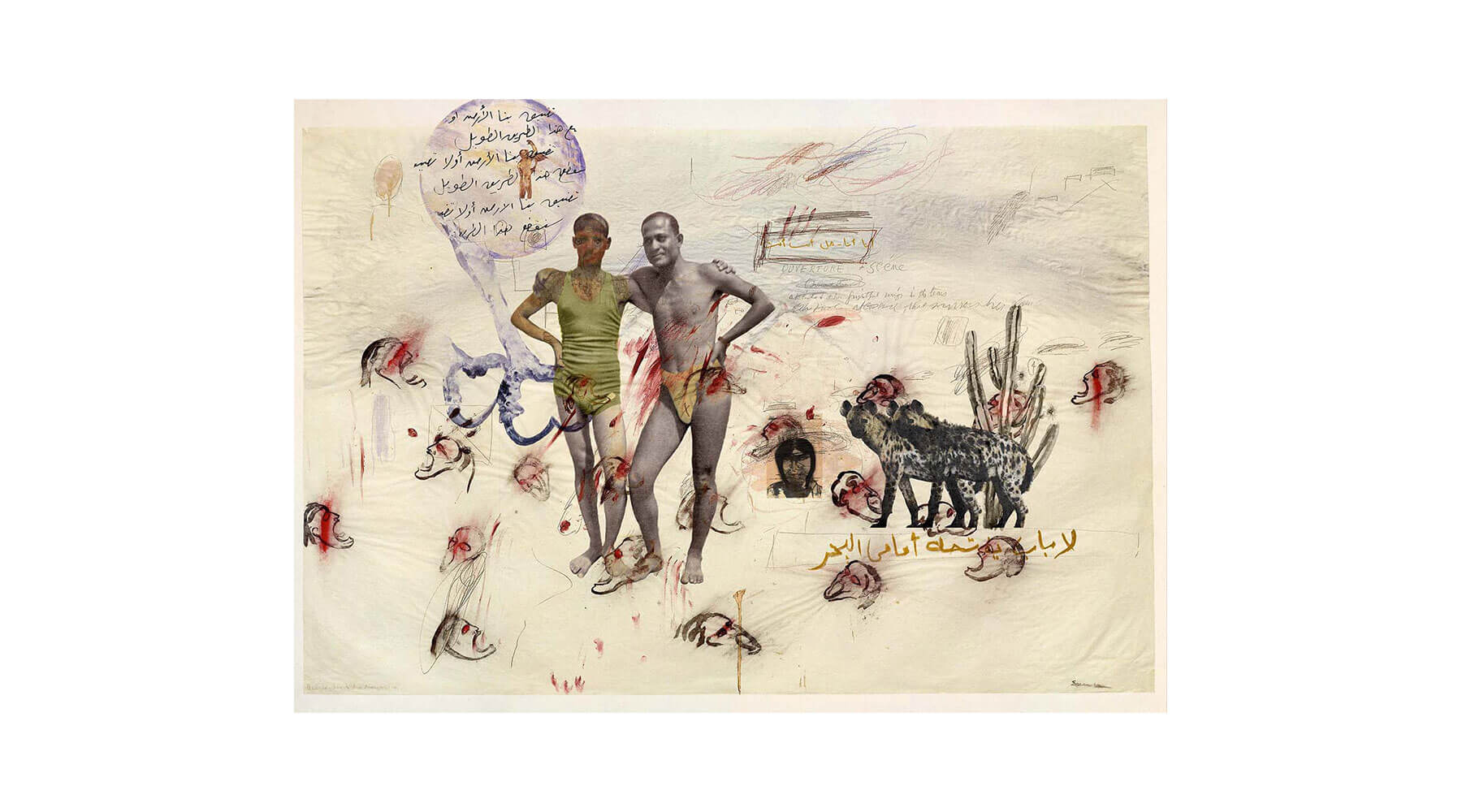

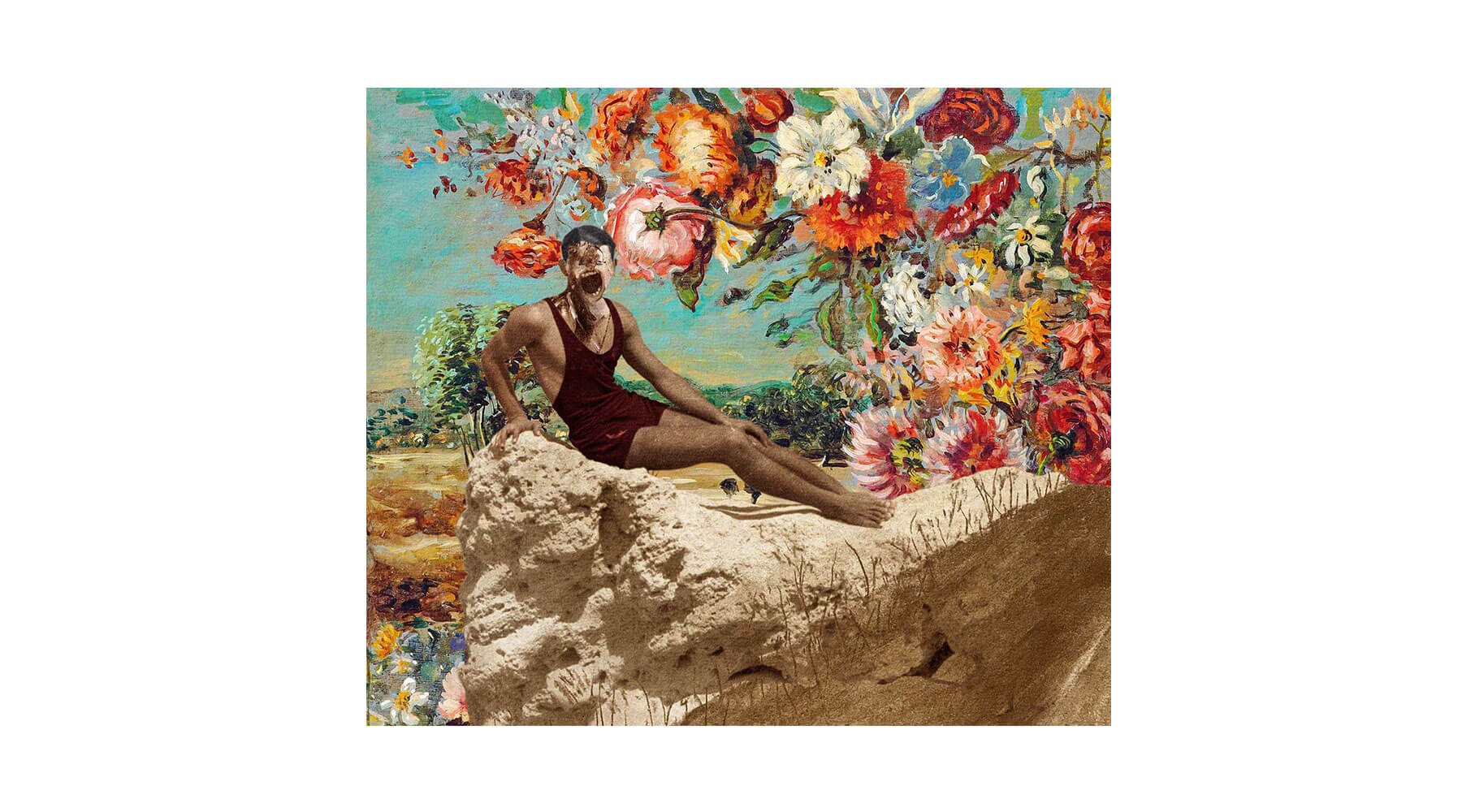

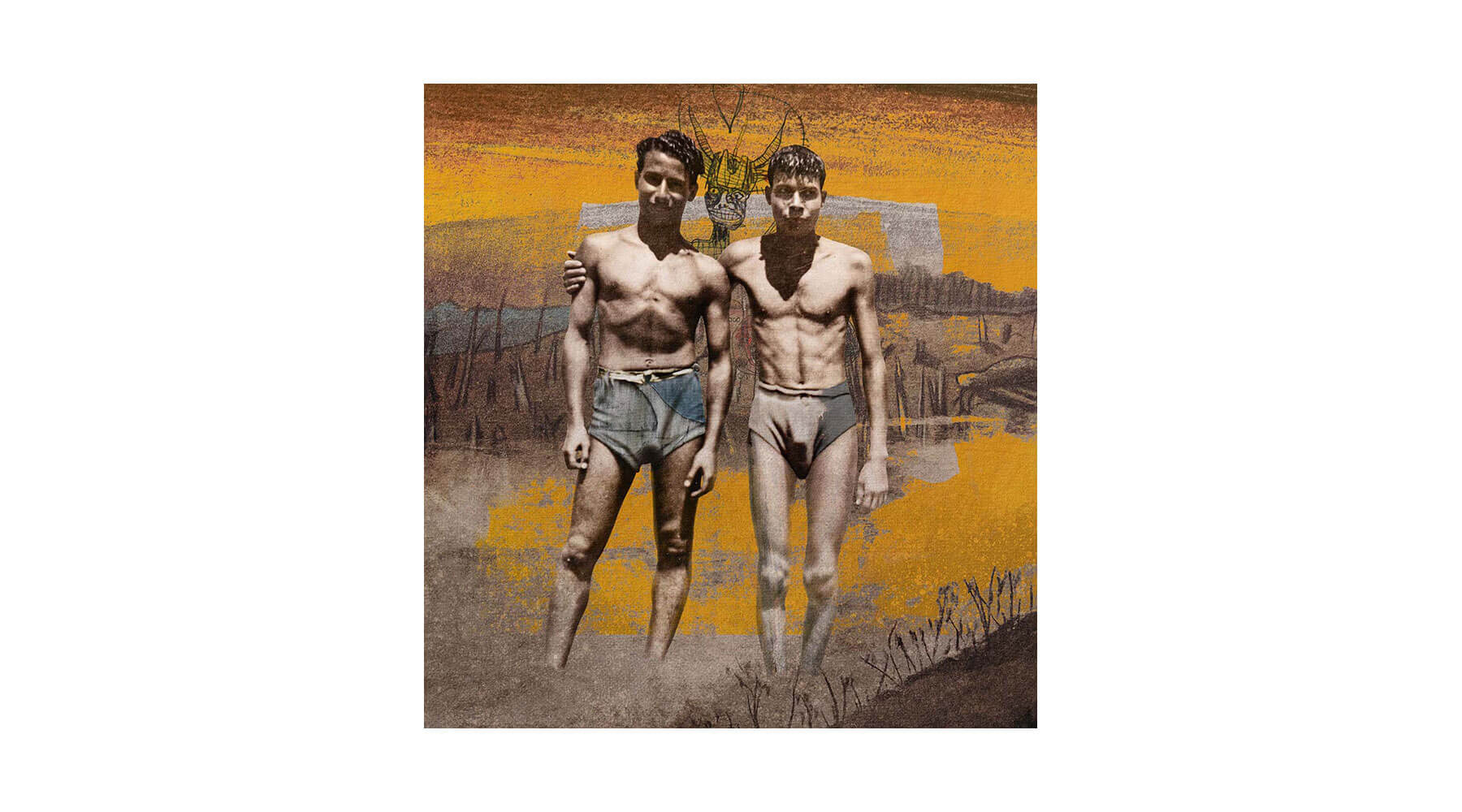

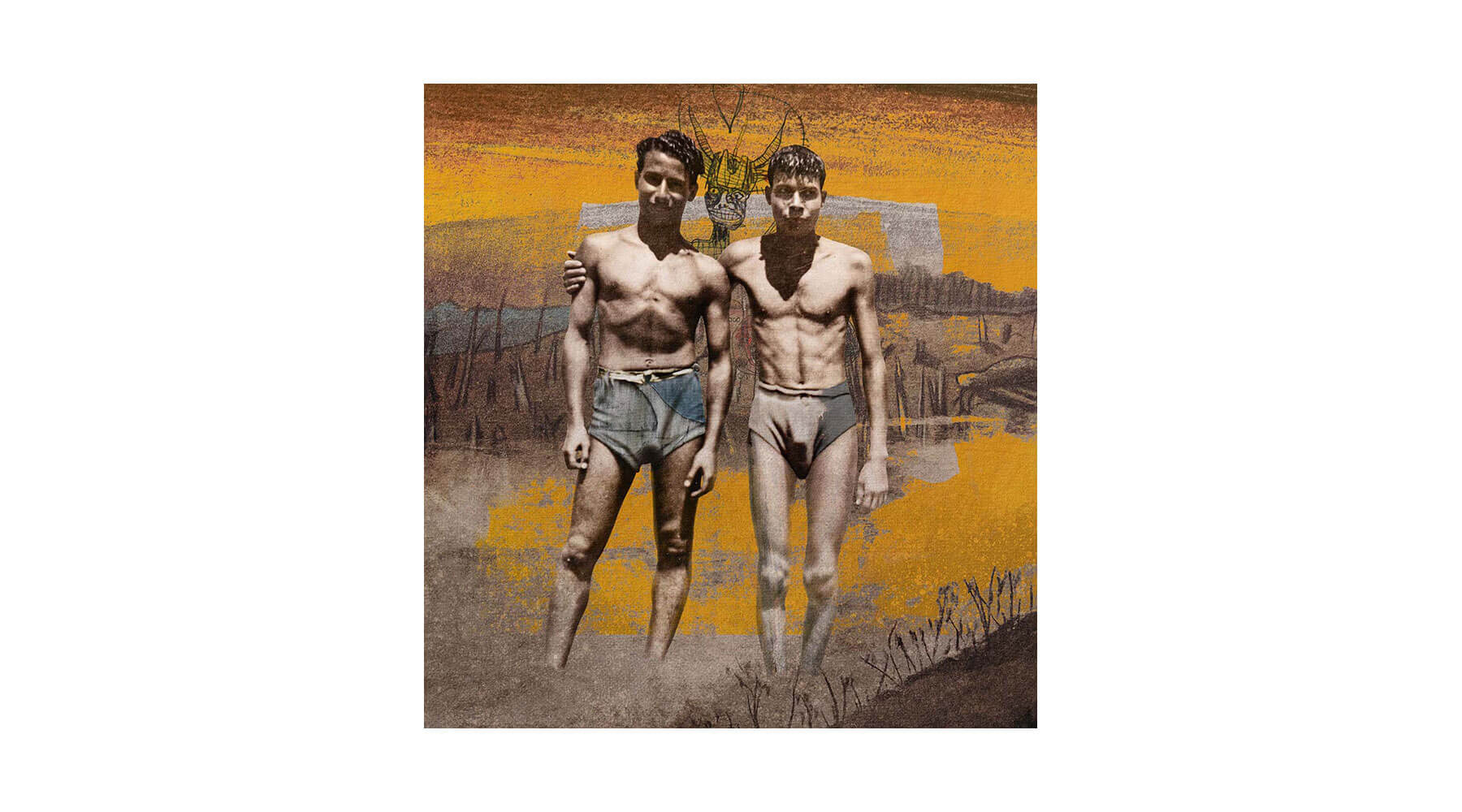

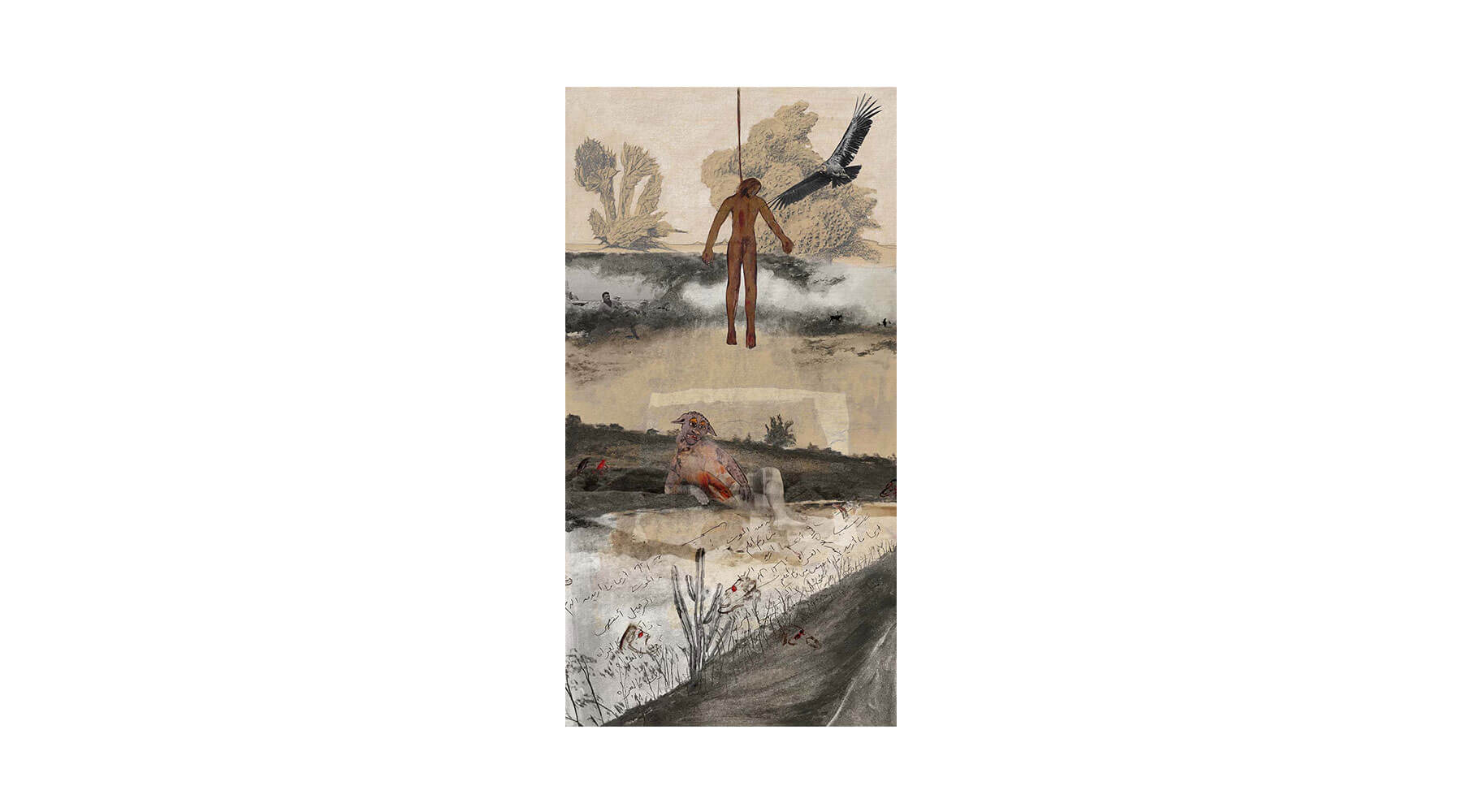

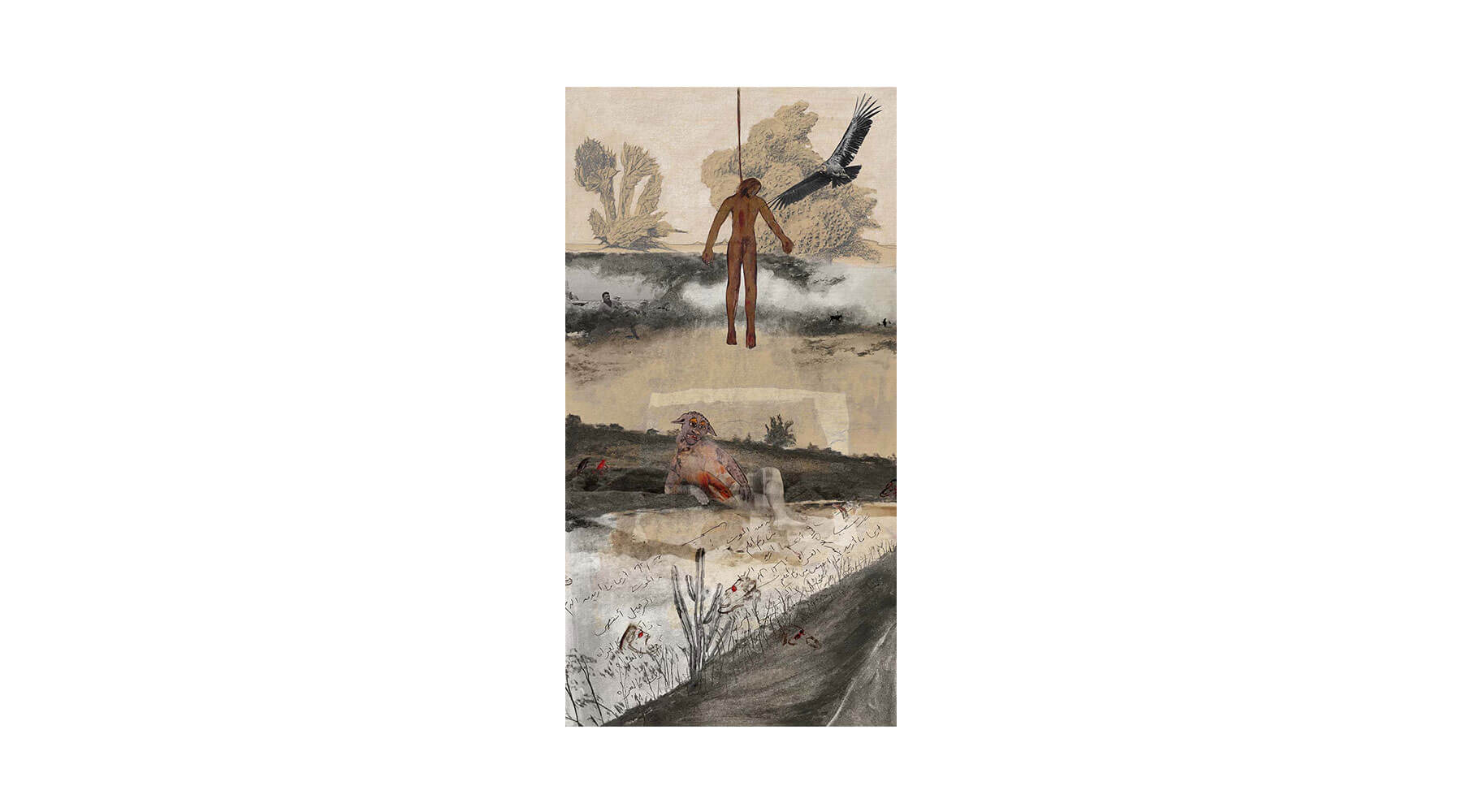

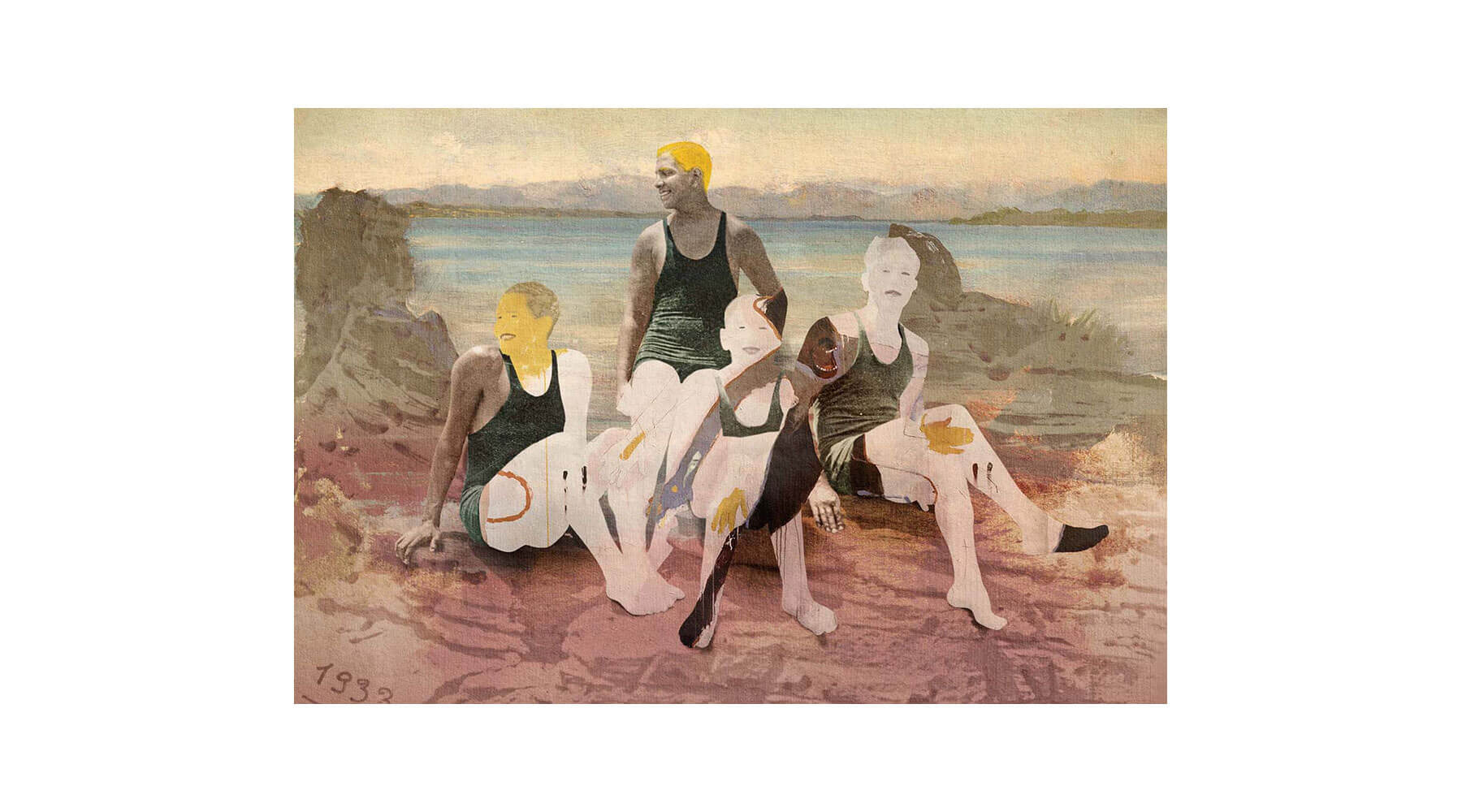

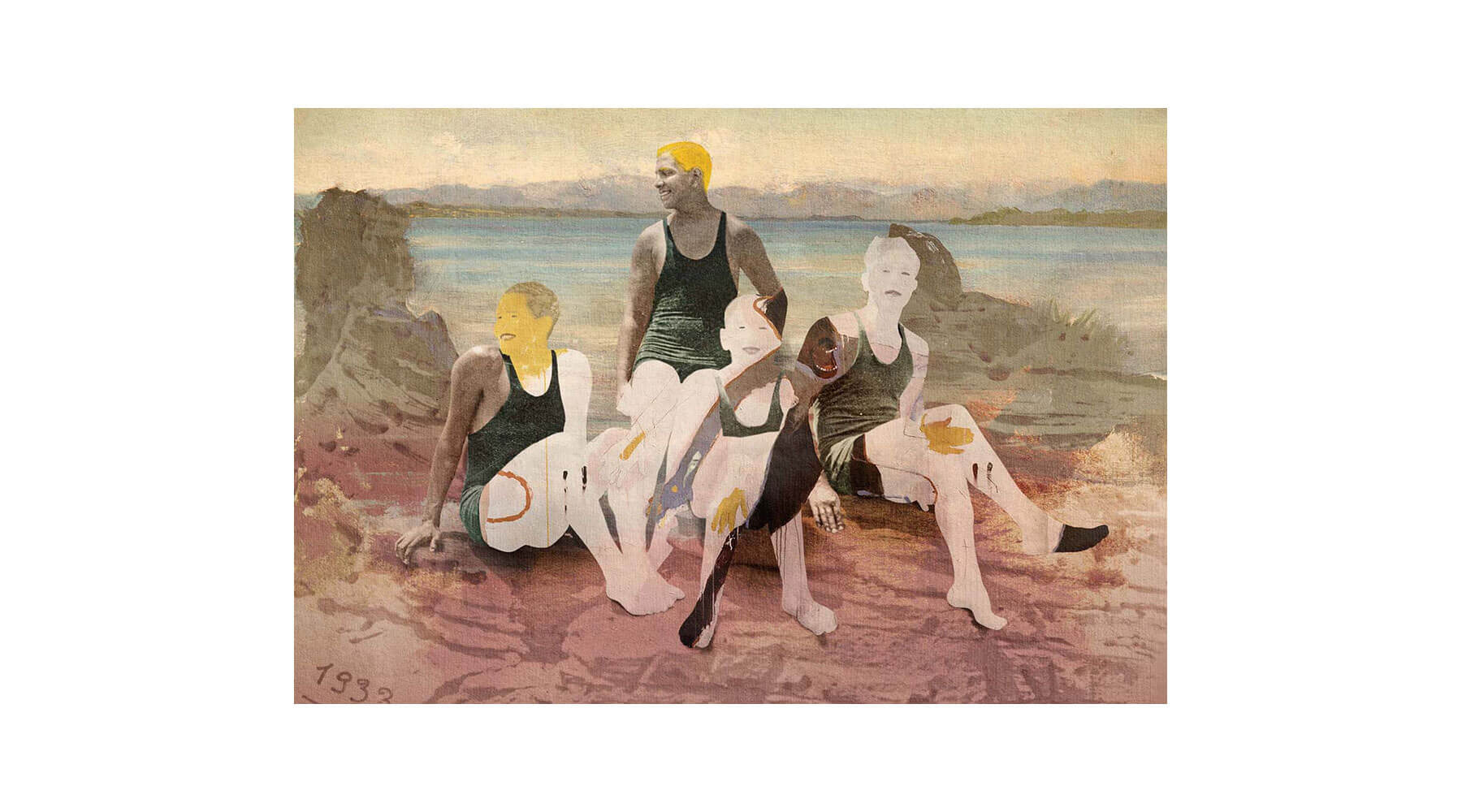

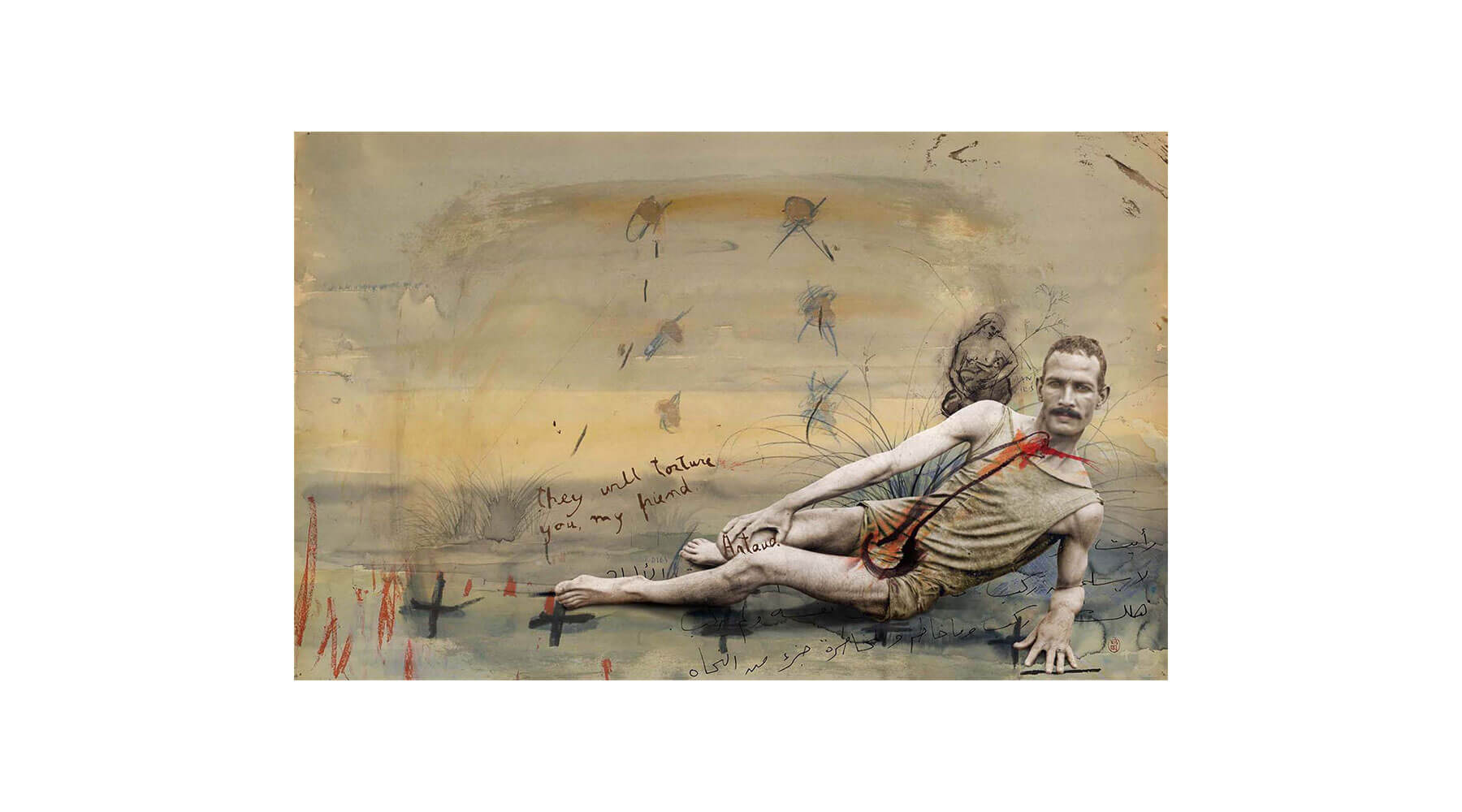

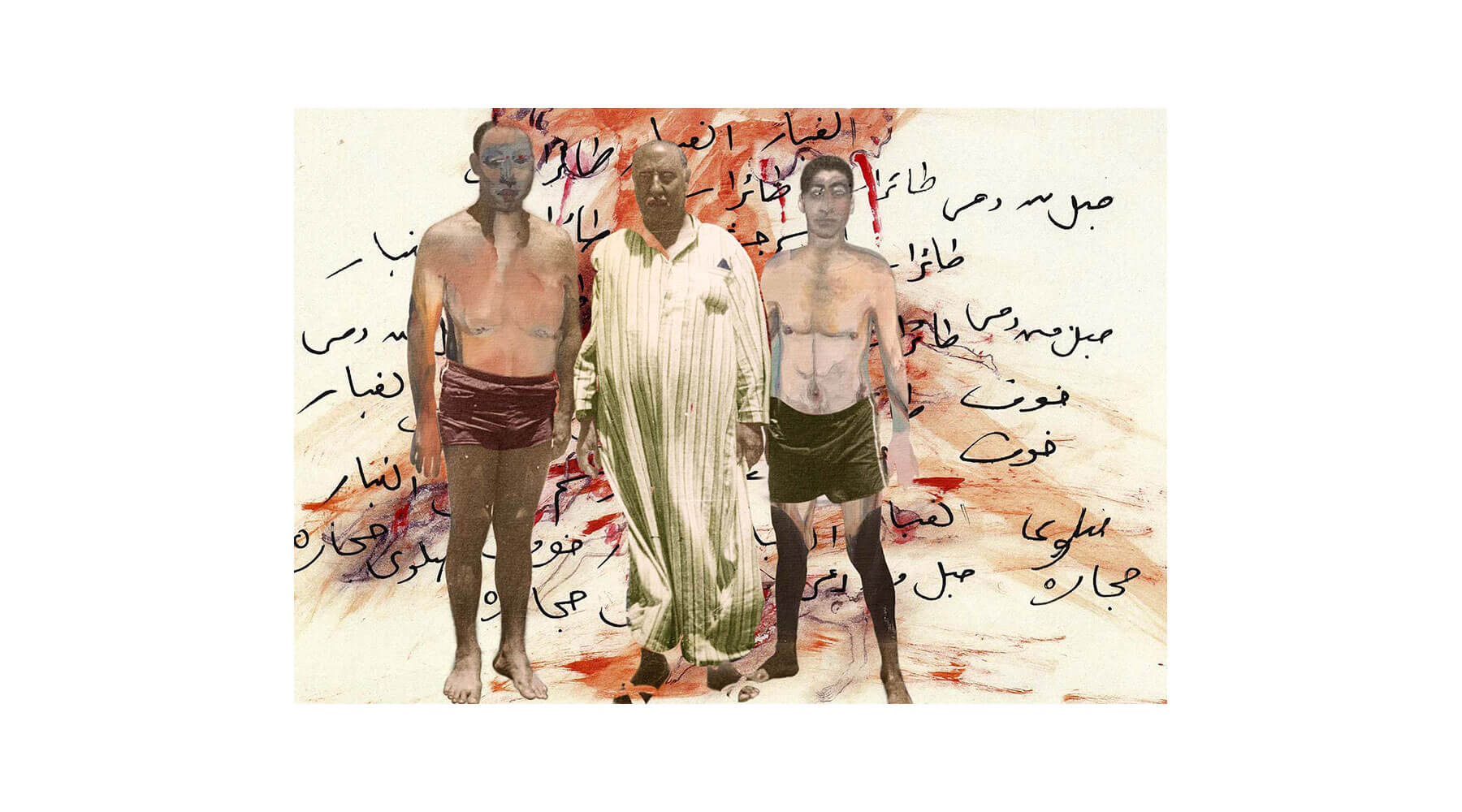

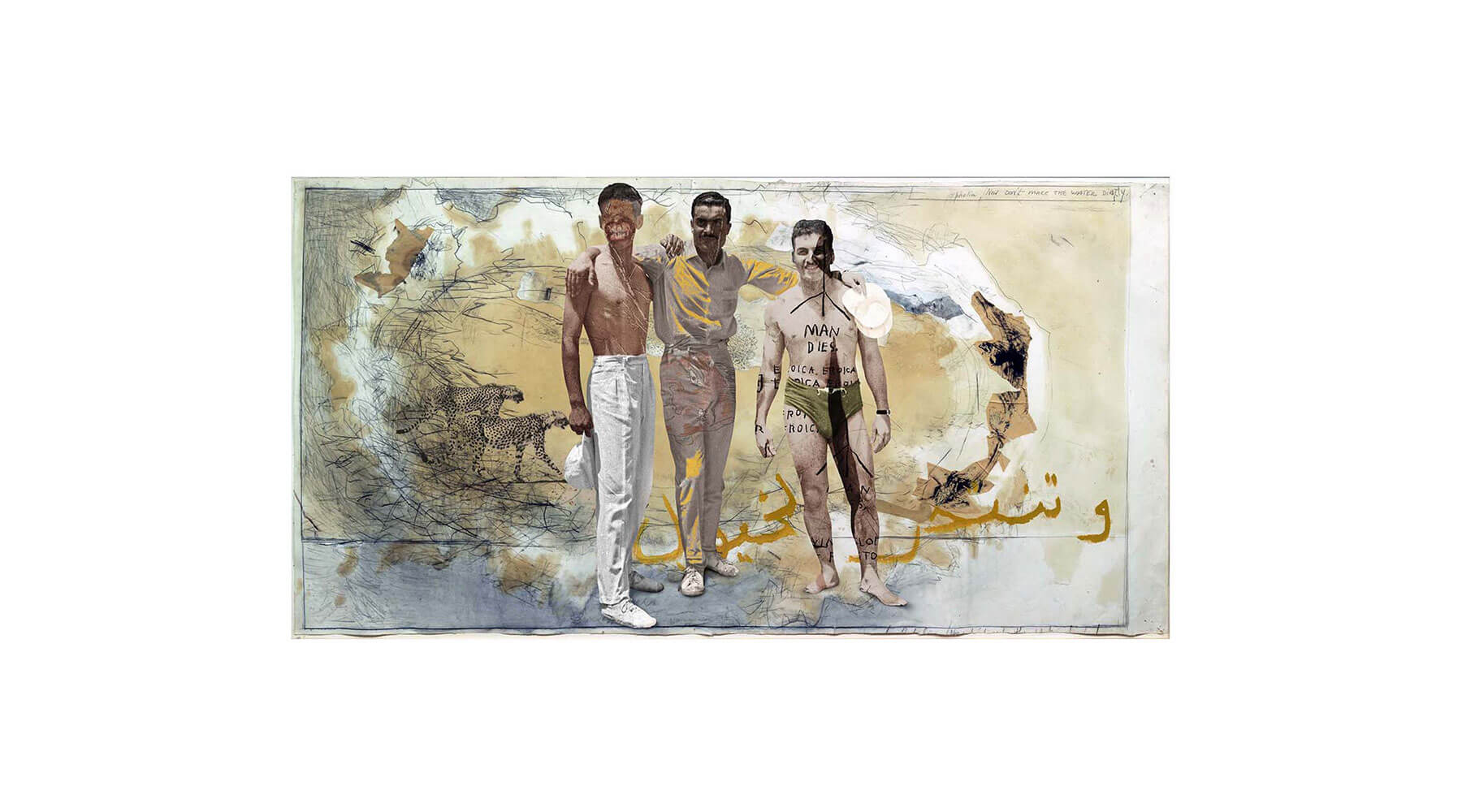

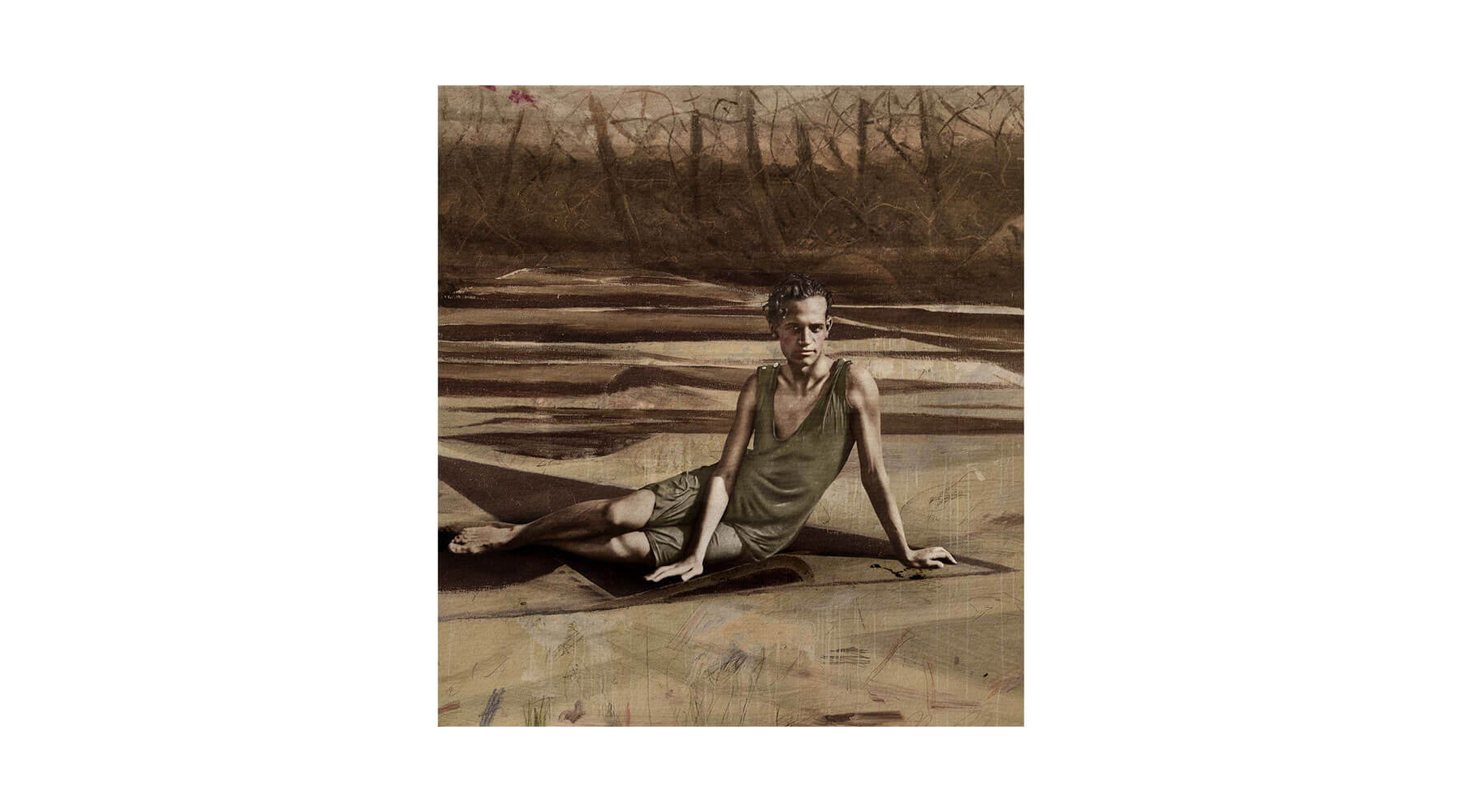

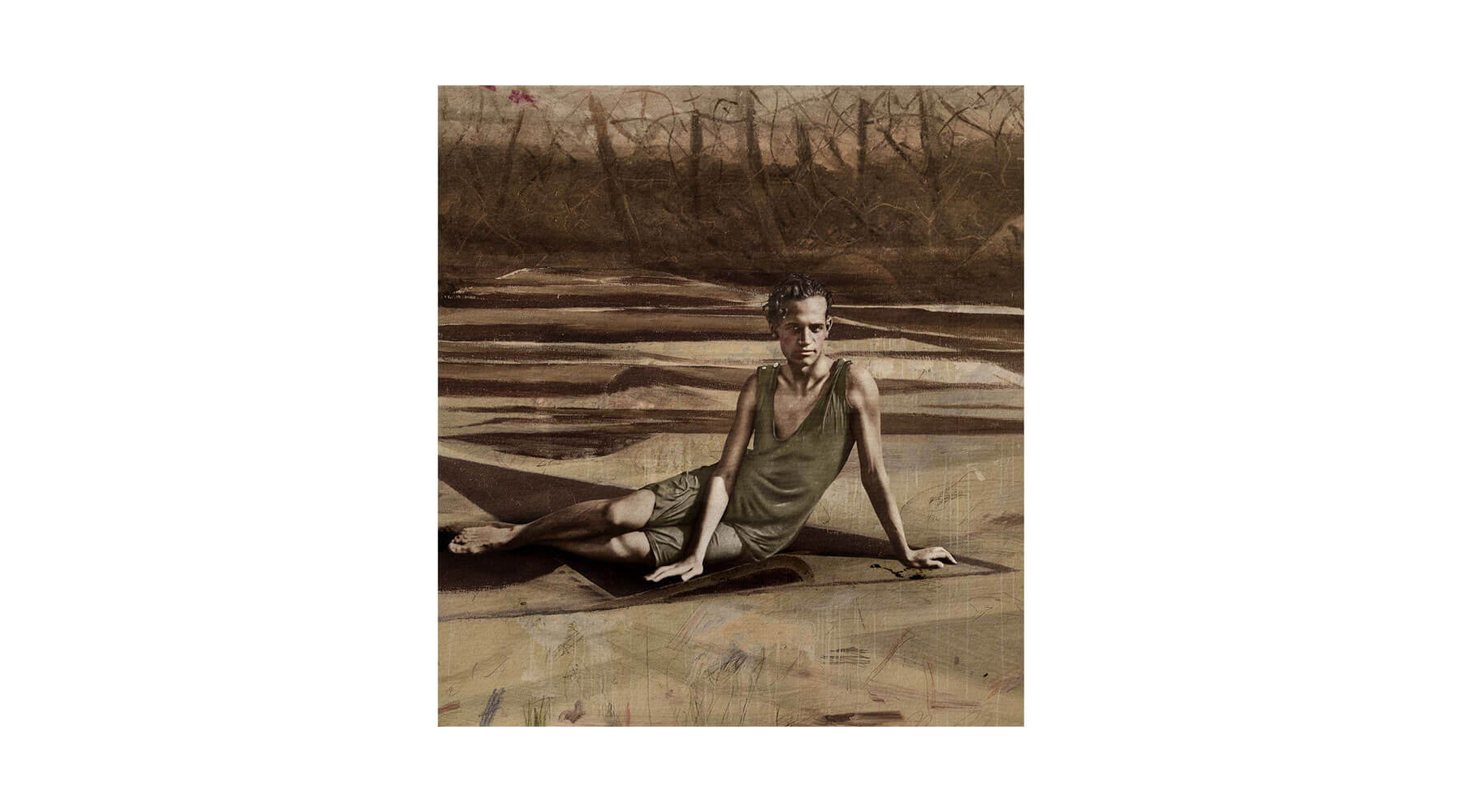

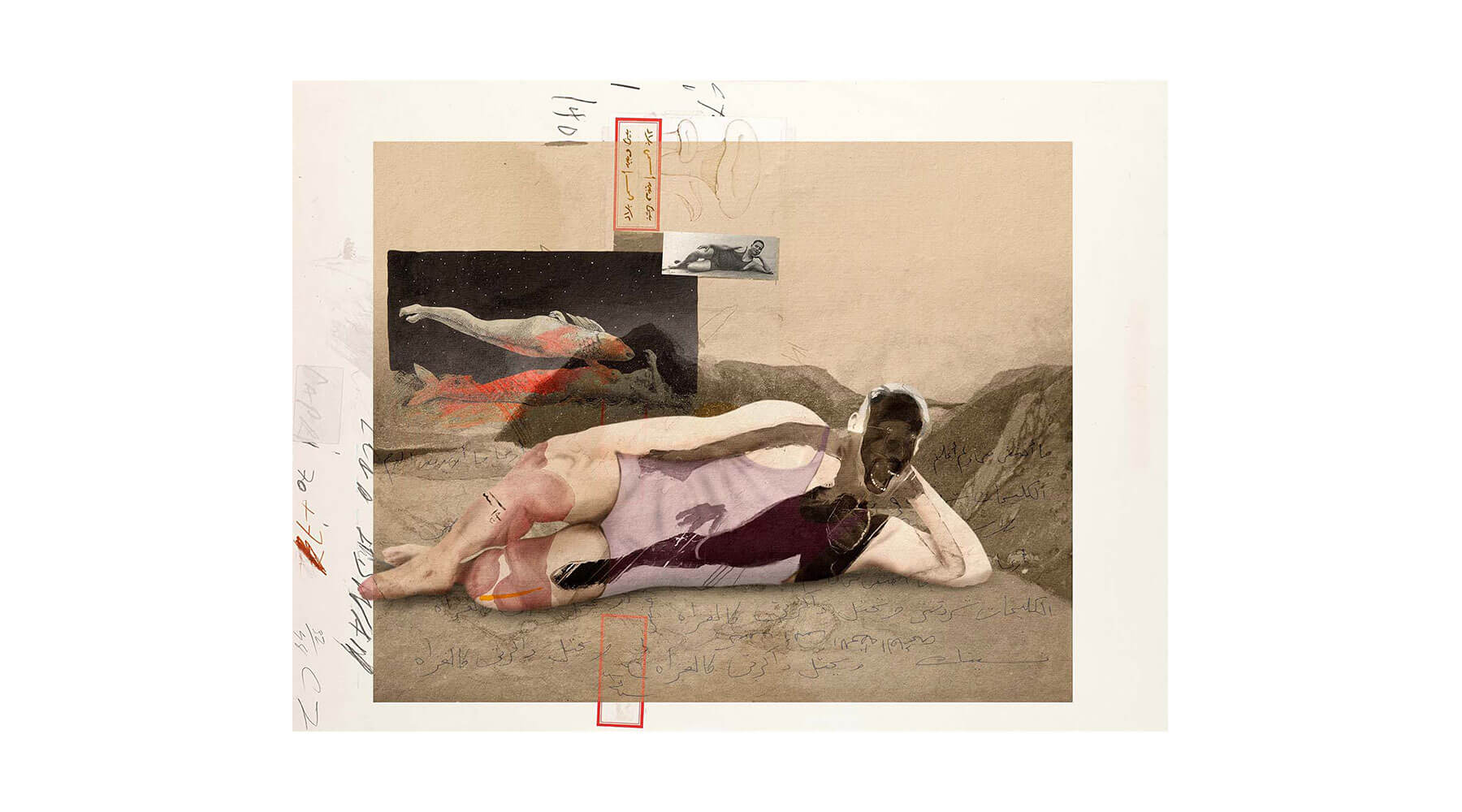

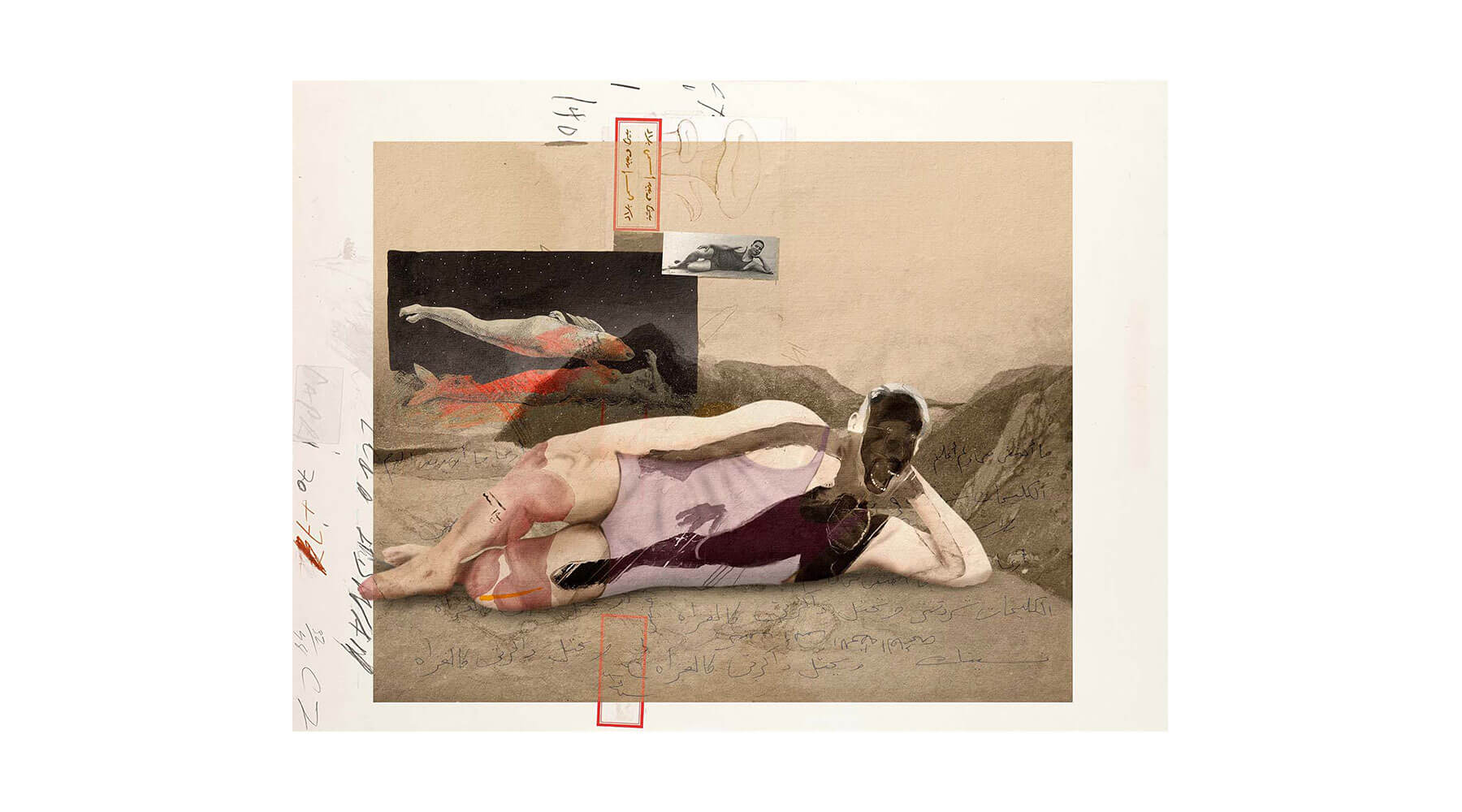

But in Hammam’s work the concept of A’aru is inverted. Rather than it being an idyllic world yet to come, Hammam shows us a once almost perfect world on the brink of destruction. For Hammam this endangered perfect world is the Alexandria of her past, a place she returned to every summer as a child, a place of perceived innocence. The base of each work is a black and white snap shot photograph of either an individual or group of men posing on the shores of Alexandria. Many recline languidly in classic beauty poses; hand on hip or hand on bent knee, others stand tall for the camera, arms around each other’s shoulders in friendly embraces, and others pose acrobatically or in make-believe fist fights.

In nearly all the original photographs the sea is naturally the background, the photographer using it as a backdrop to highlight the men’s beauty, strength and supposed affinity with nature. But Hammam exploits this backdrop using it as her canvas on which to explore and challenge memory and nostalgia employing the Jungian theory of ‘the collective unconscious’. According to the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, every person is born with a collection of imagery and knowledge inherited from their ancestors and shared by all. Unaware of what thoughts and imagery lie in our subconscious, in times of crisis the psyche naturally taps into this unknown field conjuring up ‘archetypes’ or universal concepts; the signs, symbols and patterns of behaviour traced since time immemorial, that form the basis of all mythologies, that silently motivate us and help give meaning to our world.

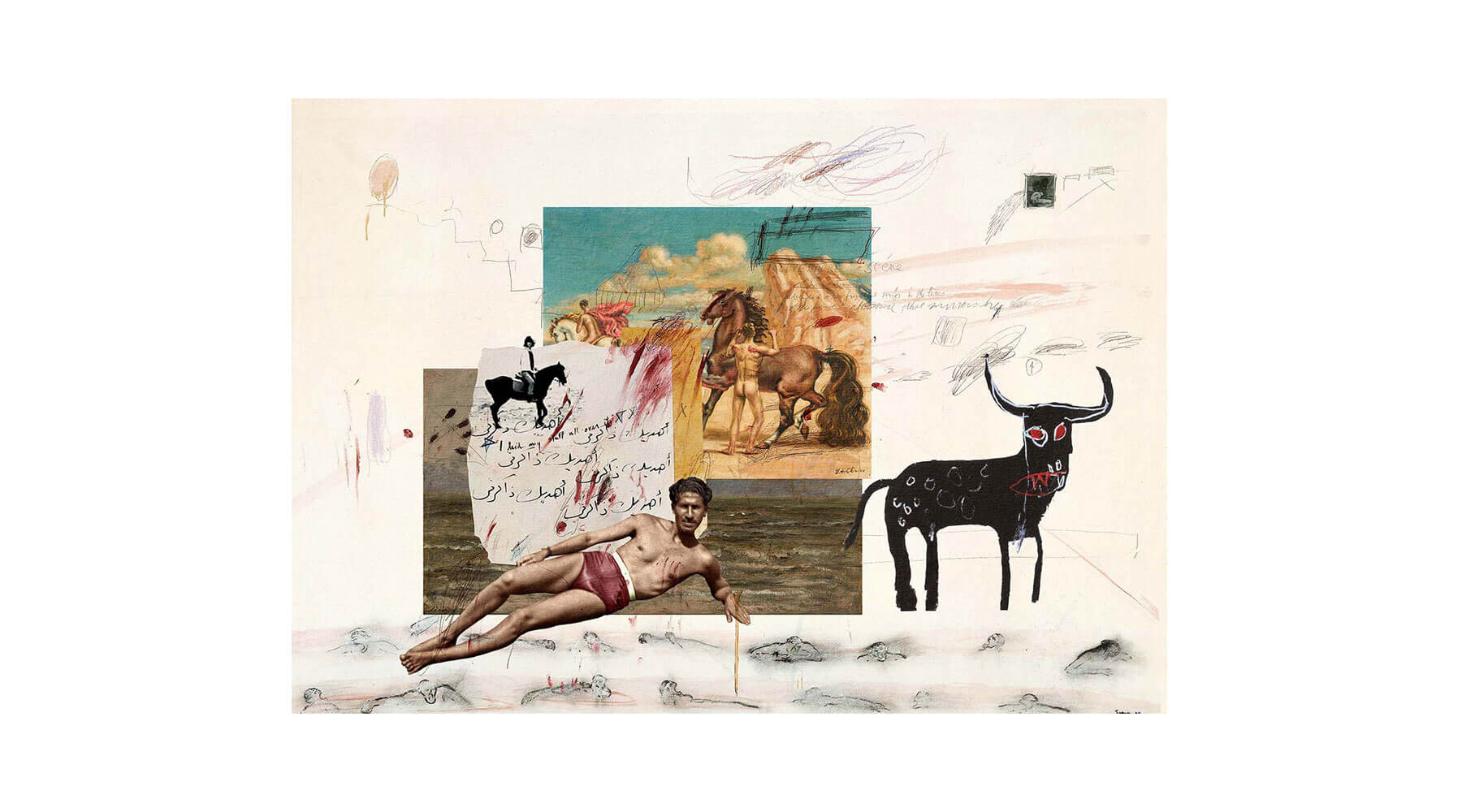

The works of artists such as Paul Nash, Peter Beard, Giorgio di Chirico, Nancy Spero and Francis Bacon, are just part of the collective unconscious that Hammam taps into when working, seeing the imagery that these artists use as an already borrowed symbolic universal language that can continue to be borrowed from. Background colours and motifs are extracted from works by the likes of: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Claude Manet, Georgia O’Keeffe, Mark Rothko, Michael Leonard and Paul Gauguin, creating images that appear instantly familiar and yet completely disrupted and unsettling.

This illustrative, sketchbook-like approach to building an image marks a departure for Hammam from the more meticulous, controlled and literal way of working that we see in previous works such as Upekkha (2011) and Wétiko: Cowboys and Indigenes (2014) and is most visible in the first eleven works in the series A’aru.

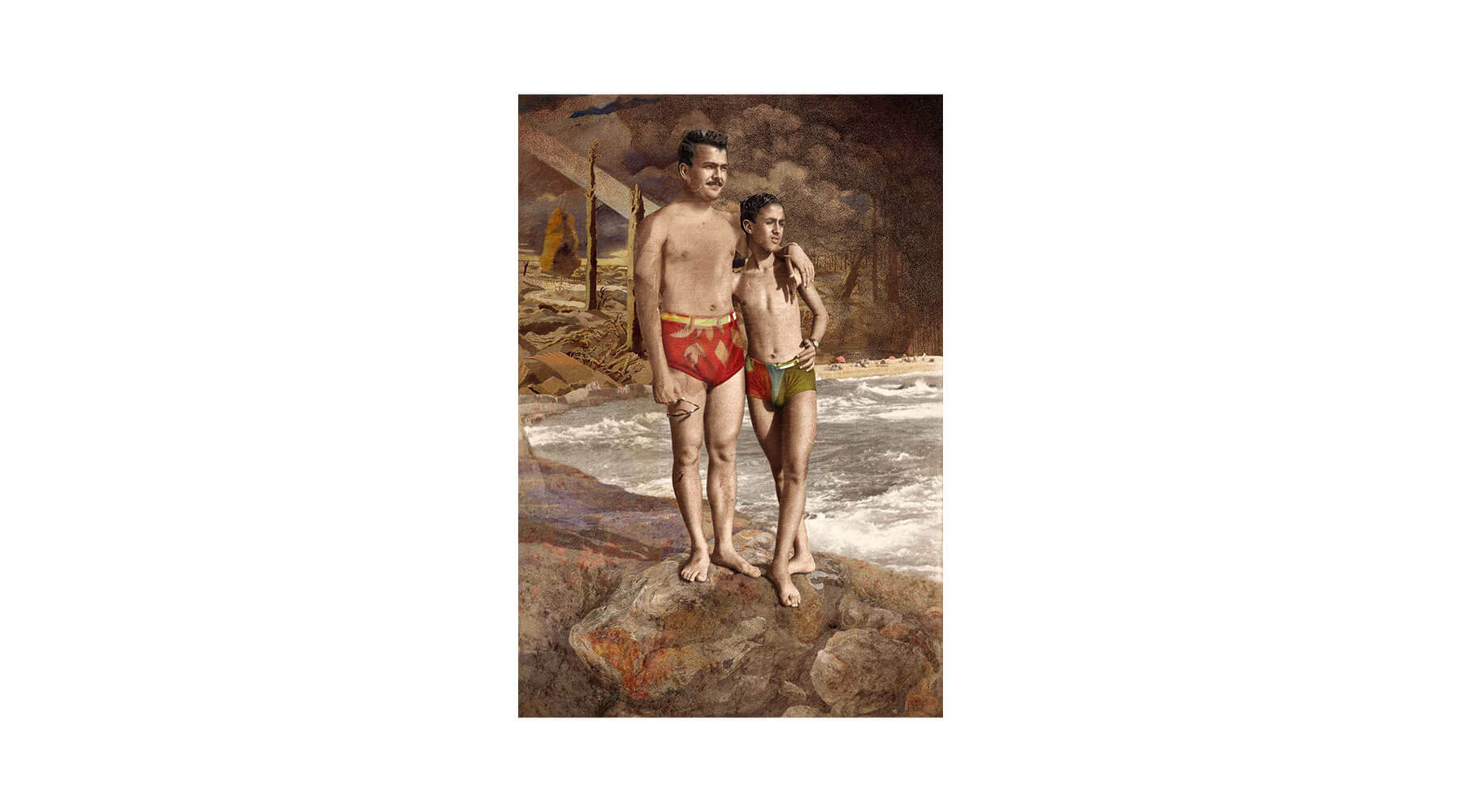

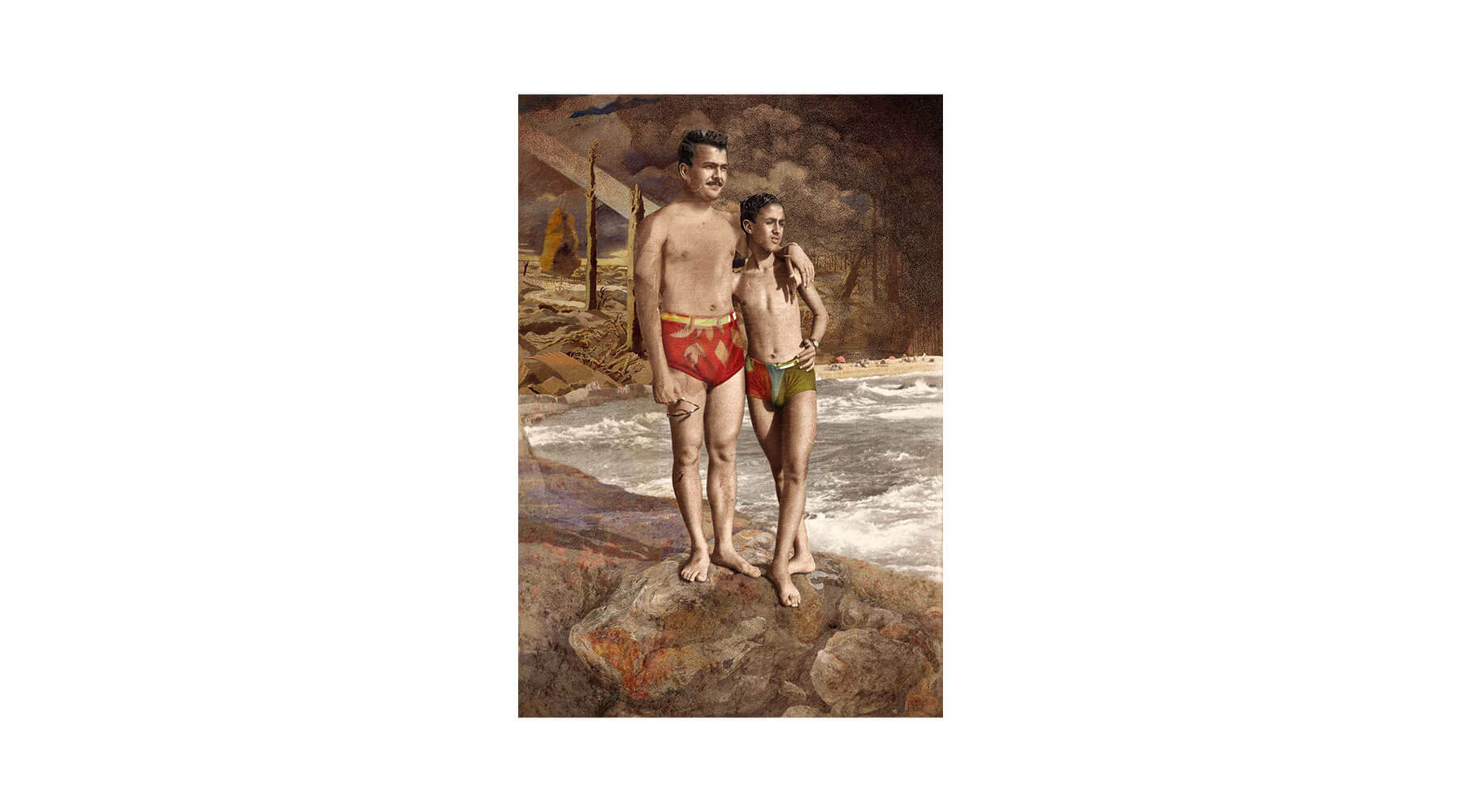

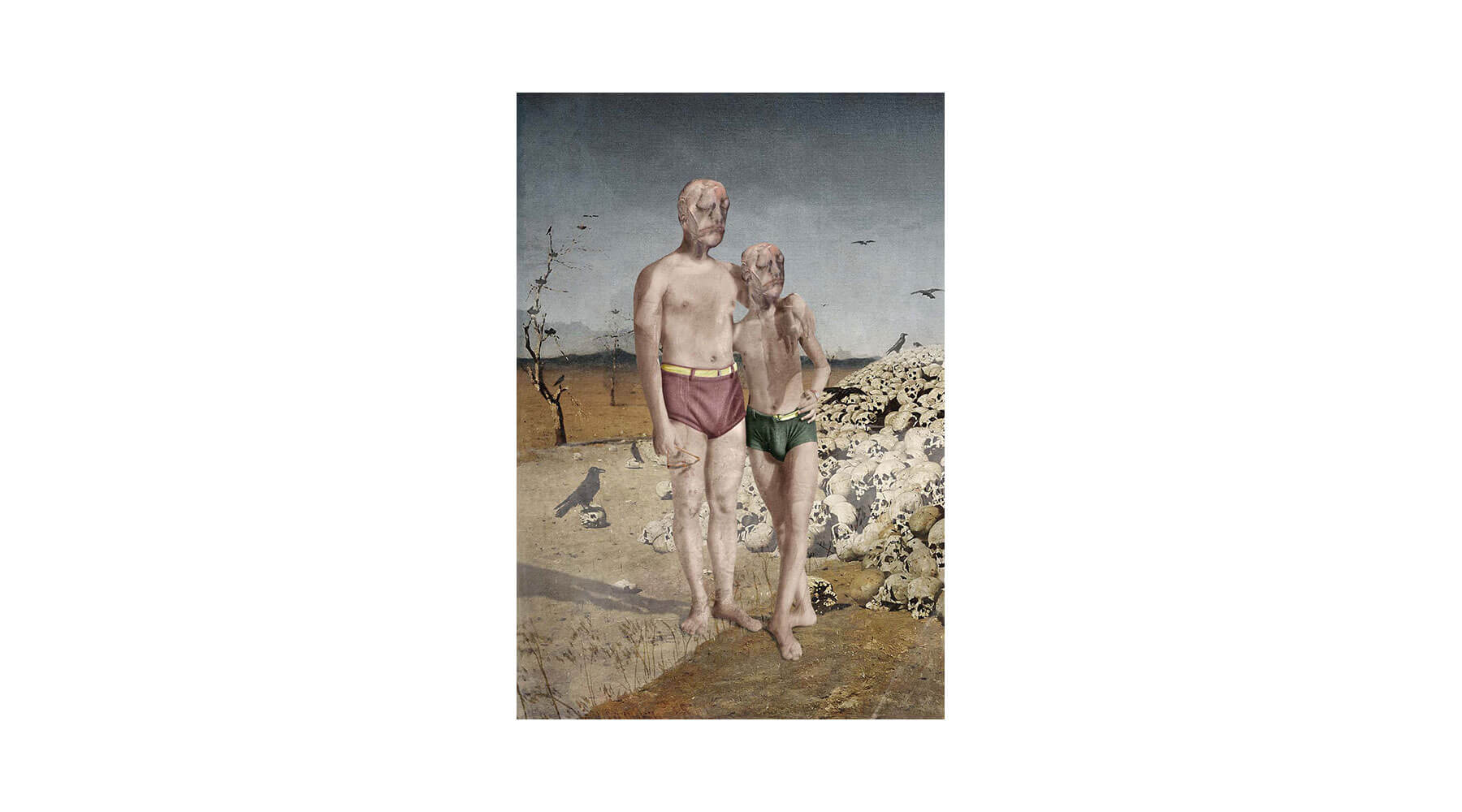

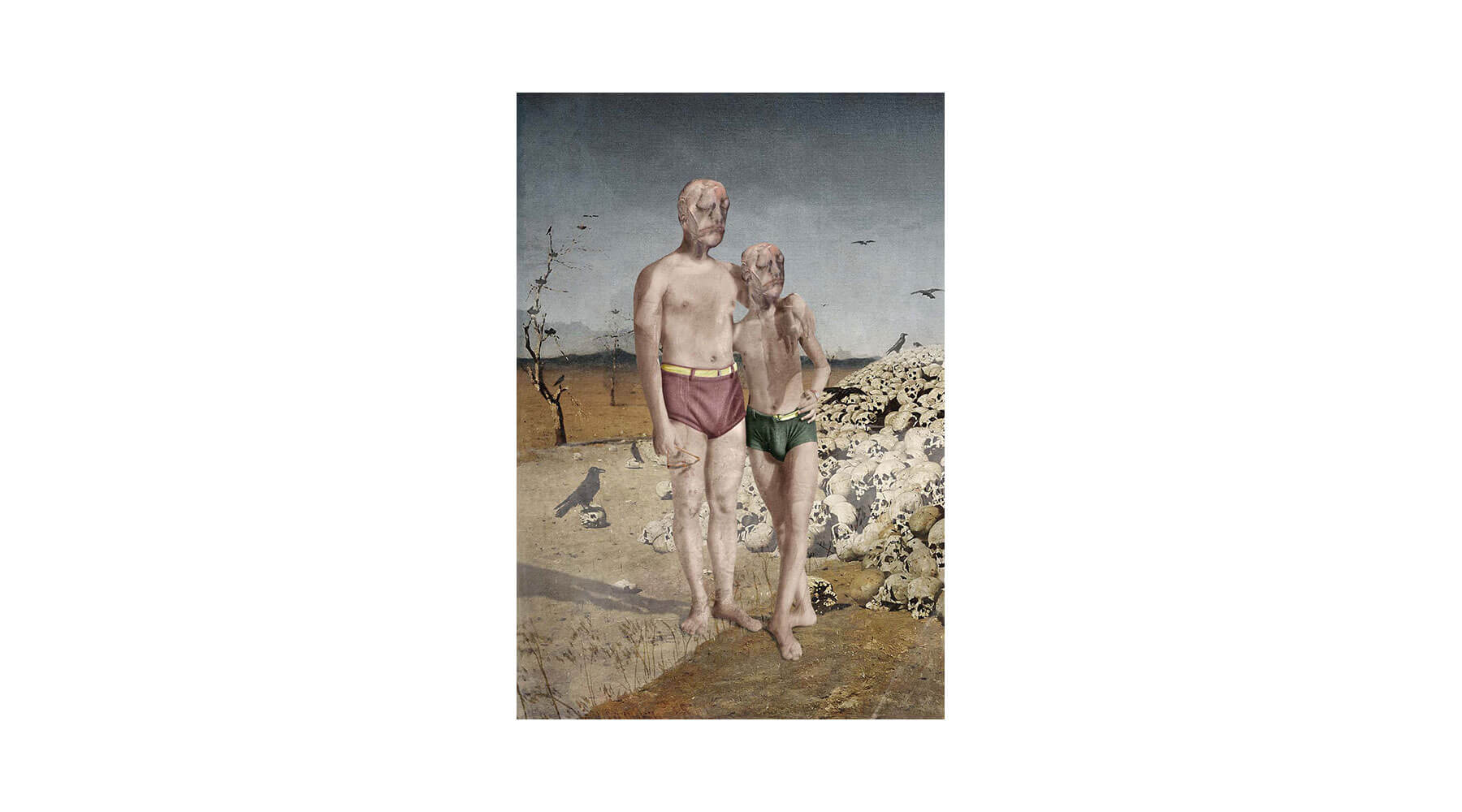

In Cosmic Mutations 1, a father and son stand elegantly looking out at sea. With their arms gently around each other and their bodies sculpted by the sun it appears to be a celebration or marking of the transition of boyhood into manhood. Behind them waves crash onto a rocky shore while a scorched post world war landscape continues to smoulder. Are they contemplating a brighter future or is the son unaware of the land being bequeathed to him? In Cosmic Mutations 2, the father and son have lost their virility, both their faces morphed into the same grimaces, the desolate landscape now laid solemnly at their feet.

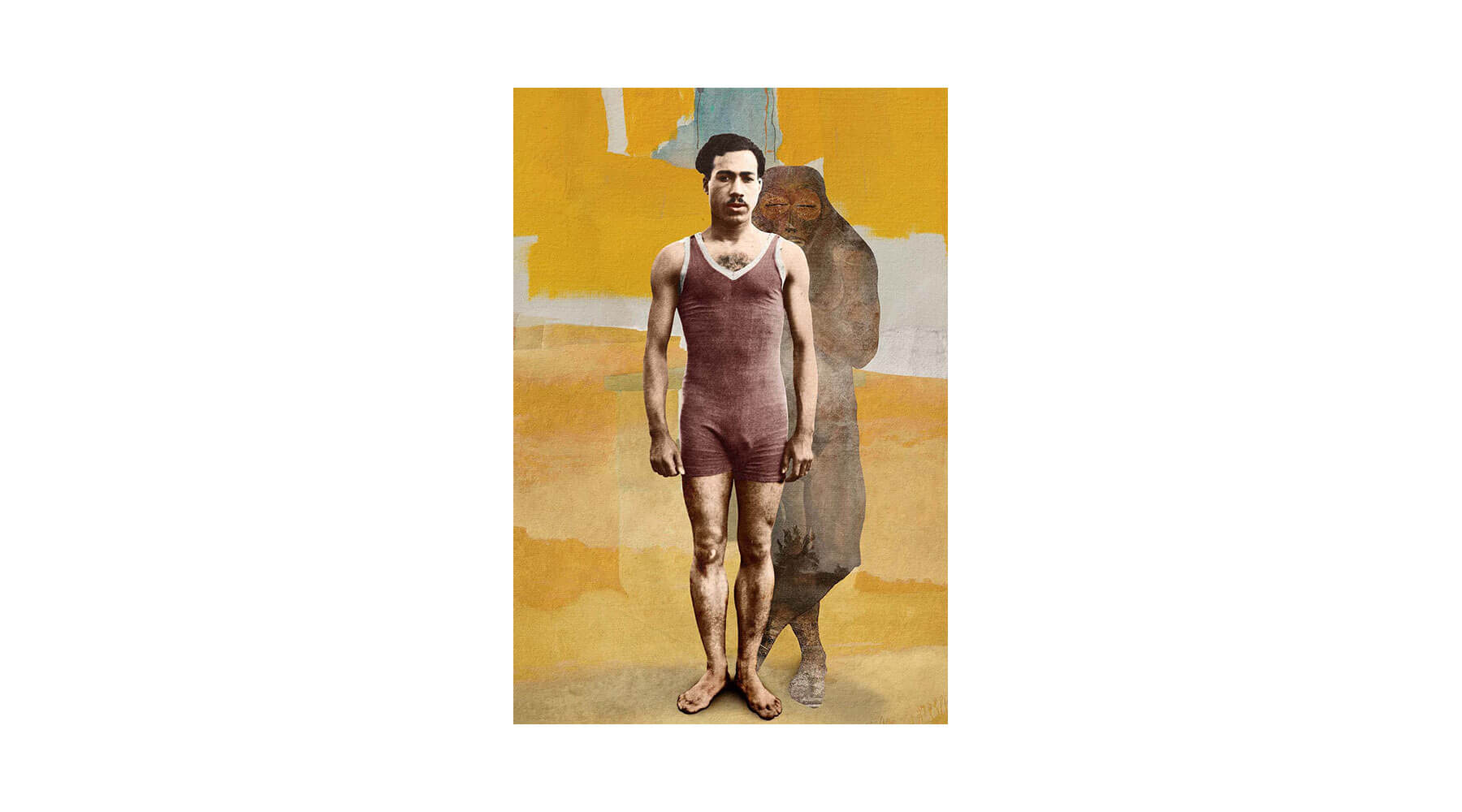

In The Gatekeeper’s Truth, a pensive young man standing on the beach, in full bathing suit common in the 1920s and 1930s, is shadowed by a foreboding dark figure just behind his shoulder. This shadow creature is an ominous presence, a combination of mythical references from African masks to Greek mythology.

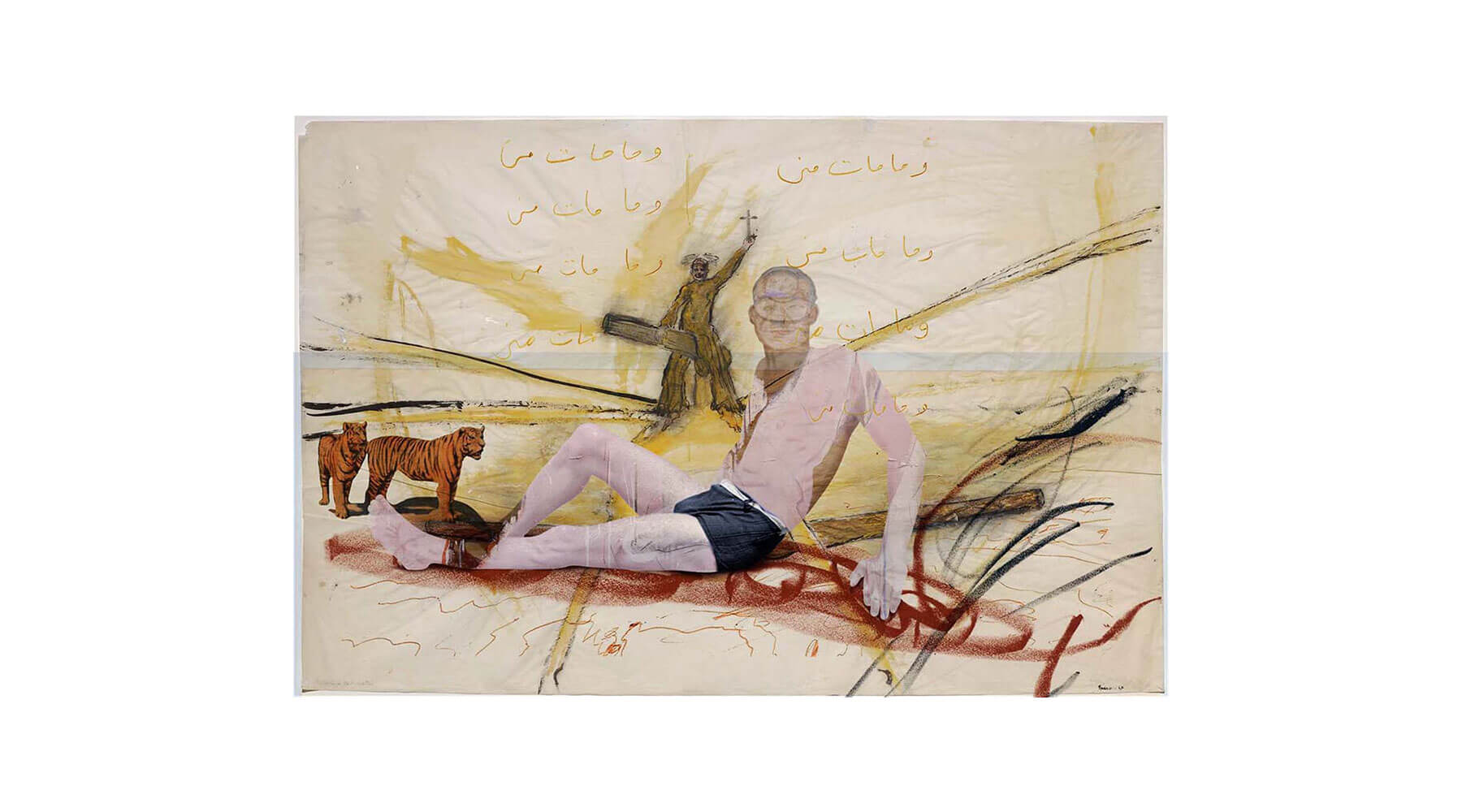

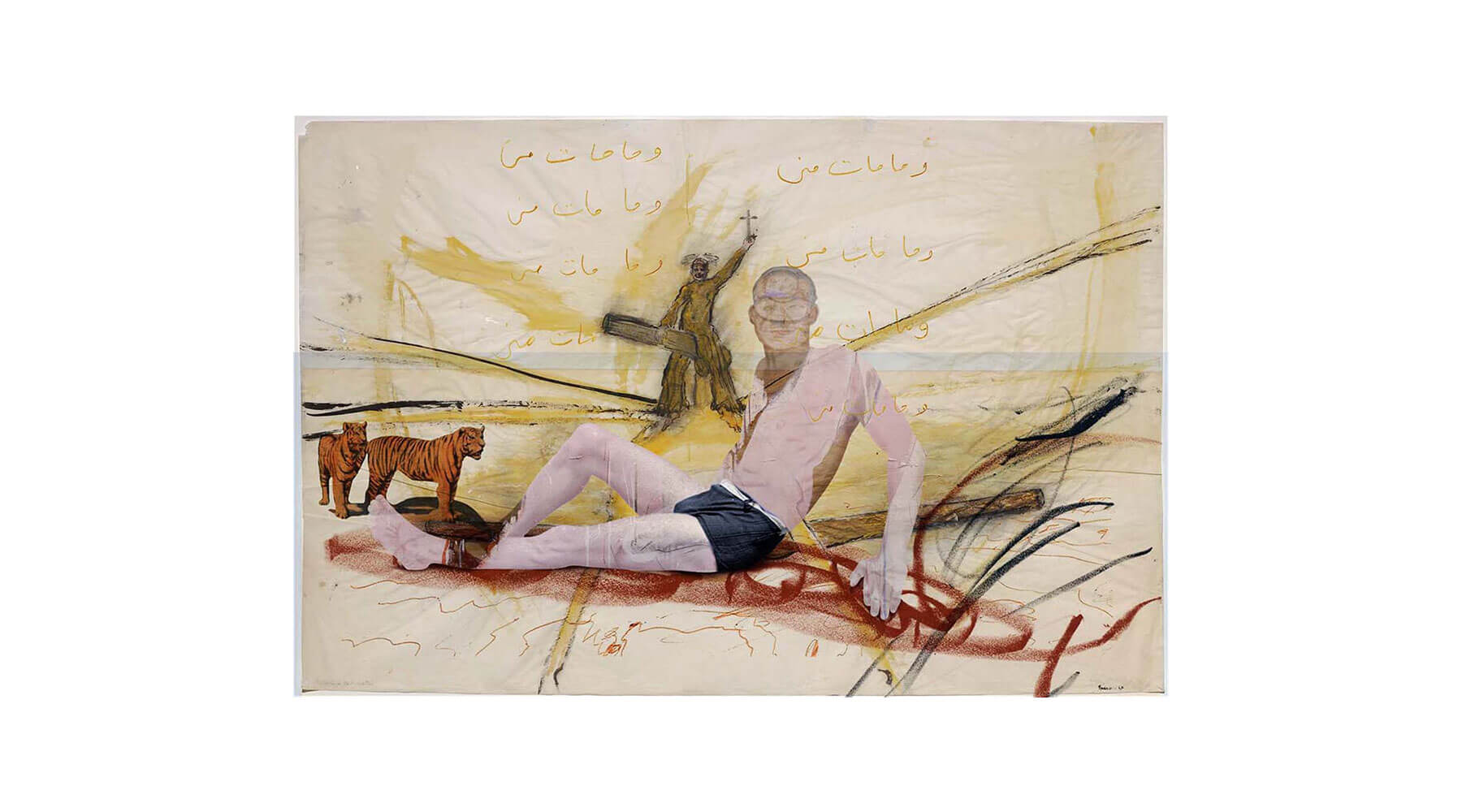

As with other images in this series, the works act as totems, or sacred objects, imbued with esoteric references. Accordingly, the second half of the series appears more fluid, a dispersed echo of the first eleven works, more loosely referenced to archetypal characteristics, a less self-conscious approach, Hammam allowing us into her thought process without worrying what it may reveal. Printed on fine, translucent Japanese photo paper the work is light and delicate, acting as a reminder of the ephemerality of memory and the fragility of time. She sees these works as part memoir and part an illustration of the subconscious. If left to continue working on them, the works would continue to transform, acting as open-ended questions.

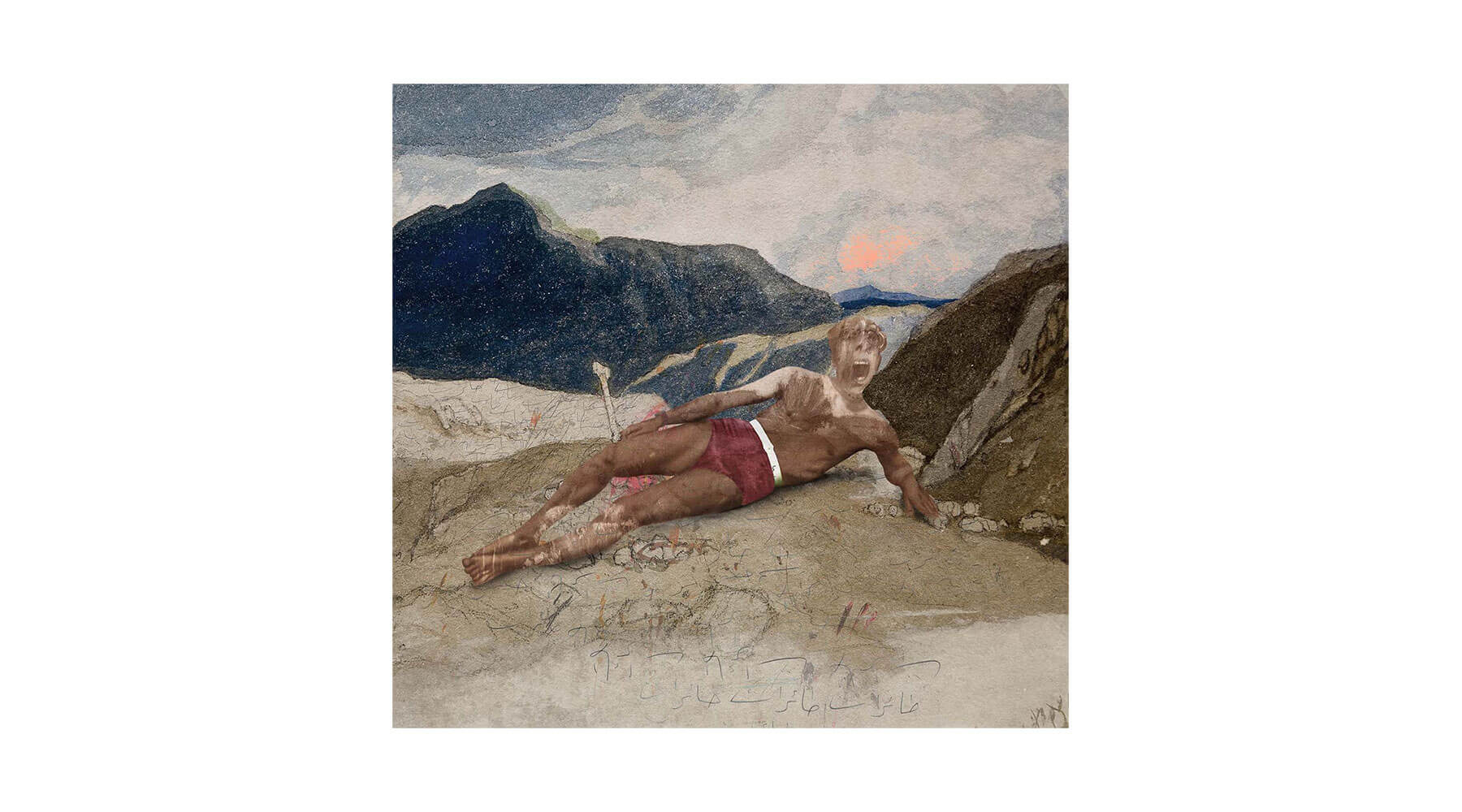

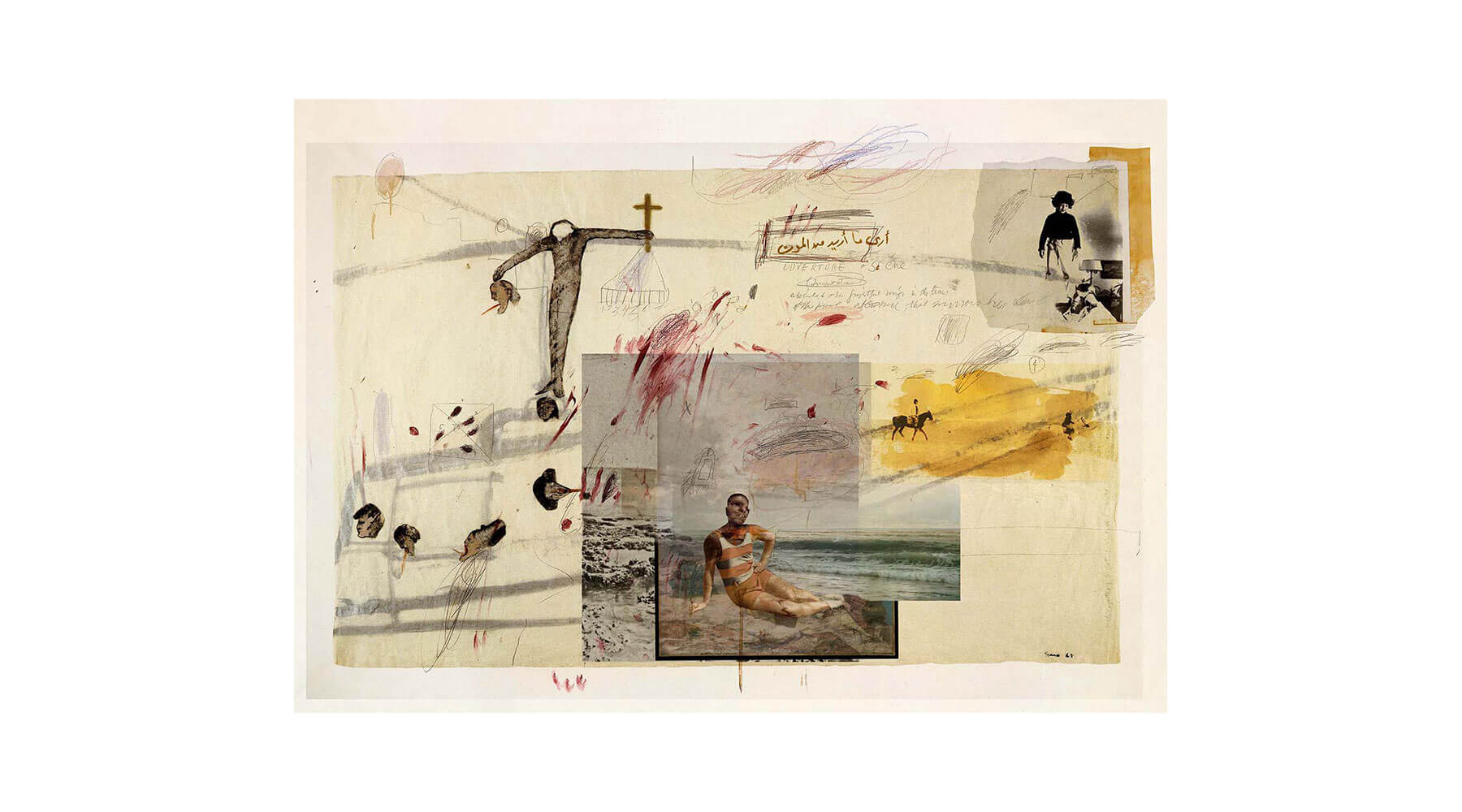

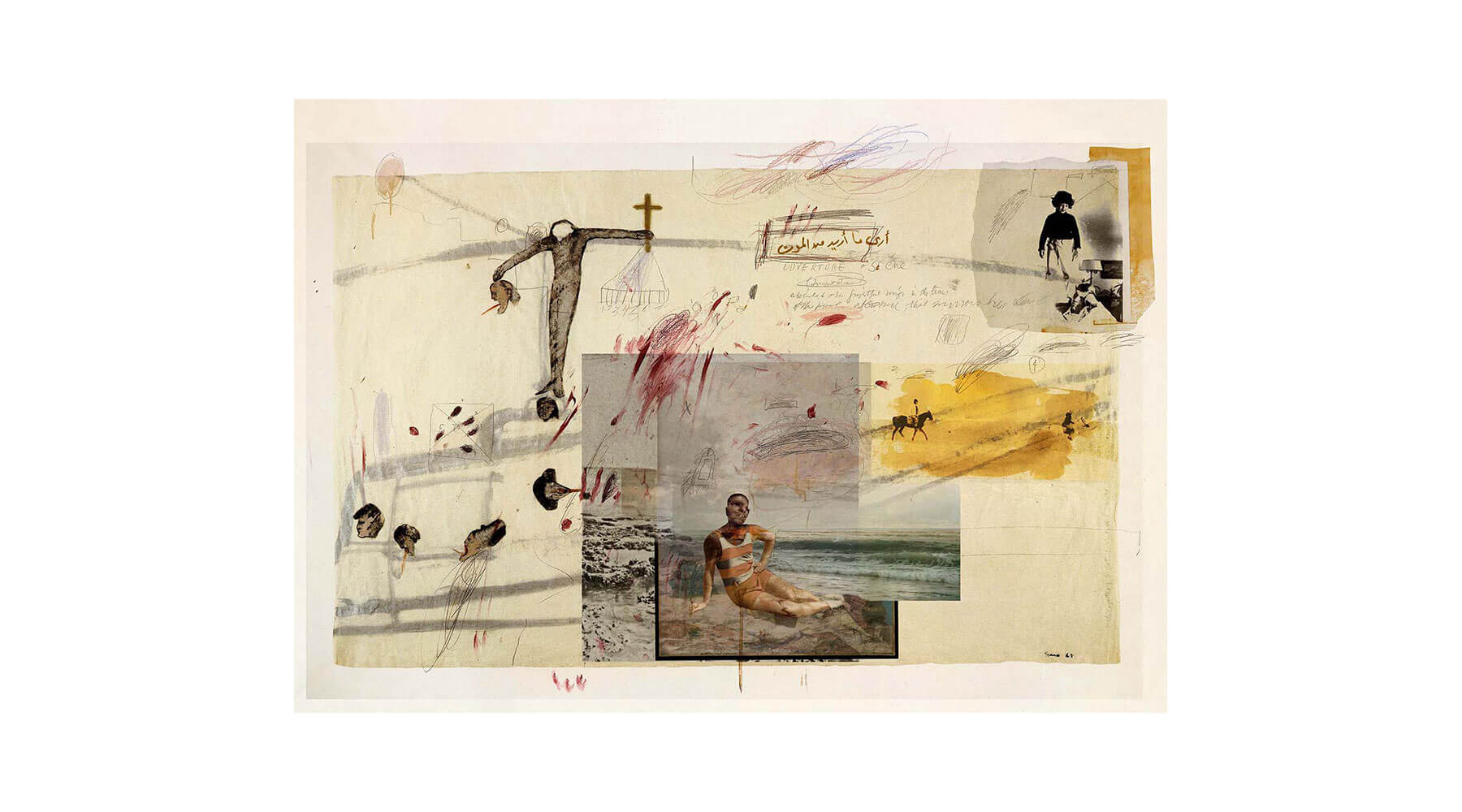

In Narcissus Drowning, a man reclines clumsily against dark choppy waters while figures rising from the dead emerge from the shore. As in a dream, familiar figures make appearances–Hammam as a child riding a horse, nude men riding bareback through a neo-baroque landscape, Basquiat’s bull, a recurrent theme in his own work drawing from African tribal masks–facing us unashamedly. A scrawling handwritten text in Arabic reads ‘I gifted you my memory’, referring to the poems by Mahmoud Darwich, the renowned Palestinian writer and thinker, that appear in several other works in this series.

Posturing Bravado shows us a man posing vainly on a rocky shore unaware that his face has been distorted while decapitated heads fall to the ground on his right. In a corner Hammam, as a child again, bravely balances above her father, trying to capture his attention while he looks away. Grey charcoal-like lines work their way across the paper, under the visible layer, trying to connect and make sense of the different layers of images, their associations and what they may represent.

Alexandria has always held a mythical place in many artists’ and writers’ imagination and for Hammam no less. Spending her summers there as a child she experienced Alexandria as a paradise already imbued with the stories of an even greater past, handed down through earlier generations.

In A’aru we see the artist negotiate that burden of memory and what she sees as the shared guilt of the ruination of a place. Place here not only being Alexandria, but the world at large; her work a critique of short sighted, global, rapid over development without much thought to nature or the environment. These totemic works are imbued with references to the shamanic, the archetypal, the unconscious drives, aspirations and struggles within the collective self. Like maps, they are visual canvases where Hammam conjures up a magical space in which a collective transformation could be possible for the artist, and for us, offering to guide us through the difficult journey to a potential A’aru.

Zein Khalifa and Heba Farid

Co-founders